Yes – the nice surprise was contained in the New Year Honours List of 1st January 1963. I had been appointed OBE and it really shook me. It must have surprised the family in Southend, too, because a local journalist apparently phoned my brother Ken and asked whether there was any connection: Ken denied any knowledge – maybe he thought it was a joke. The more irreverent among us of course reckon that it’s an acronym for “Other Buggers’ Efforts” whereas the MBE would be “My Bloody Efforts”. Amongst the congratulatory letters was a very glowing one from Sir Bing and another, equally sincere, from Iron Jaw Jack.

So here we are at the beginning of 1963 with the prospect of a Paris posting, but, in the meantime, a course at the Joint Services Staff College, Latimer. The aim of the course was said to be: “to train officers to fill Joint Command and Staff appointments by studying modern military matters on a Joint Service basis and by widening their knowledge of inter-Service problems, thus developing that inter-Service teamwork which is essential for mutual understanding and efficient working between the three Services.” The course was huge – there were about 70 of us – Royal Navy, Army and RAF, plus visitors from Commonwealth and Allied Services. The Commandant at the time was Major-General Deakin and all three Services were represented on the lecturing staff. The total of RAF pupils was 15, 13 pilots, 1 navigator (yours truly) and 1 engineer; they were all Wing Commanders.

It so happened that the first two months of 1963 were the most severe winter months since 1947. It had started snowing on Boxing Day 1962 and it went on and on for nine whole weeks without let-up. A very strong High Pressure centred itself over Scandinavia and stayed there for two months, thus giving an easterly to northeasterly airflow over the UK. Every now and again Lows would pass south of us on an easterly track dumping snow on their northern flanks; occasionally – and this was fascinating – fronts would develop over the Baltic and come at us from the east, every bit like a conventional warm front from the west, dumping yet more snow. We had our fair share in Buckinghamshire: I can’t remember more snow in any winter in the whole of my 80 years of life. One of these days we might get another. Watch out for High pressure over Norway or thereabouts! Anyway, the point was that the Chevvy was slithering about all over the roads every morning and evening getting to Latimer and back.

By March the weather had got back to normal. Peter, now 14, went off to Paris with a School party and later prepared to take the first of his O Levels. Richard was still at Naphill School, passed Grade III piano with distinction, and again entered the Reading and District Music Festival with great aplomb; indeed, after hearing 21 duos playing, the Adjudicator asked Richard to accompany him in a duet – “This is quality” he said; and Richard went home with a Silver Medal. Richard was also able to accompany Pat and me to Buckingham Palace for another Investiture, this time by the Queen Mother. Both sons had now had the opportunity to visit “Buck House” for a formal ceremony.

The course was particularly useful in that one’s eyes were opened to the problems of the other two Services. It comprised a number of single- and tri-Service exercises, many lectures, the writing of papers (including a short novel and an in-depth study of the future of Communism); and, at lunchtimes during better weather, an introduction (for me at least) to croquet, a game of devilish tactics in which you could be downright spiteful to your opponent. A course of this calibre invited very high level speakers – military, political, social – for instance, on the military side, Mountbatten and Montgomery. There was a memorable occasion when the clipped tones of Monty swirled around us in the lecture hall. He had been in the past a provocative Deputy SACEUR. He was holding forth on the “trip-wire” concept in Europe (we’re still very much in the Cold War). “All that’s needed is for one American GI to be killed”, he said, “if necessary I’ll kill one myself.” A joke, yes, but everything Monty said sounded so serious.

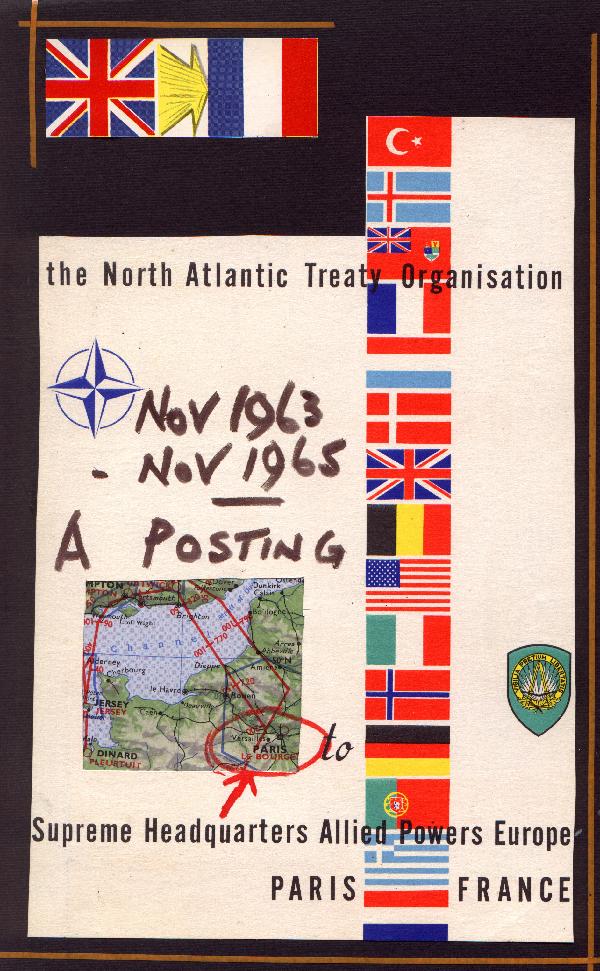

Towards the end of the course, the promotion list of 1st July 1963 brought another piece of good news – although this time, not surprising, since I was now being awarded the substantive rank of the post I was to go to, Group Captain, and wouldn’t have to be an “actor”. They didn’t want me for the new job until November; thus, whilst still living in 52 Greenwoods, I was employed as supernumerary in one or two ad hoc tasks for Bomber Command and the Air Ministry. In early November, Pat, Richard and I left the UK again and headed for SHAPE. A rental wasn’t immediately available so we installed ourselves at first in “Le Cedre” Hotel in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. We stayed there for 17 days and then moved to Home No 18 at 2 Parc du Chateau, Louveciennes, Seine et Oise, west of Paris. Parc du Chateau was a complex of apartment buildings spaced out very elegantly in the attractive grounds of a stately home. We were on a second floor. Our apartment had two bedrooms and a small balcony; all the rooms were rather on the small size but they were adequate. Louveciennes was a charming little village, well known to a number of impressionist artists, particularly Sisley.

Whilst we were staying at “Le Cedre” – on 22nd November – we came back to the hotel in the late afternoon to see everybody there bunched around the TV set in the foyer. Kennedy had been shot in Dallas: like everybody else we were shocked and were able later to recall exactly how we first learnt the news. It was grey and drizzling in Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

Let me explain where we are exactly. SHAPE – you’ve seen in the last Chapter what the letters stand for – consisted of a large number of temporary one-storey buildings at Camp Voluceau, at Rocquencourt, a mile or two north of Versailles. Both St-Germain-en-Laye and Louveciennes were very close by. All of them were about 10 miles west of Paris. NATO Headquarters was based in Paris and thus SHAPE – the top of the military hierarchy in Europe – was right on its doorstep. The Commander in SHAPE was, and is, Supreme Allied Commander Europe, SACEUR; and his opposite number across the Ocean was SACLANT at Norfolk, Virginia. Subordinate to SHAPE were three major regional HQs for North in Norway, Centre in France and South in Italy.

I was assigned to the Operations Division of SHAPE and, within the Division, specifically to the Nuclear Activities Branch. The work therefore was very much a continuation of my previous job: although widened somewhat to embrace the international scene, it was still largely an Anglo-American effort. There were many Americans at SHAPE of course, and particularly in my area of work. SACEUR was always American: the first had been Eisenhower, in 1963 it was General Lemnitzer. Deputy Saceur, always a Brit, was our own Marshal Tom Pike, a very gentle man and previously Chief of our Air Staff: he had a Group Captain Neil Cameron as his aide, a name to conjure with ten years later. In charge of the Operations Division was a USAF Major General Nielsen and reporting to him was an American Army Brigadier Coffin as Chief of the Nuclear Activities Branch. Within the Branch was a Nuclear Plans Section which comprised mostly US, a German Colonel and myself. To the 12 countries who had originally signed the NATO treaty had since been added Greece and Turkey in 1952 and West Germany in 1955, thus making a total of 15.

All of the 15 countries, except Iceland (no military), had representatives working at SHAPE. Well – I say working, but let’s be honest, it was principally the Americans, the British, the Canadians, the French and the Germans who kept the thing moving along. That line-up was reflected also in the nuclear business for obvious reasons. Unhappily, the French Government was considering a departure from the structure – more on that later. In our tight little section we had a USAF Colonel Dick Scott, whose favourite expression was “Let’s not fight the problem, fellas”, a US Naval Captain and a Luftwaffe Colonel Hans Schmoller-Haldy. Now Hans was a very nice guy indeed: he had been a night fighter pilot during World War II and he and I would sit down over a beer and discuss dates and times and places in order to figure out whether my Stirling or B17 had been in the same piece of sky as his Messerschmitt. Sometimes we’d score a hit, metaphorically. (Why can’t the Irish do that? – Why must they hold grudges 300 years old? – Religion?) Before I arrived, Hans had been responsible for carrying out many presentations and briefings, in English, to various individuals and groups, that is, on what was happening on the nuclear scene. As time passed, I took on more and more of such briefings and it seemed that the frequency increased as my two years went by. The style and content of the briefings would be dependent on the audience and the facilities available, but generally speaking they would be given against the backdrop of a screen and slides which I designed. The following list of some of my listeners may seem academic but it is revealing that many busy men relied more on the spoken word rather than the written:

The North Atlantic Council in Paris

The Military Committee in Washington

The US Atomic Energy Commission

Lord Shackleton, Minister for Air, UK

Mr Fred Mulley, Deputy Minister of Defence, UK

General Lemnitzer, Saceur

Marshal Pike, Deputy Saceur

The US Ambassador to NATO

The US Deputy Secretary of Defence

Representatives of HQ SAC, Omaha

National Military Representatives, SHAPE

Saceur’s Scientific Adviser

SHAPE Technical Centre at The Hague

Team of British and French Scientists

Deputy Chairman, US Joint Chiefs of Staff

Students from NATO Defence College in Naples

Sundry Generals from UK, US and Germany

Staff College Students from UK, US, Canada, Belgium and Italy

Undergraduates from US, Iceland and the London School of Economics

German Radio and TV representatives

The list, whilst not exhaustive, also illustrates that content had to be flexible and that one had to be mindful of the limitation known as “need to know”. That “need to know” requirement was very zealously guarded in SHAPE. Within the NATO environment there were the usual classifications preceded with the word NATO – NATO Confidential, NATO Secret and the awesome NATO Cosmic Top Secret. That word Cosmic was brilliant: but most things, however solemn, get derided in time: CTS soon became something a lot more mundane – coffee, tea and sugar. Occasionally papers would float across my desk with “ABC eyes only” – American British and Canadian (ie all the English-speakers); sometimes “US/UK eyes only”. I can’t vouch for it, but perhaps there were similar papers floating around for “GR/TU eyes only”!

The second item in that list deserves a more detailed description. The Military Committee – the highest Military organisation in NATO – consisting of 14 Chiefs of Staff in its formal role and permanent representatives in Paris for the routine – met in October 1965 in Washington, DC. Brigadier Bob Coffin and I were tasked to brief them in the Pentagon. On arrival, we were guided downwards to an underground briefing room where the illustrious 14 Generals, Admirals and Marshals were assembled waiting for the word from SHAPE. I had a large container of slides – about 50 of them, numbered and in order, of course, and handed them to the projector operator, a hoary old US Army Staff Sergeant. There was a stage for me to speak from; the slides were to be shown by back projection, that is, the projector and its operator were behind the screen and thus also behind me. There was no remote control. I had to call for slides as I wanted them. After being introduced by Bob Coffin, I started off with a few introductory words and then called for slide No 1. Up came Slide No 2. “No” I said, as quietly but as firmly as I could, “that’s No 2 – No 1 please.” There was a shuffle behind me, followed by the unmistakeable sound of slides crashing on the floor and “Oh my Gard”. The good Brigadier Bob who was in the same Service as the unfortunate Staff Sergeant leapt to his feet at the back of the room, literally rushed down the aisle, through to the rear of the screen, and was heard to speak with furiously spitten words which one could gather were designed to galvanise the projectionist to get everything back in order. I knew this was going to take time.

So – for the next twenty minutes – you now had a situation where an RAF Group Captain, in the bowels of the Pentagon, proceeded to behave like a stand-up comic and go through his repertoire of funny stories, the longer the better and the more international the better. For instance, there was my favourite “The Fee” penned by Alexander Woolcott in his little book entitled “While Rome Burns” about what happens when a young Cadet from the St Cyr Academy spends a night with the famous Paris courtesan Cosette. There was a monologue which I had been telling for years with the title “Why Worry” finishing up with “…and if you’re going up you’ve nothing to worry about; if you’re going down you’ll be so busy shaking hands with old friends, you won’t have time to worry.” There was the definition of how success in the dining room was measured: “In Germany, by the weight of the food; in France, by the piquancy of the sauce; in England, by the quality of the table linen…” There was the golfer who, playing with his worst enemy, had three wishes granted to him. There were the three Frenchmen discussing the precise meaning of the term “savoir faire”; there was the vicar, reciting the 10 commandments, who remembered where he’d left his bicycle when he got to number 7; and so on, and on, for twenty minutes.

Although I say so myself, it all seemed to go down rather well. I received applause, in fact, before I’d even started the briefing. Bob Coffin emerged from the rear, gave me the thumbs up, and Slide No 1 appeared. “Gentlemen, my subject today…”

It must be said that the work load at SHAPE was nowhere near as heavy nor as stressful as in a national Headquarters. There was certainly a degree of over-manning in International staffs such as this, simply because all the countries, understandably, wished to have representation. Hence not only was overwork not required, it wasn’t even encouraged. It was a very pleasant two years, with a balance of work, play, social and travel which Pat and I had not experienced anywhere before.

I mentioned earlier that the French Government was becoming increasingly disenchanted with the organisation. I am sure, in retrospect, that De Gaulle was particularly unhappy with the permanent appointment of an American as Saceur. He also saw the US as the dominant operator in the NATO military structure. He wished to build up his own Force de Frappe, similar to the British V-Force, and saw it as completely independent of NATO, unlike the V-Force. During my last year at SHAPE, accordingly, it was announced that France would be leaving the integrated military structure in 1966. After I left, SHAPE was moved to Mons in Belgium and NATO Headquarters to Brussels. My memory is that the people who were most unhappy about this were the French officers on the SHAPE staff. Apart from suffering a separation from the rest of the Alliance, it meant for us at SHAPE that we were denied any more funny stories about De Gaulle; it was from them that we heard little jewels like these:

“The French Cabinet were discussing one day what to do when the inevitable happened and they had to decide where to bury the great man. The first suggestion was under the Arc de Triomphe – ‘Non, not next to the unknown soldier!’ In Les Invalides? – ‘Non, we can’t have Napoleon and De Gaulle under the same roof!’ How about the Holy Land – Calvary? ‘Ah oui, that has merit…, but we don’t want him coming back again, do we?’”

De Gaulle was being shown around an art exhibition. He paused at a picture – ‘Ah – Monet’. ‘Non, mon General, c’est Renoir’. And at a second – ‘Encore Renoir’. ‘Non, mon General, c’est Sisley’. At a third – (positively) – ‘Ah! Picasso!’ ‘Non, non, mon General, c’est un miroir.’

Dorothy and Harold Macmillan were lunching with General and Madame De Gaulle in Paris. Dorothy Macmillan, after expressing admiration for the achievements of the General, asked Madame De Gaulle, “What are you looking forward to now?” Madame, in a clear and penetrating voice, replied “a penis”. A certain frisson went round the table. The General broke the embarrassed silence – “Ma chere, I think the English don’t pronounce the word like that. It’s not ‘a penis’ but ‘’appiness’”.

In 1966 there would be no more of those. And the Alliance would have to meet as 14 sometimes without the French and as 15 at other times with them. Fortunately history has narrowed the breach. Today’s President Chirac is eager to work militarily with the Alliance, but still the American domination rankles. One wonders what would have been the outcome if, from the earliest days of the Alliance, the top military posts had been rotated through the countries, just as the post of Secretary General has, and indeed as the Chairman of the Military Committee has. (See Chapter 15.)

I suppose the international comparison story which was most useful in a place like SHAPE was to describe how different nationalities react to a funny story when they hear it. I found that it was always amusing to denigrate oneself first: “When you tell an Englishman a funny story, he laughs three times – once when you tell it to him, the second time when you explain it to him and the third time when he catches on.” Then to deride an obvious outsider: “A Russian, on the other hand, laughs twice – once when you tell it to him and the second time when you explain it to him. He doesn’t catch on.” Next to flatter a relevant friend: “A Frenchman only laughs once – he catches on straightaway.” And finally to your host or senior guest: “But an American doesn’t laugh at all because he’s heard it before.” Now you can readily see that this little piece is extremely adaptable. I’ve used it not only for nationalities, but also for Stations, Squadrons, Universities, Schools, Cities, Museums, Art Galleries, Sporting Clubs… the list is endless.

Endless, too, was the social life; much of it very formal, with fancy printed and crested (or starred, according to rank) invitation cards, coming to us from almost every country in the Alliance, including Iceland. It was impossible to return the hospitality to all the inviters – indeed, nor was it expected. There were also much less formal get-togethers with our own people from time to time, British Army and RAF. We particularly recall the friendship of AVM Lewis Hodges and Elizabeth; and of Gp Capt Jack Jenkins and Gladys. Our tiny apartment was not equipped for formal socialising; we were more likely to arrange cocktails in the Officers’ Club for as many as we could fit in. The really big occasion of the year was the SHAPE Charity Ball – the Soirée de Bienfaisance – organised by a Committee presided over by Mrs Lemnitzer, Saceur’s lady, and held in early December in the Galerie des Batailles of the Palace of Versailles. The pomp and splendour were magnificent, the setting breathtaking, the dancing floor superb, the champagne prolific, and the night long enough for many of us to finish up in Les Halles in the City for an onion soup as dawn was about to break.

There was so much to enjoy in Paris. For all our visitors – and families took the opportunity whilst we lived in France – we designed a number of tours which encompassed as many sights and events as possible. The sights included Concorde, the Arc de Triomphe, Notre Dame, Elysees, Sacre-Coeur, the Louvre, Eiffel, Bois de Boulogne, rives gauche et droite and, of course Versailles. As to events, Pat and I attended at, and took guests to, the Casino de Paris, the Lido (“le plus célèbre cabaret du monde”), the Folies Bergere, the Crazy Horse saloon (very small seats), the Opera Comique, Bouglione and Cirque d’Hiver. Perhaps the most spectacular event was the combination in the grounds of Versailles of fireworks, lights and music – undoubtedly the best organised fireworks I have ever seen.

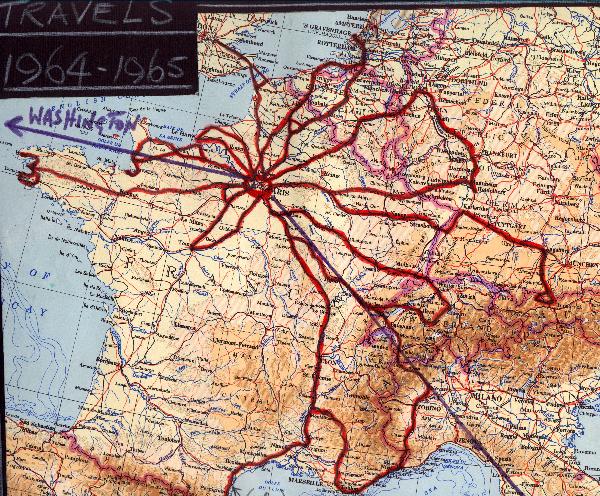

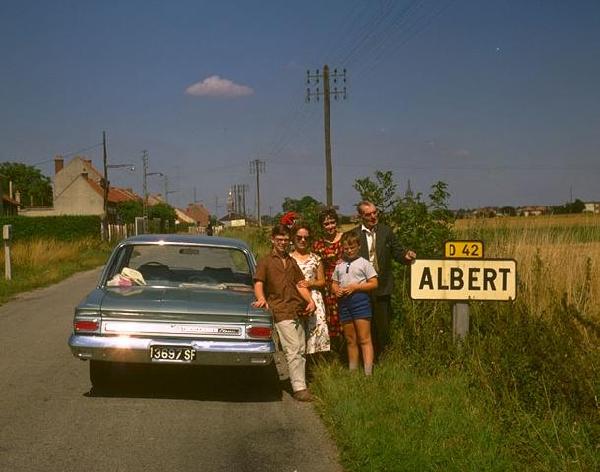

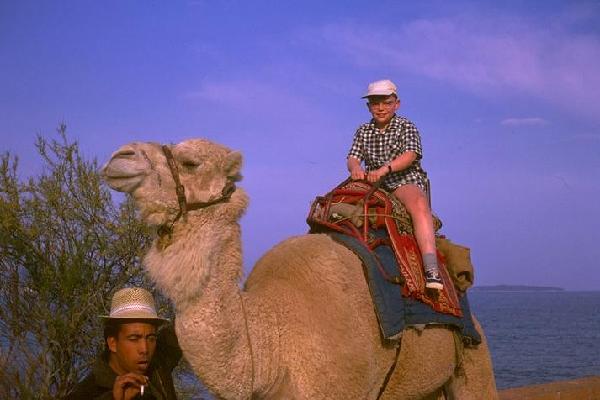

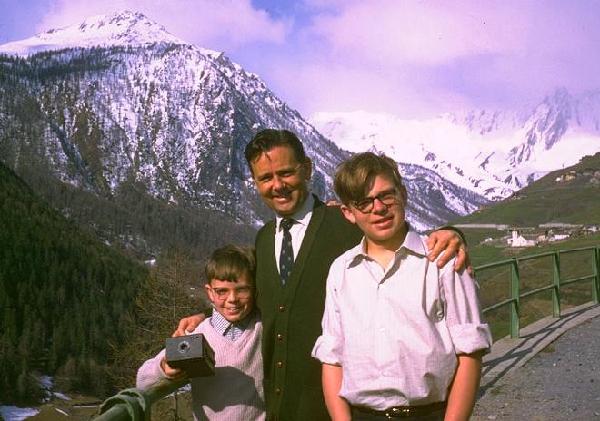

I have mentioned that in many of my previous posts, it was difficult to take all the leave one was entitled to. That was certainly not the case at SHAPE. I took every day of it and we travelled a great deal, freed from the constraint of the Channel. It’ll be boring for you, the reader, if I list all the holidays we took. Suffice to say that we drove the Chevvy, and later its replacement the Rambler, to Chartres and were intrigued to see the two completely different towers; to Orleans and Tours; to Epernay to see how Moet and Chandon produced their Champagne; to the Loire Valley to enjoy the sight of all the beautiful Chateaux, so many of them beginning with “Ch”; to the Riviera to bask in Mediterranean sunshine and to visit Bandol, La Napoule, St Tropez, Cannes, Grasse (the perfumes!), Cap d’Antibes, Nice and Monte Carlo; through to Italy via 92 “lacets” (“If they’d said that number at the beginning”, Pat said, “I’d never have gone!”); to Switzerland (twice) to gaze in awe at the mountains and to take the train up to Kleine Scheidegg; to Germany (twice), first to the Rhine and Heidelberg and later to Garmisch, Oberammergau and Ludwig’s Castles; to Normandy to survey the memorials and monuments of 1944 D-Day; and to lovely Brittany and its long coastline, so reminiscent of our own Cornwall (and home of much nicer Frenchmen than Parisians). In addition, I had the opportunity, alone, to fly to Naples to attend a conference; I took the train down to Pompeii and, since it was out of tourist season, was able to walk around the town’s remains utterly on my own; an extraordinary experience, reliving in one’s mind the horror that had happened 1900 years before.

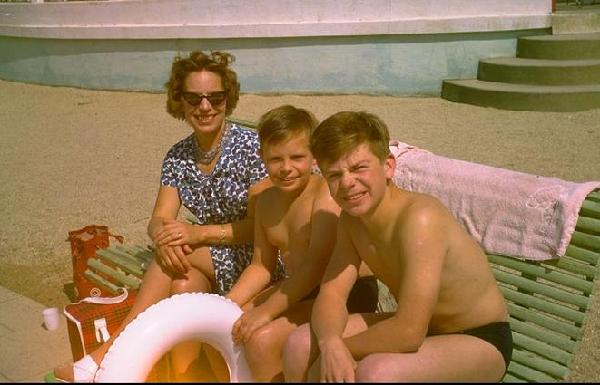

On many of those journeys we were a foursome. We were lucky with the timing of them. Peter at Stamford had passed some more of his O Levels in July 1964 and had gone up to Form VI Maths in September. He also passed Grade III at piano and he was going great guns at cricket. During the summer holidays in 1964, he took part in a game between SHAPE and a visiting British Army team. His score of 34 was the second highest in a game which SHAPE won. Richard, 9 years old soon after we arrived in France, attended SHAPE International School which demanded an early (8.00 am) departure by bus; however, we soon had the same heart-searching with the problem of continuity that we had had with Peter. For the following academic year starting in September 1964 we sent him also to Stamford and he entered in Upper II; at least he had his elder brother to keep an eye on him in the early stages. The following year, 1965, he passed Grade IV piano with distinction and went up to Form IIIA.

My tour with SHAPE finished in November 1966. I was told well in advance what was next in store. I was to go to the Ministry of Defence (Air) as a Deputy Director of Manning. Manning!? Good grief, what was this? I telephoned Dougie Bower whom I was replacing and asked him for details. He assured me it was an important and very busy job. I had known the name of Bower for some years. He was a fellow navigator and was two years older than I; I also knew that he was a Spec N and had had a good career; they had posted Bower to this Manning job, so they must have wanted high calibre people for it. I was encouraged. What a change! We’ll have to see.