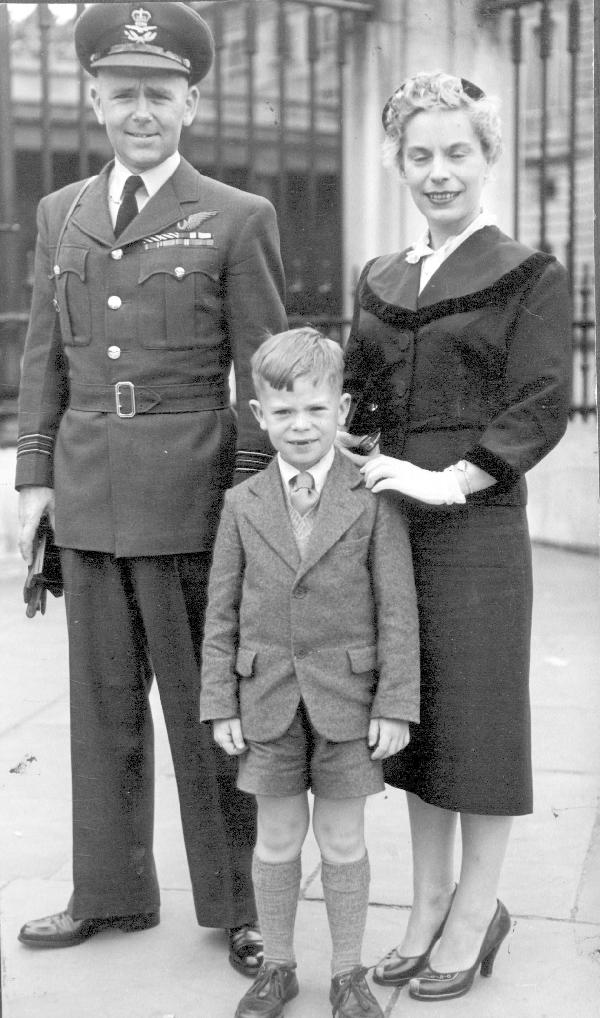

For the rest of 1956 we lived in Sutton whilst I took the Flying College Course at RAF Manby. There was a pleasant interruption on 24th July when I was required at Buckingham Palace to attend an Investiture by the Queen for the AFC; Pat and Peter accompanied me.

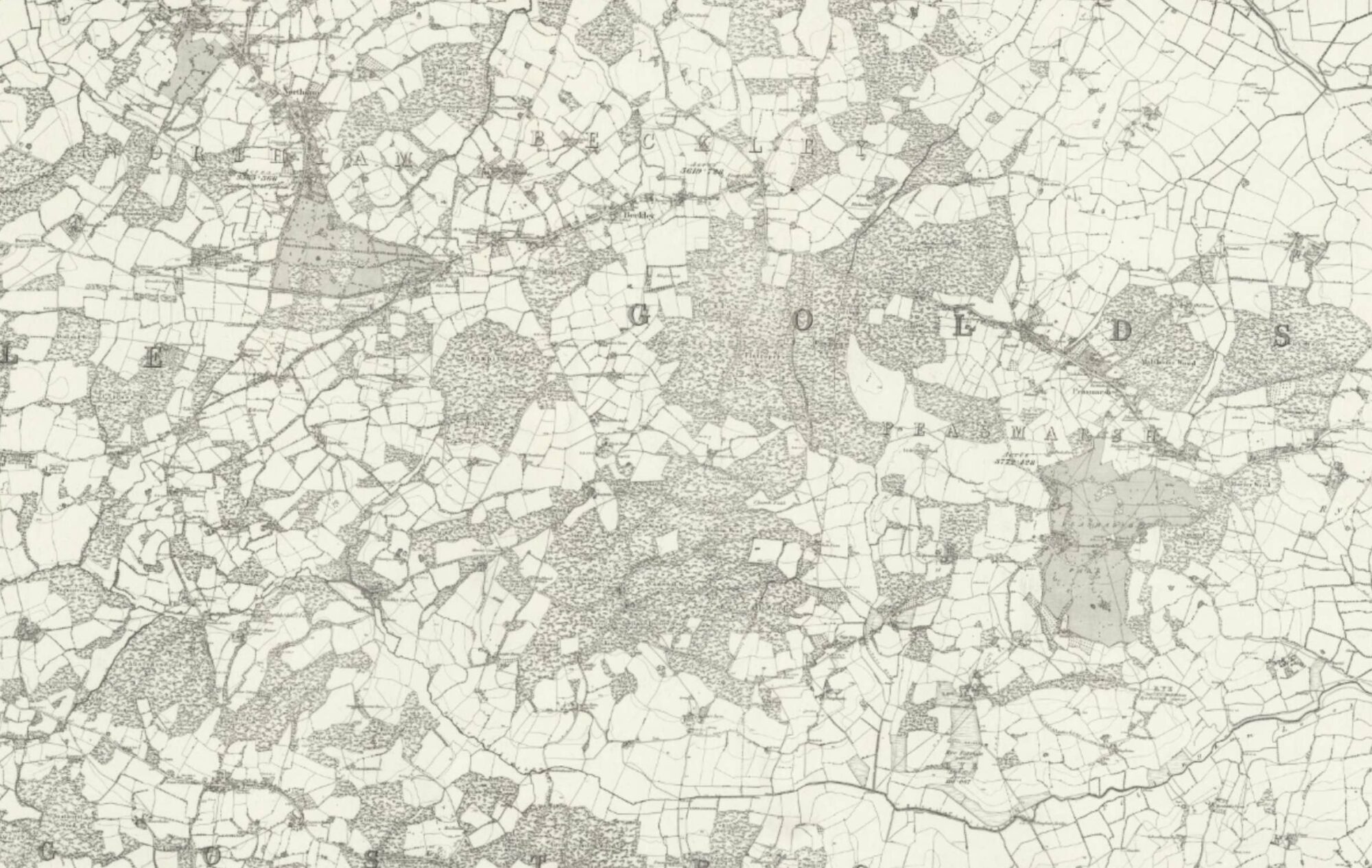

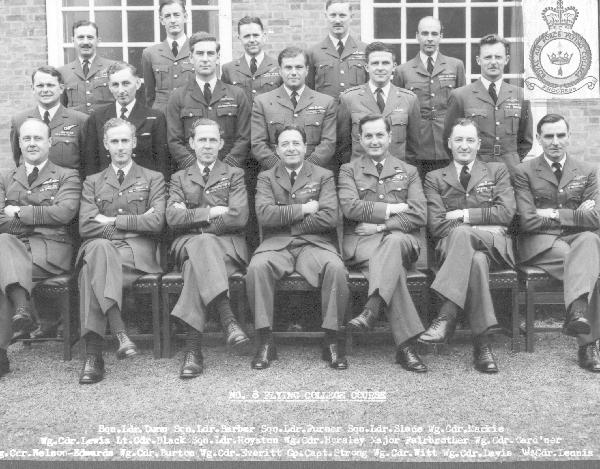

The course was interesting, instructive and good fun. Air Commodore “Gus” Walker (there he is again!) was the Commandant of RAF Manby initially, but he handed over during our time to Air Cdre “Paddy” Dunn. There were 18 of us on the course, 14 pilots and 4 navigators; of the pilots, one was Naval, one Australian and one American. Senior man was Gp Capt Strong who sadly is no longer with us. Other colourful characters were : Sqdn Ldr Royston, the Australian, whom I was to meet some years later in Canberra; and four splendid Wg Cdrs—Denis Witt, Harry Burton, Hugh Everitt and Peter Horsley—all of whom went on to higher things; the last, Peter Horsley, took sadistic pleasure in throwing me around in a Meteor after I’d done his Maths for him in the classroom. We visited aeronautical Companies, we entertained a Soviet Air Force Delegation and we journeyed to the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) to see at first hand part of the “trip wire” in cold-war Europe. I remember our return to Manby from that trip: it was a Sunday and a Customs Officer from Grimsby had to meet us. Whether he was unhappy about being called out on a Sunday, or whether he was just not in the mood, the fact was that he clobbered us for everything. Each of us had brought back just 1 bottle of spirits and 200 cigarettes and he charged duty on the lot. “It’s only a privilege, you know”, he said; and that day he wasn’t in the mood to provide the usual privilege. So we let down the tyres of his van.

Apart from classroom work, I flew 44 times with 20 different pilots on 5 types of aircraft, principally the Lincoln (stretched Lancaster) and the Canberra, the first of our jet bombers (a few still flying today). As a byproduct, it was exciting for a mere navigator to take the controls of a Meteor. We studied all current air power tactics and of course, since the West and the East were now very edgy in a Cold War environment, we went into significant detail of the nuclear question and the subject of deterrence.

Now that I’m back in my own country, I think it’s timely to put down a few thoughts on where we stood on the international scene in 1956. The euphoria that existed in May 1945 with Victory in Europe and the three “U”s clasping hands—USA, UK and USSR—had soon evaporated with Stalin’s sinister and cynical policy of taking over the whole of the eastern half of Europe into the rigid yet economically inefficient grip of Communism. The USA meanwhile had poured billions of dollars in aid and loans to western Europe under the Marshall Plan, which Churchill described as “one of the most unsordid acts in history”. Churchill himself had spoken bluntly in Fulton, Missouri, about the “iron curtain” descending between the west and the east. The west had rapidly demobilised soon after WWII; the USSR had not. Stalin had attempted to force the western powers out of West Berlin, which formed an enclave of comparative freedom within what had become communist East Germany; he failed because of the determined efforts of the USAF and the RAF to keep West Berlin supplied; he backed down. In 1949 twelve nations had come together to form a purely defensive alliance: they called it NATO—the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. (In French it had to be OTAN of course). Those twelve were—Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. The most important Article of their Treaty was NATO’s raison d’etre: Article 5 stated “The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all …” The inevitable response by Stalin to this organisation was the establishment of the “Warsaw Pact”, joining together in a similar framework the USSR and all the dozen communist regimes. The Cold War had set in. A mere six years later it was to affect me personally in a near “Dr Strangelove” scenario.

A fundamental backdrop to the Cold War—and the principal reason why it never switched to Hot—was the Nuclear Deterrent Forces on both sides. Stalin always used to say that the USA was out to destroy him, but the USA did nothing with its few years of nuclear advantage. The USA was first in nuclear production (thank goodness it wasn’t Hitler!), then the UK, then in rapid succession France and the USSR. Once the USSR had started on the nuclear path, their development and deployment were rapid. Both sides increasingly stockpiled long-range bombers, missiles and nuclear warheads. In these circumstances, it was particularly poignant on 6th September 1956 that we should have a Guest Night at RAF Manby in honour of a visit by the Soviet Air Force Delegation at which Air Chief Marshal P F Zhigarev proposed the toast to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and the Commandant followed with the toast to The Chairman of the Praesidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics. (Yes, one needed all those words to describe the formal title of Stalin’s successor, Khrushchev).

As far as the United Kingdom was concerned, the nuclear deterrent was to be based in Bomber Command with three different 4-jet aircraft—the Valiant, Vulcan and Victor, appearing in that order. The overall title was inevitably the V-Force. I had seen prototypes in my Boscombe Down days. The Valiant was very much now in the front line; the others were awaited. It is interesting to look back and record that it was the post-war Labour Government under Clement Attlee which took the brave step of establishing the programme for the V-Bombers and the nuclear weaponry which they would carry. However, it was at this point in history (autumn 1956) when the United Kingdom’s foreign and defence policy took a somewhat bizarre turn. We were doing very well in divesting ourselves of the former British Empire—indeed, it would be difficult to find in history a handing over of control and responsibility that was more benign and better planned. But Anthony Eden, the then Conservative Prime Minister, felt very sore about the Egyptian President Nasser’s “seizure” of the Suez Canal and, in cynical collusion with the French and the Israelis, started a war to punish Nasser and to regain the Canal. The Army was sent in on the ground and the brand-new Valiant bombers were dispatched to target Egyptian airfields with conventional bombs; there was said to be some muttering amongst aircrews who had been deployed to Cyprus and were unhappy about the task. The USA, with the full prestige of President Eisenhower, who had been the first SACEUR, did not approve. We all withdrew, tails between our legs, Eden shamed and finished. Watching all this from the sidelines at RAF Manby, most of us were pretty horrified.

I was still a Squadron Leader at the end of the course and hence was posted to another Sqdn Ldr appointment. In January 1957 I had to report to Air Ministry to work in the Directorate of Operational Requirements—that is, to progress new equipments through the factories and into Service; committees, conferences, visits to Companies, writing papers, a bit of flying (just 16 flights in the short time there, mainly just to keep one’s hand in). It provided a widening of experience, particularly in dealing with aviation companies. But it wasn’t to last very long. Promotion lists appear every 1st January and 1st July. I appeared on the 1st July 1957 list: I therefore had to be moved—to a Wing Commander post; and I began to suspect some manouevrings by “Gus” Walker who, as an Air Vice-Marshal, was now Air Officer Commanding No 1 Group (Bomber Command) at Bawtry, Yorkshire and was busy building up the second part of the V-Force, the Vulcans. They posted me to RAF Waddington, the first Vulcan station, as OC Operations Wing. I was thrilled.

But before we get going to Waddington, let me tell you about our domestic arrangements whilst I was working at the Air Ministry. We lived in a hiring—53 Dahlia Gardens, Mitcham (home No 13) and I used to travel up to Whitehall by bus and rail. Pat, bless her, quickly settled in to her new surroundings. Peter, now 8, attended at Sherwood School: the School was badly led by a hopeless Headmistress and the six months or so there was a waste of time. Once again, Peter’s education was a very serious worry; it couldn’t go on like this much longer. Richard was 2 and great company for Pat.

Oh—and I must mention that I took part in a cricket match just before leaving the Ministry. The programme read: “On ye tenth day of ye seventh month 1957 a cricket tournament shall be held betwix ye Valiant Knights of Weybridge, their Captain Sir George Edwards … and ye Winged Knights of ye Directorate of Operational Requirements, their Captain Air Cdre J Roulston.” Sir George Edwards, you see, ran Vickers who built the Valiant. I scored 2, run out; I was wearing plimsolls and the grass was wet. Son Peter has for ever been ashamed of me for that.

Farewell, then, to Whitehall, with no tears. On, on towards RAF Waddington; but not immediately. The powers that be had decided that I should have a flying refresher on Canberras—at Wittering, next to the Great North Road—seemingly unaware of all the aircraft types that were still fresh in my mind from Dayton. I dutifully turned up at Wittering and sat down at a desk in a classroom. On the desk was a cable from the AVM himself, “Gus”, saying simply –“Forget it, leave Wittering, go straight to Waddington.” I was pleased about that. So further north I went, to RAF Waddington, a few miles south of the City of Lincoln. I reported to the Station Commander, Gp Capt Ring, as his first OC Ops Wing. I knew immediately that we were going to get on fine. He told me that the same powers-that-be had stipulated that I should first go through a Vulcan conversion course with the OCU (Operational Conversion Unit) but he figured I should scrub that too and just get on with the job. So that was how it was to be. I was a V-Force Wing Cdr Ops right from the start. Great.

Before I tell you more details about the job, let’s catch up on the domestic scene. For some reason—I seem to remember that the maintenance people were refurbishing the Wing Cdr Ops’ quarter—when Pat and the boys arrived we had to go first into a temporary quarter away from the central square (sounds familiar, doesn’t it?). It was 19 Tedder Drive (home No 14) and we were there only a few months. When it became ready we moved into No 5 Trenchard Square (home No 15) which, compared with all our previous homes, was pretty palatial. I had to insist that they widen the garage doors in order to get the Chevvy in (mutterings from the Clerk of Works—“b—-—great American cars”). Actually the previous structure wouldn’t let in anything bigger than a mini. On the airfield I drove a jeep.

Dear Pat, once again, responded swiftly and uncomplainingly to the task of settling in to the home we would now have for nearly two and a half years. It sported an enormous Aga in the kitchen and we both came to understand what an extraordinary piece of gear it was. I just about had enough spare funds to invest for the first time in a stereo Hi-Fi setup (well, medium-Fi) with

Decca tweeters up in the corner of the walls; there was the absurd thrill of having trains pass through our living room. Our neighbours around the Square were: the Station Commander Gp Capt Spencer “Ting” Ring and Peggy; Wg Cdr Admin Peter Matthews and Eve; OC 83 Sqdn Wg Cdr “Syd” Banks and Gloria; and OC Vulcan OCU Wg Cdr Frank Dodd and Joyce; and behind us, with adjoining gardens, OC Eng Wing Wg Cdr Maurice Hermiston and Anne. All of them very good at their jobs and very nice people.

As to the boys—well, Peter started at a local school (Bracebridge Heath) on the outskirts of Lincoln, but I had a chat with the Headmaster and, after hearing of Peter’s schooling up to that point, he strongly advised us to send him to board in Stamford School, about 40 miles south on the A1. This was a very difficult decision. On the one hand, Peter had to have continuity from now on. He had passed swiftly through 5 different schools of varying standards and was still only 9 years old. On the other hand, it seemed very early to separate him from the family. Fortunately the distance away was short: we were only an hour away in any emergency. Certainly Stamford had a good reputation. We decided therefore to apply for him to enter Stamford in January 1958. The early days and weeks were sad for him, and for us—but in his interests that is the way it had to be. He was to remain at Stamford until completing his “A” Levels. Some years later when going away to board had become second nature to him, he remarked to Pat and me that, however he felt whilst away at school, it was made all worth-while by the pleasure of coming home in the holidays; well said. Because of our gypsy-like existence, the Air Ministry did subsidise the school fees to some extent. Richard, at 3 years old by March 1958, entered the nursery school at RAF Waddington.

Now—to work. Waddington had been chosen as the first Vulcan base. At first, during my time there, it was in the build-up stage and it housed No 230 Operational Conversion Unit (OCU) and the first Squadron No 83, each commanded by a Wing Commander. The Station employed three more Wg Cdrs—Operations, Engineering and Administration, the usual three prongs. All five Wg Cdrs were directly responsible to the Station Commander. All crews destined for later Vulcan squadrons—and there would eventually be 9 such squadrons of 8 aircraft each—were to be converted to the Vulcan by a short course in the OCU. The aircraft, which cost £1,000,000 each (in 1957 money!), were extremely complex machines and demanded a wide range of experts to keep them maintained. In effect, RAF Waddington was a small town capable of producing its own electricity, water and other domestic supplies and accommodating and feeding many hundreds of service personnel and their families.

The Operations Wing, which I commanded, provided all the facilities required to operate the aircraft. Within it, the Flying Support Squadron manned the Operations Headquarters which included such sections as Navigation, Flight Planning (Peace), Flight Planning (War), Signals, Air Electronics and Flying Clothing. Air Traffic Control guided the aircraft in their movements on or near the airfield and assisted them in bad weather by many various radar and radio aids, to land safely; and was responsible for any action required in the event of an emergency and maintained a fleet of crash vehicles for this purpose. The Meteorological Section provided information on current and future weather for the aircrews. My office, of course, was in the Operations Headquarters. Wg Cdr Engineering was responsible elsewhere on the Station for the efficient maintenance of the aircraft and equipment; Wg Cdr Administration resided in Station Headquarters alongside the Station Commander. I mention that last because, by the time I returned to a similar station 10 years later, the emphasis had changed: the Station Commander’s office was in Operations Headquarters.

The Vulcan was a formidable weapon system. It was the largest delta wing aircraft in the world. It was built by AVRO whose name had been made legendary by the WWII Lancaster. A total of 136 Vulcans would be built before the production line stopped. The Vulcan was powered by four Bristol Olympus turbojet engines. The crew comprised five officers: two pilots (captain and co-pilot), two navigators (nav-plotter and nav-radar) and an air electronics officer (AEO). There were fascinating statistics about the aircraft’s structure: the sheet metal on it would cover one and a half football pitches; it had 14 miles of electric cables, two miles of tubing, 167,000 parts, excluding the engines, and hundreds of thousands of nuts, bolts, washers and rivets. It was fitted with power-operated controls incorporating artificial “feel” and all control surfaces and operating systems were duplicated in case of failure. It had an undercarriage comprising 18 wheels controlled by hydraulic power, which also drove bomb doors and a steerable nose-wheel. Four generators produced the electricity required by the 102 electric motors which operated the various moving parts and drove the many electronic devices. Enough power was generated to supply the normal requirements of a row of thirty houses. A braking parachute was carried in the tail to slow the aircraft after landing, in order to minimise brake wear. (Another job for somebody after every flight—repacking the ’chute!)

On the negative side, there were initial troubles with the aircraft’s power supplies which caused two crews to lose their lives.

The Vulcan flew at 0.9 Mach. It would climb quickly to 40,000 feet and then more slowly (“cruise climb”) for fuel economy to 50,000. Despite its size and bulk, it flew almost like a fighter. The navigators and AEO sat at a bench across the width of the cabin, facing aft, behind and below the two pilots. The nav-plotter was keeping the log and chart of the flight, operating all the navigation equipment except the H2S radar, that is, compasses, Doppler, Air and Ground Position Indicators. The nav-radar operated the H2S—now a Mark 9 with much enhanced 3-centimetre wavelength and ten inch diameter scope—and he would become the bombaimer in a rehearsal or—God forbid—real situation. The AEO had a battery of electronic counter-measure equipments to monitor and activate. Most flights were training flights of one type or another; some were destined for overseas bases to “show the flag”; many took place in the eastern part of Canada to practise low-level flying. The bomb-load could be a number of conventional weapons or the British nuclear weapon.

All the V-aircraft were designed to carry the thermonuclear weapon—the so-called hydrogen bomb, which had undergone testing at Christmas Island earlier in 1957. The word deterrent appeared more and more in the military vocabulary. We in the V-Force were all part of the British independent nuclear deterrent; it stayed with the RAF until, years later, the Royal Navy took over the task with submarines carrying Polaris. For the first time in history, awesome weapons systems existed whose primary purpose was not to wage war but to prevent it. In order for the deterrent capability to be credible exercises were held from to time to bring all aircraft on the station to short-term readiness and for any 4 Vulcans to launch in the air within 4 minutes, that being the minimum warning time of the approach of a ballistic missile. In periods of international tension it was planned that small units of 4 aircraft would fly off to dispersal airfields; Waddington and other V-Force stations eventually had 5 dispersal airfields each to liaise with and to keep stocked.

There were—and still are—many well-meaning people who questioned the theory of nuclear deterrence. They assembled particularly in the organisation known as CND—the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. There was a period in the late 50s and the 60s when marches took place to Aldermaston (where nuclear weapons were constructed) to protest against nuclear weapons and calling for their dismantlement. I sincerely feel they were wrong. In all of history up to 1945, no weapon had been produced which deterred war, which stayed politicians’ hands. The nuclear weapon was of a completely different order, and remember we are talking now not of the single 20 Kiloton weapon which devastated Hiroshima in 1945, but a weapon at least 50 times as powerful. All responsible leaders are well aware that the unleashing of such power will not only fail to achieve a war aim, but indeed may well signal the end of civilised society. By the late 1950s, the time we are now in at RAF Waddington, a balance was building up between the West and the East in nuclear power. Each deterred the other. Destroy all those nuclear weapons (and who is going to be sure it’s done?) and you remove the deterrent; you remove the fear of mutual suicide; you thus create the situation existing before 1939, when politicians might well be prepared again to take risks and cause major war to begin. Once it has begun, there is nothing to stop the production of nuclear weapons all over again and their use by one or both of the warring nations. For instance, in pre-1939 terms, the Berlin problem in 1948/49 could well have brought about a major war. In sum, I have no doubt whatever that nuclear weapons are here to stay and it is right that Britain should be a nuclear nation. All British Governments—both left and right—have subscribed strongly to that view, even after manifestos might have sounded doubts. Once in power, Governments listen carefully to Intelligence briefings.

Of course, there are irresponsible leaders. There are hotheads in Iraq, Iran, Libya, North Korea, etc., who may not feel so sensitive about general chaos around them. One can only trust that the more responsible Intelligence services—USA, NATO, Russia, Israel for instance—are able to keep tabs on their wild adventures and be prepared to take out mass-destructive capabilities before they mature.

Now let me return to Waddington activities. First of all, my own flying: whilst at Waddington, I flew 57 times, mostly in 11 different Vulcans, with 18 different pilots, including two Station Commanders, and the Squadron and OCU commanders; I flew in the roles of nav-plotter, nav-radar and co-pilot.

Apart from the routine task of commanding the Operations Wing, there were a number of events outside the normal run. I suppose the most memorable of these was an invitation the Royal Air Force received in June 1958 from the Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia to attend their Centennial Celebration. Two Vulcans were sent to represent the RAF; this would be one of the first occasions when the Vulcan was seen in the air by an audience overseas. The Force Commander was none other than our AOC No 1 Group—AVM “Gus” Walker—and I was nominated as his Deputy Force Commander. There was a nice coincidence here—both the AVM and I had Southend connections; so the PR people put out a press release to appear in the local Southend newspaper. His address was given as Canewdon Road, Westcliff and mine as Apton Hall Road, Canewdon, where my mother and step-father were living at the time. The two captains selected were Sqdn Ldr Freddie Staff and Flt Lt Price. In Vancouver we gave a couple of displays with the two aircraft and I’m afraid I had an argument—perhaps ill-advised, who knows—with the great “Gus”. He was anxious to honour a promise to display over a small grass airfield at Abbotsford that he had made to the local branch of ex-RCAF types; at exactly the same time there was a prestigious Air Pageant at the big military airfield (Sea Island) at which American and Russian aircraft, amongst others, were taking part and which expected a crowd totalling anything up to 50,000; I was trying to persuade him, somewhat forcefully, to switch from the small crowd to the large. He wouldn’t budge. So on that particular afternoon we displayed over a crowd of about 100 instead of the 50,000. Since we were based at the military airfield during our stay there, it was bizarre that we deserted the Air Pageant laid on specifically for the Centennial. Whilst at that airfield I was able to take a short familiarisation flight in the prototype Boeing 707 which had not yet entered airline service; and to examine the interior of a visiting Russian Tupolev 104, which was quaint with a Victorian type of internal décor.

“Gus” shamed us all by coping immediately with one arm in a session of water skiing; the rest of us at the first attempt floundered with half the body below the water. The Canadians were immensely hospitable and I soon forgot the argument between Force Commander and Deputy. Before I left Vancouver I was handed a newspaper front page entitled the Frontier Ghost Town Gazette; the bold 1 inch headline read “Wg Cdr Furner gets acquitted as horse thief”. To finish an exciting week, I flew in one of the Vulcans home which had been briefed to fly from Ottawa to overhead Heathrow in an attempt to break the then speed record. We did so, clocking up 5 hours 45 minutes.

I recall that the Lincolnshire winters were generally pretty chilly. One such—that of 1958/59—produced some really foul conditions for a couple of weeks. A lot of snow, ice, and fog. One morning I set out in my jeep in thick fog to travel round the perimeter track with a view to checking the state of the runway. Unfortunately, I was not mindful of left or right of the track and all of a sudden I went smack into another Jeep coming the other way, driven by an airman—who was blameless; mea culpa. We were both a bit shaken but nothing broken; the two Jeeps were in a sorry state. There was a Court of Inquiry chaired by OC 83, “Syd” Banks, who put it all down to “excessive zeal” on the part of the Wg Cdr Ops. I was sent for by the AOC—“Gus”—who sat me down, had a long chat about most other things and apologised for charging me £20 towards the cost of the damage. Much more seriously there was an incident one day involving a Vulcan returning from an overseas trip after a long flight. There had been a lot of recent snow. The runway was not completely cleared. A bank of it lay down the length of the runway near to the left hand edge, but not completely off the runway. The pilot had been warned repeatedly that the bank existed and to bias his approach to the right of centre. As his speed on the runway reduced, he veered very slightly to the left and hit the bank of snow. The Vulcan was badly damaged; the crew were unhurt.

Our Wg Cdr Eng (Maurice Hermiston—“Hermy”) was bubbling with ideas about this and that and I recall that he had a minor brainstorm to combat snow and ice on the runway. Two miles long and a hundred yards wide carries a lot of snow and ice and bowsers fitted with blades spend an awfully long time pushing snow one way or the other, gradually building up bigger and bigger banks. Hermy constructed, in true Heath Robinson style, a contraption fired by an old jet engine removed from a Vampire, with the resulting hot blast fanned out by a network of pipes. We had to be careful that the angle was right: we didn’t want to burn up the tarmac. And of course there was often the problem of the resulting water freezing behind us. Let’s say, it helped. On another occasion, in order to cater for a belly landing (undercarriage problem) he put together another very large contraption for spreading foam across at least half of the runway width. I don’t seem to remember that he patented either idea.

Since Waddington was the home of the first Vulcans (the second Squadron went to Finningley and the third to Scampton, then the fourth to Waddington, and so on) the Station was host to many visitors, some from foreign countries and some accompanied by our AOC—“Gus”. We had a set pattern for this sort of thing: escorting to the various sections with briefers at the ready in each, a lunch in the Mess, and the piece de resistance in the afternoon, a 4-Vulcan scramble from the firing of a flare and an individual aircraft display. With its enormous triangular shape, the Vulcan was without doubt one of the most impressive aircraft in the world. The AOC also visited us as a matter of annual formality for “AOC’s Inspection”. For weeks the watchword would have been “If it moves, salute it; if it doesn’t, paint it.” In other words, bags of bull. On his arrival, Guard of Honour; then full parade of the Station and inspection—he would remember airmen’s names from his previous visits; then a tour around most sections of the Station and he would be bubbling with everybody he met and make them all feel they were important and indispensable.

For two years running, in September of 1958 and 1959, around about Battle of Britain time, I had to organise the Station and the airfield for an “At Home” day when thousands of visitors poured in and the afternoon was taken up with a very busy flying display. And I mean busy. My team and I arranged for aircraft to arrive over the airfield for display with only a minute between them. Timing was vital. All went well on both occasions, except for one error. An American pilot of an RB66 got ready to display at RAF Swinderby a few miles from Waddington and was mystified by the lack of interest there. Our Air Traffic Control people caught up with him and gave him a steer to Waddington and he arrived slap in the middle of a very energetic Meteor display—in fact the RB66 went straight through a Meteor loop, which wasn’t in the programme but looked very impressive. The hit of each event, of course, was the multi-decibel pull away from the crowd at a terrific angle by the Vulcan on full throttle. Not the least of our concerns on these At Home days were the erection of WC facilities and clearing up the rubbish afterwards: once a year was enough!

Another memorable event was the granting to the Station on 25th April 1959 of the Honorary Freedom of the City of Lincoln. Three years before the City Council had given permission for the City crest to be inscribed on the fuselage of all Waddington based aircraft. Thus the crest had been carried by Vulcans to many countries of the world, including the Middle East, Turkey, Africa, India, Malaya, Phillipines and North and South Americas. Now, on this day, a contingent from the Station marched through the City, we attended a formal ceremony for the presentation of the Freedom and invited the Mayor, Sheriff, Aldermen and prominent citizens back to the Mess and subsequently to our Quarters. The write-up on the event included the statement that “Ermine Street, which many centuries ago echoed to the tramp of Roman Legions, now reverberates to the roar of Olympus engines”—which, you must admit, is a fascinating link.

I’ve mentioned the Officers’ Mess a couple of times. Almost from the day of my arrival, and throughout my whole tour at Waddington, both “Ting” Ring and his successor as Station Commander, Gp Capt “Hank” Iveson, thought it would be a good thing if I had the secondary duty of PMC—President of the Mess Committee, in effect responsible for the policy and running of the Officers’ Mess. Thus it was that Pat and I had to be present at every event that was happening in the Mess, with the inevitable effect on one’s Mess bill (which by the way never turned up at dawn on the 1st—I couldn’t educate the Mess Secretary to that pitch of excellence) and on baby-sitting arrangements. It meant that I would be in on the detailed planning of a Ball, of every Guest Night and Dining-In Night and every visiting occasion. There was one evening of a Formal Ball when we organised an elimination dance: the Wg Cdrs acted as the Judges and Pat was one of those who gracefully turned the Judges’ choices off the floor. Pat was instructed to turn off the sister of Gloria Banks, who like Gloria herself came from Cyprus and was, shall we say, a trifle volatile. She screamed at Pat—how dare she turn Clementine so-and-so off the floor, she who had earned dancing trophies, she who had. etc. You get the picture. Poor Pat was in tears, she had simply been following the Judges’ judgments. Oh dear. At least “Syd” Banks had the courtesy to apologise to Pat later, but the evening had been soured.

The second Station Commander in my time there was a very large jovial man. We flew a lot together. “Hank” Iveson and his wife became good friends of ours and we all kept in touch subsequently. Sadly, neither Ring nor Iveson is now with us.

Towards the end of my time at Waddington, the AOC—“Gus”—moved on to higher things and his successor was AVM Jack (“Iron Jaw”) Davis. I knew little about him except that he was reputed to be a pretty tough cookie as his nickname would seem to indicate. Unfortunately for the AVM, the poor chap was quite ill for a time, particularly through the winter of 1959/60 and was laid up in a hospital bed in Nocton Hall, an RAF Hospital, which happened to be only four miles from the end of our main runway and was therefore lying directly under Waddington’s circuit. I recall one very cold morning when we were still clearing the runway of snow and ice, probably using Hermy’s heat machine, when my phone rang: it was the AOC, from his bed, enquiring as to why he couldn’t hear any aircraft flying yet! I explained the position, said we were doing our best to get the airfield ready and promised him that the day’s flying programme would start very soon. He was still in hospital when I had to leave Waddington on posting and he wrote to me later saying that he was sorry we didn’t have lunch and a chat together before departure—“but I am afraid you slipped away while I was still sick”. Not the neatest of phrases, one might think: still, he thanked me for good work and wished me success in the new post.

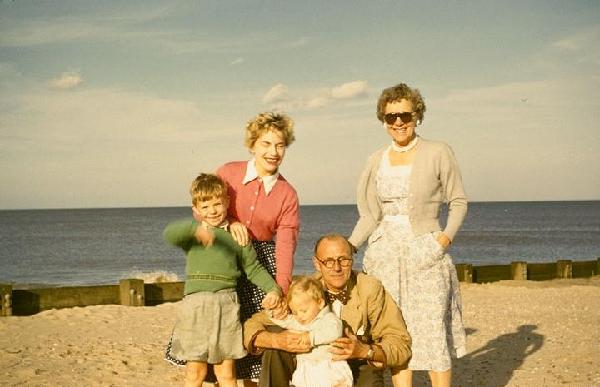

Now what of the family? Pat was absolutely marvellous throughout the whole tour of two and a half years. She had to put up with my trips away, with masses of socialising, some welcome, perhaps a little not so, with many late nights; she was inveigled into a bit of acting; but above all, she was liked and admired by all. The wife of our first Station Commander, Peggy Ring, so admired Pat’s facility for putting people at their ease and for being always the first to break any awkward silence that we were invited to every one of their cocktail parties at which they sought to have every officer on the Station at least once. “But we came to your last one” Pat would say to her. “Ah yes” said Peggy “but we need you at all of them.” Peter by now had reached Form IIIA at Stamford and (I like to think) was settling down there; at least he was only 40 miles away. Richard remained in the Nursery School on the Station until we left. We enjoyed a couple of holidays—not to our full entitlement, I must say—mostly on the Norfolk coast, certainly nothing overseas. My folks and Pat’s folks came to stay with us in Trenchard Square from time to time, and Ken popped in once and joined us at one of the Balls, looking very dashing.

And so it was towards the end of 1959 that I heard what was going to happen next. I was a Wg Cdr of two and a half years seniority and was 38 years old; Charles Ness was earmarked to follow me at Waddington. My next job was to be at High Wycombe, that is, on the Staff of Headquarters Bomber Command, starting in March 1960. When I was “dined out” from the Waddington Mess, they reflected my liking for Tom Lehrer (I had spread him around) with a rendering after dinner of “We’ll all go together when we go”, which they all thought appropriate. In fact, the Cold War had been quiescent as far as the V-Force was concerned during my time at Waddington. But there was going to be an infamous week at High Wycombe when it would rise dangerously in temperature.

There were no Married Quarters readily available in March 1960 at Headquarters Bomber Command. That sounds familiar, doesn’t it?—and a bit weird these days at the turn of the Century when there are so many MQs compared to the demand that they are being sold off by the Ministry of Defence. We had to find a hiring again. Home No 16 was Little Ashenden, Water End, Radnage, Bucks and we were there for three months or so until a Quarter came up in the HQ grounds. There was a tiny village school available (Radnage Primary) and Richard, now just 5, attended. I remember being told one day (the teacher was a neighbour) that Richard had been talking too much and had therefore had to stay in school whilst the rest of the class went out for a nature ramble; he was delighted, all on his own, surrounded by all the school’s books. In the meantime, Peter, now 11, was in Remove A at Stamford; he had just taken an 11+ exam and had done well.

After the initial three months, we moved again, to Home No 17 at 52 Greenwoods, Walters Ash, the address of the larger of two MQ areas at the Headquarters. It was a detached house, more modern but smaller compared with 5 Trenchard at Waddington and it was positioned alongside dozens of other houses which were all the same and equipped with the same furniture. Each of us would have added our own little bits and pieces by this stage of career. Richard changed school again and attended at Naphill School about a mile from the quarter. There was one occasion when his teacher asked whether his father was a navigator: “Oh no”, he said, “he’s just an ordinary chap in the Air Force.” That sort of put-down is good for the soul.

Now let’s get to work. It was a classic case of changing from a large fish in a small pool to a smaller fish in a larger pool. Bomber Command was the major Command under Air Ministry and its HQ was teeming with high-rankers. It had an impressive history. In 1942 during WWII Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris had held sway here until the end of the war; at its peak in January 1945 the Command had 95 Squadrons comprising 2,285 operational aircraft and 193,000 officers, men and women; the C-in-C would order more than 1,000 bombers a night in raids against Germany. After the war he had been snubbed because bombing had been considered in retrospect to be not quite cricket. The Commander-in-Chief when I arrived in the spring of 1960 was Air Marshal Sir Kenneth Cross (known as Bing, a very likeable C-in-C) and he had three AVMs reporting to him: Senior Air Staff Officer (SASO), Air Officer Admin (AOA) and Air Officer Eng (AOE). SASO was, firstly, AVM “Tab” Parselle, a delightful man, and secondly, AVM “Paddy” Menaul, a horse of a very different colour, loquacious and gossipy; within his department there were Gp Capt Ops and Gp Capt Plans. Gp Capt Ops was my immediate boss; at first he was Alan Frank, an old Etonian with strangled accent to match; later Michael Beetham, an essentially reasonable man who later rose to the dizzy heights of Chief of the Air Staff and five-star.

Furner, as a Wg Cdr, was known as Ops 1: my task was to plan the action to be taken, in the event of a war emergency, by our V-Force bombers (eventually by the end of 1962 to reach a total of 144), and by the 60 Thor missiles (on 20 sites) which had started coming in from the States by late 1958—in other words, design the war plan of Britain’s deterrent force if deterrence should fail, a task not to be taken lightly. This meant the apportionment and coordinates of targets, the design of routes to and from targets, the collation of intelligence on defences, release codes and a host of other details. There was a strange air of unreality about all of this, for two reasons. In the first place, we were planning precisely that which should not happen; but then it was argued that, without such a plan, the Force would lose credibility. Secondly, there were two plans: one with NATO and the other on our own. I think the politicians saw the need for the latter simply to justify the word independent in describing the British nuclear deterrent. It was certainly extremely difficult to conjure up the circumstances in which the independent plan would be activated. For those of us who had operated in Bomber Command during World War II, the contrast could not have been greater. The 1939-1945 period saw 1,400 nights of bomber operations, dropping in total some half a million tons of high explosive: the war plan at the height of the Cold War envisaged a single bombing raid dropping the equivalent of a 100 million tons and the aircrews, if survivors, landing anywhere east of the UK.

I had two Sqdn Ldrs to attend to the details: their job was to interpret the plan to each individual crew on each V-Force base. They were John Rowell and Ulf Burberry at first, and later Ken Hunter, Frank Welford and Bill Bailey, all very hard-working and loyal chaps. Burberry and Hunter went on to higher ranks. I’m still in touch with Frank Welford in New Zealand.

Much of my time was spent in liaison with the Americans and NATO staffs in order to co-ordinate plans. Frequent conferences were necessary with the HQ 8th Air Division, USAF, co-located with us on the other side of High Wycombe; and we made annual visits to Strategic Air Command (SAC) HQ at Omaha, Nebraska, to ensure that our plans were complementary with theirs for the vast force of B47s. The NATO co-ordination was equally essential since a proportion of the Valiant squadrons were “assigned” to SACEUR, which meant that the latter took control of them at a high alert condition. By 1963, the whole of the V-Force would be “assigned”.

Looking back on that period from the end of the Century, it does seem that the Cold War was at its most tense. Take a look at some of the relevant happenings in those years from 1960 to 1962:

1960: Ballistic Missile Early Warning (BMEW) established at Fylingdale; US Pilot F G Powers shot down over the USSR in a U2 spy plane; Order placed by the Ministry of Defence for Blue Steel stand-off weapon; Display scramble of 4 Valiants, 4 Vulcans & 4 Victors at Farnboro’ airshow; Initial US/UK conferences on “Skybolt” missile.

1961: Construction of Berlin Wall begun; Exercise “Micky Finn” begun in Bomber Command to test readiness of V-Force; Assigned Valiants begin Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) status, 1 a/c per sqdn.

1962: Blue Steel successful launch and operational deployment with Vulcans; QRA status throughout V-Force, 1 aircraft in each squadron at 15 minutes; Intelligence Report of Soviet test, a 57 Megaton weapon, over Novaya Zemlya; Cuba crisis.

That last item—the Cuba crisis—needs amplifying. It happened in October. Khrushchev had a devilish little plot going with Castro of Cuba. Preparations were being made—and seen by US spy aircraft—to set up missile pads on the island and to despatch missiles (which could be nuclear tipped) to within 120 miles from the Florida coast. President Kennedy could not accept this situation and declared a blockade to stop and search Russian ships crossing the Atlantic. For a week around the 20th of October there was the most tense atmosphere any of us could remember in the whole of the Cold War period. Hardly any military aircraft were flying in NATO nor in the Warsaw Pact. All were on the ground in increasing states of readiness. SAC was on its highest peacetime alert condition. Our own Bomber Command—the V-Force and Thor missiles—were at a similar peak readiness: there were almost 144 bombers and 59 Thors at readiness, but not dispersed. The C-in-C did not wish to highlight the alert condition to the public by dispersing his force. Much of the operational staff of the Headquarters were “down in the hole”—ie in the underground Operations Room—monitoring the situation as it developed and keeping tabs on the status of the Force. Pat and Richard didn’t see much of me that week. When the Russian ships finally turned about and headed east, the world, and our HQ, gave out a collective sigh of relief. That was the closest the world ever was to the madness of World War III. As I said earlier, without nuclear deterrent forces on both sides, without the “balance of terror”, war could well have been accepted as necessary by one side or the other.

A good deal of my time was spent also in briefing various people and organisations on our plans. During my stay at High Wycombe, there were some 40 such briefings. My listeners included the Secretary of State for Air, the Chief of the Air Staff, Commanders-in-Chief of other Commands, NATO Commanders, SAC Commanders, Staff Colleges, Training Schools and Universities. Those which took place in our own Headquarters gave the opportunity to put on a presentation which, for those days, was quite impressive. Of course there were slides, remote controlled, but initially there was something missing: the lights had to go up to illustrate maps and I therefore needed to show those maps in the dark. The answer was simple. Down one side of the small theatre, put up a huge map on the wall, overlay with day-glo strips for routes and switch on an ultra-violet light above the map. (I’d first seen this sort of effect at the Crazy Horse Saloon on Avenue George Cinq, where a top hat and a stole, illuminated under ultra-violet, became entwined to the dialogue of “John and Marsha”). I remember one strange moment at the end of one of these presentations, when Julian Amery, who was then Secretary of State, asked the Chief of the Air Staff accompanying him “Now, tell me, CAS, if you were a Russian Marshal listening to all that, what would be your reaction?” It proved to be a bit of a fast ball; CAS didn’t quite know how to answer and the C-in-C stepped in after an embarrassing pause to say that he’d probably be quite impressed, or some such.

The co-ordination necessary with Allies and some of the presentations meant that there had to be quite a bit of air travel—but by commercial airlines; for instance, three times to Offutt AFB, Omaha, via New York or Washington; six times to SHAPE at Versailles just to the west of Paris; and once each to Oslo (NATO’s northern region) and to Cyprus. On those occasions Pat and Richard were on their own (in addition to the Cuba week) but she had many friends around the “Married Patch”. Richard was doing well in the Naphill School just down the road and was progressing very satisfactorily with the piano, passing both Grades I and II with distinction and winning prizes at two successive Reading and District Music Festivals. In the meantime Peter had, coincidentally, also passed Grade II piano whilst in Upper IVA at Stamford and had sung in the School’s choir in a concert broadcast on radio’s “Sunday Half Hour”.

Social life was hectic: much to-ing and fro-ing between Quarters and many occasions, Guest Nights and so on, in the Mess. It’s extraordinary to think back that, then, a majority smoked. The air would be blue in No 52 when we hosted a party—cigarettes displayed around the living room, ashtrays everywhere. Crazy. Once again, I don’t think I took my full leave entitlement, but we did get down to our favourite hotel in Bournemouth (from where, years before, the Singer had been stolen) in 1961; and in 1962 we planned something a bit more adventurous—well, for those days it was. My brother Ken’s family of 4 and ours also of 4 decided to rent a villa in Playa de Aro on the Costa Brava for a couple of weeks, not counting the travelling time. We took two cars and drove through France, taking three days each way. The sun, sea and sand at Playa was splendid, the place was thankfully not too crowded and I was able to practise my Spanish. On the other side of the coin, the villa was furnished to a very basic standard, the maid thrown in with it was useless and a visit to a bullfight by Ken and me put us off for life.

Before I leave High Wycombe and the year 1962, there is one little career matter to mention. I was now 41 and it was the practice to confirm round about that age that one would continue in an RAF career until final retirement. In the words of an Air Ministry letter to me dated 29th August 1962—“I am commanded by the Air Council to inform you that.they are prepared to offer you service on the Active List until you reach the age of 55 on 14th November 1976.” Things were now different indeed compared with the wretched days 14 years before at Middleton St George. I was lucky: some were not: some found themselves on the labour market at a difficult age.

For a time there was slight confusion over my next job. It was reported to me that I had been selected to return to the USA. That would have been remarkable. The US posts are well sought after. Chaps rarely, if ever, go there twice. Sure enough, it was soon changed. I was to be posted to Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) in Versailles, to a Group Captain post (presumably as an Acting Group Captain), but not immediately. First, in January 1963, I was to attend a course at Latimer—the Joint Services Staff College, thence to France. Latimer being where it was, a mere 8 miles east of Bomber Command HQ, we could stay in 52 Greenwoods until the course finished, which was good. Before I even entered Latimer House, there was to be a very pleasant surprise in the New Year.