That move in November 1965 was, indeed, to be a “small fish in a big pond”. Even a “Deputy Director” was ten a penny around the Ministry. Let’s be clear first of all that there had been significant changes since I was last in London. In 1957 just after I returned from the States, the three Ministries still held sway – the Admiralty, the War Office and the Air Ministry, each with a Minister. That extravagant situation couldn’t go on for much longer. Every year brought more cuts in the military and the Services were getting inexorably smaller. We were now all under one Ministry: whereas I had briefed Julian Amery a few years before in his capacity as Secretary of State for Air, we now had Denis Healey as Secretary of State for Defence, and a very good one too, as most of the military agreed, regardless of politics. He was to remain so until I had occasion to host him in 1968. At least we didn’t go as far as the Canadians, who, much to military disgust, were forced (initially) to wear the same purple-coloured uniforms.

I shall deal first with our homes during this period (November 1965 – November 1967); then the work; and finally the family which was to grow.

Neither Married Quarters nor hirings were readily available on our return to the UK from Paris. So once again we had to find our own temporary home. Home No 19 was a furnished house at 7 Burrows Way, Rayleigh in Essex. We were thus very close to my own relatives in the Southend area, including my brother Ken who by this time was very diligently building up his own business. This enabled Pat and me to organise a fairly riotous New Year’s Eve party in the dying hours of 1965. After a few months a Quarter became vacant near RAF Stanmore, northwest of London: our home No 20 was 4 Finucane Rise, Bushey Heath. The four of us “marched in” to the Quarter in April 1966. We were to march out as five, but more on that significant event later. I should mention that when I started work, I had a short and very amiable discussion with Air Marshal Sir David Lee who at that time was the Air Member for Personnel on the Air Force Board. On the domestic issue, he strongly recommended that I purchase a house and borrow like mad in order to achieve it. In retrospect, he was right of course, bearing in mind what would soon happen to the economy; but we felt we couldn’t face the aggro of letting it when the inevitable next posting came along. So we continued paying rent.

The work was entirely different from anything I had previously experienced. In the first place, I was completely divorced from flying: there was neither the time nor the opportunity to get anywhere near an aircraft, nor the occasion to consider a navigational problem. Secondly, for the first time ever I was working for a civilian boss. And he was formidable. He was a Civil Servant with a rank equivalent of Air Commodore. He was a Senior Scientific Officer. His name was Mr G A Roberts – simply “Robbie” to his colleagues – and his knowledge of manning policy was encyclopaedic. At my first meeting with him in Adastral House, Theobalds Road, just round the corner from Holborn Underground station, I knew that I had a long climb to catch up with his expertise. But catch up I would; I was determined about that.

So what was it that I had to catch up on? Under the Director General of Manning (an AVM) Robbie was D of M 1 dealing with Officers and an Air Commodore was D of M 2 dealing with other ranks. I was one of Robbie’s Deputy Directors, and specifically the one who designed the structure of the Officer Branches. The RAF had about 20,000 active officers in those days, split into various Branches – the largest being the General Duties Branch (the Flying Branch); the second largest the Engineer Branch; then the Secretarial Branch (Admin); the Supply Branch (Equipment); the GD (Ground) Branch, dealing mainly with Air Traffic Control; the Education Branch; and a number of small professional Branches – Medical, Dental, Legal and Chaplains. The task of designing the structure of the Branches was an impersonal matter. I was not concerned with individuals but with the whole.

In theory, the progress of planning tasks started with the United Kingdom’s commitments and strategies. What Armed Forces were necessary to undertake those commitments and strategies? In practice, of course, the Treasury kept a very beady eye indeed on the Defence Budget and whatever could not be squeezed into the Budget was out of the plans. The Air Staff in Whitehall would draw up the shape of the Air Force for the next ten years, based on the front line required, training backup, courses and so on. Next, Establishment staff would produce for each resulting Station, Squadron, Training unit, a catalogue of all posts by rank for each of the ten years. We – the Manners – took their Establishment and added to it sensible increments for courses and handover periods, thus creating a Requirement at each rank. The Requirement for the lower ranks, through which promotion was by time, dictated the “Into Productive Service” (IPS) figures per year. Working backwards from the IPS and allowing for failures in training gave us higher figures of people to enter training. Even further back you would have targets for initial recruitment, in the knowledge that a percentage would change their minds. Finally, how many would you ideally have responding to national advertising? [Talking of recruitment advertising, it is interesting to note that two completely different approaches to picturing service life had very different responses. To a dramatic photograph of the sharp bullet nose of the Lightning fighter with the headline – “Same old thing every day – excitement!” – there was little response from potential flyers. But to a montage of overseas bases, swimming pools, WRAFs, sporting facilities – great volumes of responses. Ah well.] The aim for the GD Branch was to attract at least 50% graduates.

Then, higher up the structure, what promotion flows were likely given the relationship between one rank and the next higher. As a general rule – but easily broken in certain areas – one could assume that any Branch structure would have posts established from the top down by the rule of three – ratios of 1,3,9,27,81,243, etc, ie a geometric progression with r = 3. In that general case, the probability of promotion, after 5 or 6 years of “wastage” in one rank, would be of the order of 50% to the rank above. But there were bound to be exceptions of course, and on one or two I shall elaborate.

So one could say that this was all simple arithmetic and equally simple geometry. But, coming straight from Nuclear Activities, it took a bit of time to assimilate this sort of stuff. I can explain it simply now: then it was esoteric. In any case, there was the vagueness of forecasting to contend with. It became almost automatic in one’s thinking that forecast figures were too optimistic, higher than the real ones when the time came. I often used to think what a comparatively simple forecasting task the Department of Education had in deciding how many teachers we wanted; you would know that the birth rate in year 0, minus a small “wastage” percentage for premature death, represented your classroom total in year 5.

In more ways than one I eventually made lighter work of it all. For instance, I circulated the following piece just before one Christmas:

“What is a manner?

A manner has nothing to do with the plural sense which maketh man: he manneth man and posteth man.

A manner works not in SW1 where the real decisions are made but in WC1 where those decisions have to be interpreted. WC1 is well recognised as “sleepy hollow” because the telephone exchange removes all plugs at 5.30 pm and nobody can then talk to a manner.

A manner is much the same sort of chap as those in SW1 – perhaps hopefully a little more numerate – but when assigned to WC1 is labelled specifically as a “manner”. The labelling is critical: the phrase “that is what you expect from a manner” or some such is meant to imply that, once a manner, one’s judgment becomes suspect. One seldom hears in a parallel sense “that is what you expect from the Air Staff” – not even from a manner: he is too busy interpreting those decisions. Indeed, if a manner ever says anything memorable at all, it is very likely to be something terribly negative like “You Can’t Have it Both Ways”, which of course any sensible chap, particularly in SW1, knows is nonsense: you’ve got to.

The manner knows he is at the end of the planning chain but must on no account highlight this point to those earlier in the chain. Such an observation by a manner is bound to bring the riposte that he will have to anticipate more intelligently. Thus he not only has to interpret those SW1 decisions that have been made but also to anticipate those that have not -–and woe betide the manner whose crystal ball is cloudy.”

I remember vividly that Robbie used to get very hot under the collar at times about the sort of plans the Establishers produced. He would draw the following analogy – and, always searching for added humour in lectures, I used this myself often. The two great musical figures Haydn and Mozart had a friendly bet one day that each could compose a piece that the other couldn’t play at first sight. The young brash Mozart dashed off a complex sequence at allegro with which Haydn had no difficulty whatsoever. Then the older and wiser Haydn wrote one chord of three piano keys – the one at the bottom, the one at the top and the third in the middle. Mozart looked baffled: “How?” Haydn played the middle key with his nose. “And that”, Robbie would say, “is sometimes how the Establishers’ work comes to us!”

To take two glaring examples of the distortions that can occur from the Establishment: firstly, that of GD junior officers – the Pilot Officers, Flying Officers and Flight Lieutenants all enjoying time promotion with no selection. The RAF is unique in the three Services in that all its fire-power is contained in its junior officers; they are the ones who go to war. In consequence their total numbers make up a disproportionately large base to the rest of the structure of senior officers; the probability of promotion from Flt Lt to Sqdn Ldr is significantly less than probability at all other levels, and less than the same level in other Branches. Therefore appreciable numbers of junior officers will remain at junior level for all of their flying careers. The situation demanded two lists for GD officers – the General List for those fortunate enough to climb the career ladder, and the Supplementary List for those who remained at junior level.

A reverse type of distortion occurred in the Engineer Branch. Because of expertise required, the Branch suffered from a swollen Sqdn Ldr establishment which could not be fully supported by the Flt Lt level. Thus we had to offer Sqdn Ldr direct entry into the Engineer Branch to those with suitable experience and qualifications.

With Defence Budgets continually coming under the knife – under whatever Government – there was often the unpleasant business of cutting strengths by redundancy, voluntary if possible and compulsory only as a desperate last resort. An “ideal” age/rank structure should not have too many people in any single year. I mentioned in Chapter 2 that the immediate years after WWI were “bulge” years (and I was in one of them). The aim in any redundancy programme was to target those years in order to straighten up the structure as far as possible. People in the bulge years are thus subject to two “laws” – (1) they have to work harder to progress up the career ladder and (2) they are more likely to be earmarked in any redundancy programme. Conversely, officers born in 1931 (a low birth and entry year) had an easier progression.

Another problem within the GD Branch which has raised its head with every vintage of manning staff was that of establishing ground posts for junior GD officers. I’m not referring here to Air Traffic Control or Fighter Control officers – they’re in a separate GD (Ground) Branch. No – the problem lies in the establishment of, say, Personal Assistants to high-ranking types, odd jobs in the Embassies and elsewhere where the Establishment staffs insist that it is a job on the ground for somebody trained as a flyer. These tasks are anathema to the manners because they increase the into-flying training figures. Flying training is very, very expensive.

Both of these last two subjects are perennials. I was not the least bit surprised that I had to return to them seven years later in my last RAF appointment (Chapter 16).

I made a number of new friends in this MOD job. Prominent among them was Group Captain George Kemp who was responsible for a wide spectrum of personnel policies: he had been a flyer during WWII but for medical reasons had had to transfer to the Secretarial Branch. He later became the senior man in his Branch when he and I were to work together again, and we have kept in touch since retirement.

Towards the end of my time as a manner, I took the opportunity to describe for Air Force-wide readers in the service magazine “Air Clues” what a GD structure was all about – in a light-hearted sort of fashion:

“A Dialogue in Pyramidology

I was having lunch with the Ruritanian Air Attache the other day. The conversation turned to officer career structures. It seems they have an ‘ ideal’ Air Force.‘How do you mean, ideal?’ I asked. ‘Simply that everything stays constant. We have a constant establishment – at every rank – constant intakes from training, constant appropriate wastage from each age band and constant promotion quotas at constant ages. Fortunately we never get involved in any wars or emergencies and nothing ever needs to be changed.’

I resisted asking him how he had obtained this happy steady state in the first place; whether it had always been like that, or whether he subscribed to the ‘big bang’ theory. All I said was ‘Tell me more.’

‘Well first of all: our ranks are similar to your Army’s. Promotion from Second Lieutenant to First Lieutenant and to Captain is by time; promotion to all the senior ranks is by selection on a quota basis. Our establishment (including all the usual allowances) is constant at:

33 Generals (I won’t complicate it with the various stellar intensities); 99 Colonels; 357 Lieutenant Colonels; 500 Majors; and 953 Junior Officers. Our total officer establishment is therefore 1942. Now, how do we fill these posts? Well, let’s start from the bottom. We intake into productive service exactly 100 officers out of training each year at the age of 22.’

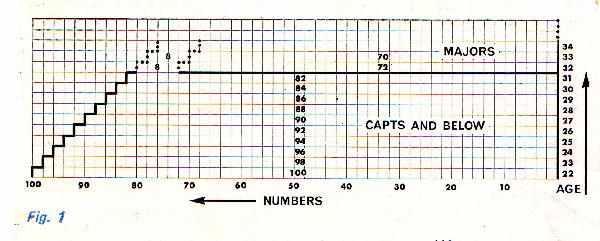

‘All the same age?’ ‘Of course.’ ‘Remarkable……Sorry – please go on.’ ‘Right. So we have 100 aged 22 at the bottom end of our structure.’ (He started to sketch out on the tablecloth. It had squares on it. The beginnings of his sketch are at Figure 1.) ‘Now as you realise only too well there are quite a few reasons to waste that figure as the years go by.’ (Horrible word, waste – part of the manning jargon – covering all modes of exit apart from normal retirement.) ‘We manage to control the wastage at this stage to 2 officers a year. So we have 98 aged 23, 96 aged 24 and so on. I shan’t bother to distinguish between the first three ranks since they’re covered by time promotion; so let’s go on up the age scale until we get to 82 of the junior officers at the age of 31 and then 80 reaching 32. It’s here – at 32 – where the first promotion by selection takes place – to Major. And we promote 90% each year, that is, 72 of the 80.’

‘72 exactly as they reach the age of 32?’ – ‘Check’ . ‘And you find the quality distribution to be right on the button each year to be able to do this?’ – ‘Naturally.’ – ‘Silly of me to ask – go on.’

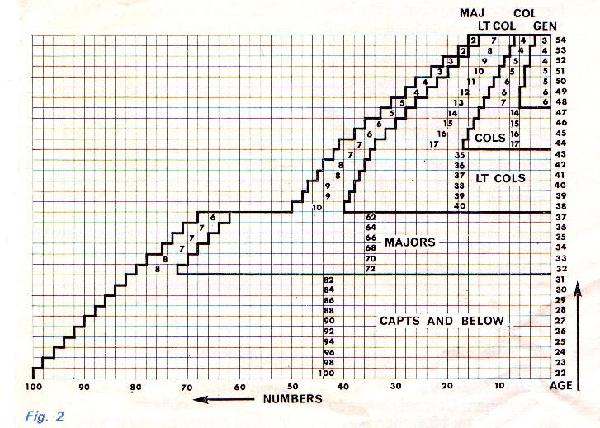

‘Right. The 72 promoted to Major at age 32 continue to waste at 2 a year, 70 at 33, 68 at 34 and so on, and the 8 unpromoted Captains waste at 1 every three years.’ (He continued on the tablecloth – Figure 2 is the final product.) ‘So year by year we reach 62 Majors and 6 Captains at age 37. Now this brings me to an important point on the age scale.’ (Wait for it, I thought.) ‘What we call the 38/16 point.’ (Snap) ‘It is here that the unpromoted Captains leave the Service, that precisely a sixth of the Majors elect to leave the Service – that is, 10 of the 60 entering age 38 – and that 80% of the Majors remaining, 40 of 50, are promoted to half Colonel.’ (Keep your eye on Figure 2 – he got a bit complicated at this stage). ‘So at age 38 we have 40 Lieutenant Colonels and 10 Majors. The Lt Cols now waste at one a year and the Majors at one every two years.’

‘And those Majors don’t have another whack at half Colonel?’ I looked incredulous.

‘Of course not. I thought I’d already made it clear that exactly the right number and proportion are promoted to each succeeding level at exactly the right age.’ I looked suitable chastened. ‘Please go on.’

‘The next significant age is 44. Those entering age 44 have now wasted to 34 Lt Cols and 7 Majors. Of the 34, exactly 50%, 17, are promoted to full Colonel. The Colonels and unpromoted Lt Cols continue to waste out at a rate of one a year. When we enter age 48 we see 13 Colonels, 13 Lt Cols and 5 Majors. Of the 13 Colonels, 46% – 6 – are promoted to General. From here on until the 54th and last year, the newly promoted Generals waste out at one every two years and the unpromoted Colonels continue to waste at one a year. Thus in that 54th year you see 3 Generals, 4 Cols, 7 Lt Cols and 2 majors, who will all retire on their 55th birthday.’

‘And that’s the ideal way to man the establishment you were talking about earlier?’ ‘Yes. Add up all the figures for each rank and you’ll find they all fit.’

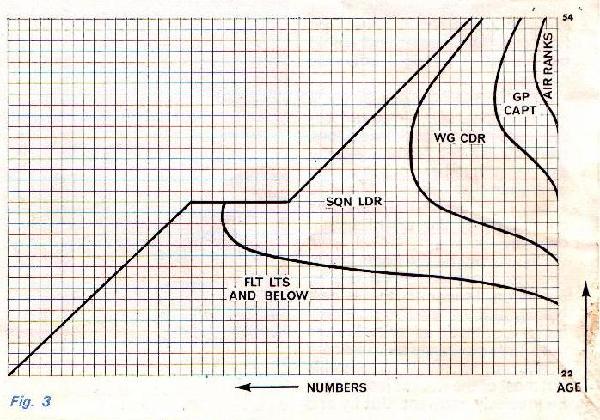

Inevitably we got on to our career structures and I began by explaining that we drew the same sort of ideal pyramids for the General List of each Branch, but that they represented an aim which we never quite achieved. ‘We don’t have the mathematically precise quality distribution that you have: we make allowance for the fact that there’ll be the fast runners, the average chaps and the slower moving ones. So that our ‘ideal’ diagrams – if we drew one to your figures – would look more like this.’ (And I drew Figure 3 – curved stuff this time.) ‘But that’s still an ideal – and a long way out of our reach. We’re beset by various facts of life that prevent us from actually achieving it. Nevertheless we’re guided in many of our policies, of manning and of promotion and so on, by these ideal diagrams.’

‘What facts of life?’ asked my RRAF colleague.

‘Well – have another coffee, sit back and hear this:’

‘First and foremost, we have not enjoyed your immunity from the more important military happenings in the last quarter of a century and in consequence our establishment has not, and will not, remain constant. For instance, the establishment of RAF officers in 1939 was 7,500, in 1945 100,000, in 1950 18,000, in 1955 25,000, in 1960 21,000 and on 1st September 1967 it was 18,000 again.’ (Note 2006: 4,000) You can’t adapt your neat little steady-state patterns to that sort of cycle. When we draw up our ideal career structures, we always look as far ahead as we can, usually ten years, but with the world as it is, and with politicians as they are, Heaven knows what will have happened by the time we get there.

We do try to keep the General List of each Branch as constant as possible, and use the Supplementary List to absorb the ups and downs in the establishment. Even so, any changes in the upper rank structure – certainly anything significant in Lt Col and above – force us to modify even the General List structure.’

‘Second, and following on directly from that first point, our intakes from training and therefore recruiting targets have to vary. Mind you, between major changes of policy we do our best to keep the flow as even as possible, but those major changes mean there are fat years and there are lean years. Obviously the early 1940s and the early 1950s were fat, and the lean years after WWII and the Korean War were very lean indeed. Let me give you just one example. In the three-year period 1954-1956 we saw as many pilots and navigators emerge from the training machine as in the following nine years from 1957 to 1965. That sort of thing means that you create a bulge or a waistline in the structure and however much you try to even it out, it inevitably stays with you in some measure and moves up the age scale as the years go by.’

‘Third, unlike you we don’t manage to get everybody out of training at the same age; we tap many and varied sources and age bands for our recruits and although generally speaking we expect that the majority of our officers will enter productive service in their early twenties, we have a potential age spread as wide as 20 to 39. And although we have similar time promotion to yours in the junior ranks, the periods taken to get to Flight Lieutenant are also many and varied, depending on the Branch, the type of entry, and the entrant’s qualifications and previous experience.’

‘Fourth – yes, thanks, I’ll need another coffee – you passed a bit glibly if I may say so over your wastage rates. We plan on certain percentages of each age band, but we do not control it precisely to that rate – nor would we wish to. In fact, we plan on 2% wastage per year up to age 43, then a higher figure of 4% per year from 43 to 50, and finally at the top end we plan on 10% per year from 50 to 55 – a higher rate which we justify on the basis of officers wishing to settle themselves in the last years before retirement. We also have an option to leave at the 38/16 point, similar to yours, and we plan on a particular exit percentage – usually about 25% on our General Lists; but here again we cannot and would not control it by rigid inflexible means.’

‘Fifth and last – because there are variations, sometimes unforeseen, arising from all these factors, we can’t like you promote exactly the same number to each rank each year. If we did, we’d have to accept being under- or over-borne and we’d hit the establishment only by accident. Mind you, we’re allowed by the financiers to stick to a predetermined rate to Squadron Leader in the largest Branch and we overbear accordingly – but that’s as far as licence goes. We try to smooth things out as much as possible but most of the quotas just cannot be precisely constant. ‘By and by, however, they average out to the plan; they may hover around it within a band of say plus or minus 10%. Now at the present time – in the latter half of 1967 – we have a new factor: some redundancy is necessary because we can’t absorb the downward trend in establishments by normal factors. During the redundancy period we hope to keep more or less exactly to the ‘ideal’ promotion rates. Even after the redundancy period, when of course the total strength of each Branch will be a little smaller, you shouldn’t necessarily assume that we shall be cutting quotas on our General Lists.’

‘If you look at the bit of the tablecloth with your diagram on (Figure 2) you’ll realise that if the area of say Colonels and above or Lt Cols and above is to be cut by 10%, then you can either cut the promotion quotas by that same 10% and retain the promotion ages, or – and this is what we shall probably try to do – you can retain the quota and raise the age slightly. It’s a matter of simple geometry.’

‘So there you are. That’s how it is with us. But you have to realise that, despite all these reasons why we haven’t got an ‘ideal’ structure in practice, at the back of our thoughts all the time is the idea that we must seek to go towards it, to have it as an aim. And that idea is reflected in so many of the things we do – how many we promote, at what average age we promote, how many we should intake, from what source, how many should be transferred from Supplementary List to General List and in what age brackets, and so on. The ideal structures guide us in smoothing out our variations and provide a framework within which to judge policies and avoid promotion blockages. In short, although we never seem to reach your happy ‘steady state’ we are always striving towards it.’My Ruritanian colleague had to get back to his office. He looked a little dazed, but I thought I detected a glint of envy in his eye. I learnt later that he was preparing a paper to send home about the need for more flexibility in their structures. He is a Lieutenant Colonel and is 45 years old.”

As I reproduce that piece nearly 40 years later, I have two immediate thoughts – today’s staffs will still be living in a reducing Air Force, but they will have considerable computing power to aid them in their task.

Finally, a word about the Ministry as a whole. There was a less than serious comparison in those days between doing business with the MOD and having sex relations with an elephant. Everything was done at a very high level, you were likely to get thumped on in the process, and it took a very long time for anything constructive to appear.

So much for the work from November 1965 to November 1967. What of the family during that period? There was a lot going on. Peter ticked off successfully further O Levels and a couple of As, took on the responsibility of House Prefect, appeared in the top 2% of a National Maths exam, captained the Stamford senior cricket eleven and scored the highest score (38) against the Old Boys on Speech Day. On preparing to leave Stamford, he had offers from six Universities. In May 1967 he signed a contract with IBM, the giant computing company, for a ‘sandwich’ arrangement at Brunel University: he was to be an Industry based IBM Systems Analysis and Programming Student and was to spend alternating periods studying at Brunel and working at IBM offices; the course at Brunel would be their 4-year integrated honours degree course in Mathematics with Applications to Management. He started in September 1967.

Richard, meanwhile, was progressing through Forms IIIA, Remove A and Lower IVA, earning himself the Form Prize for each of 1966 and 1967 and the ‘Tinkler’ Prize, also for each of those two years, for piano. (What an appropriate name for the piano prize!) He passed Grade V at piano with Merit and was awarded a Marshall Exhibition in 1967.

As a family we took a number of holidays – in London, on the south coast and in Pembrokeshire, the last two in static caravans which gave us a sufficient taste for caravanning to wish to take it up later with our own vehicle. During this MOD tour, we did not venture abroad.

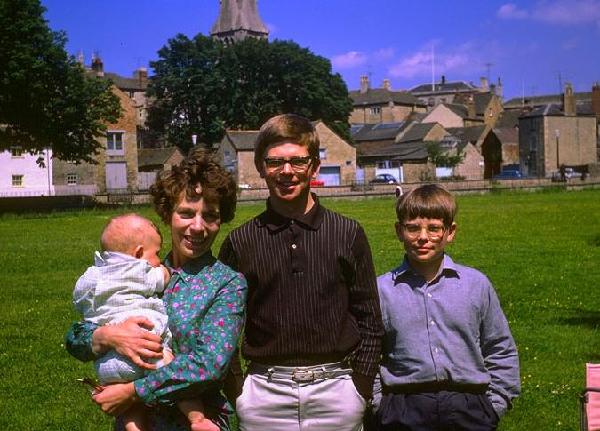

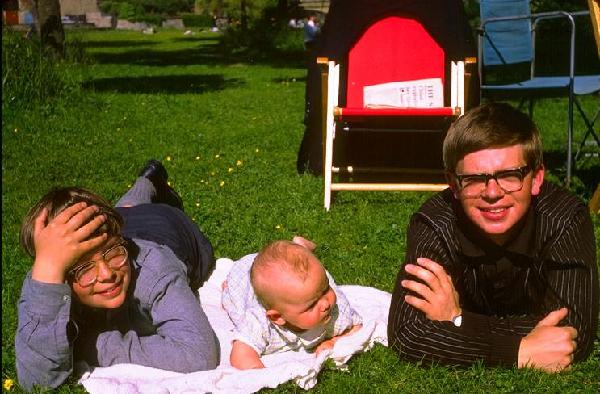

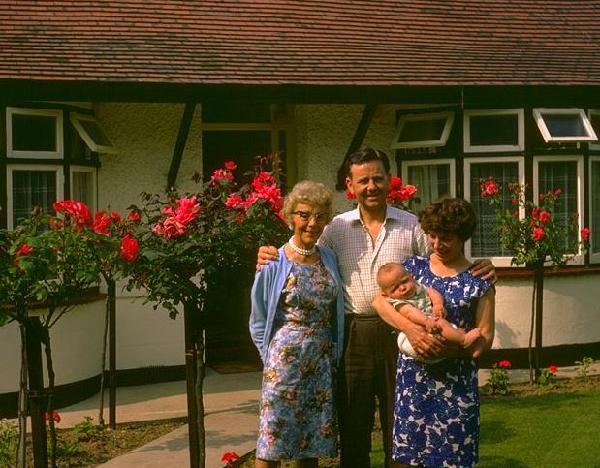

The really important family news of 1967 was the birth of our third son, Jonathan. Pat was 42 and I was 45: Pat had a very rough time indeed. There was a last minute emergency, the baby was strangling himself with the umbilical cord, Pat was rushed from one hospital to another and was subjected to a Caesarean operation with no general anaesthetic. She was surrounded by various grades of medics. She could sense quite clearly the progress of the surgery. When I first saw her after the birth, it was heart-breaking to see the long scar. But Jonathan was fine – a very beautiful baby, as everybody at the hospital remarked – and Pat soon recovered from the ordeal. A few months later she looked ravishing in the grounds of Buckingham Palace when we were invited to the first Garden Party of the 1967 season. Pat’s parents looked after Jonathan, as they did also at Finucane Rise when the four of us went off on holiday.

As the year 1967 approached its end, a fellow Group Captain in Adastral House who was responsible for postings of senior GD officers popped his head around the corner of my office door and announced that I had a very good chance of making two more ranks (unusual to say things like that!) but that first I had to prove myself as a Station Commander. I should prepare to take over command of RAF Scampton in the New Year; before that I would need a Vulcan refresher at RAF Finningley. Wow! I was conscious that never before had a Navigator commanded a front-line operational, as opposed to a training, Station.