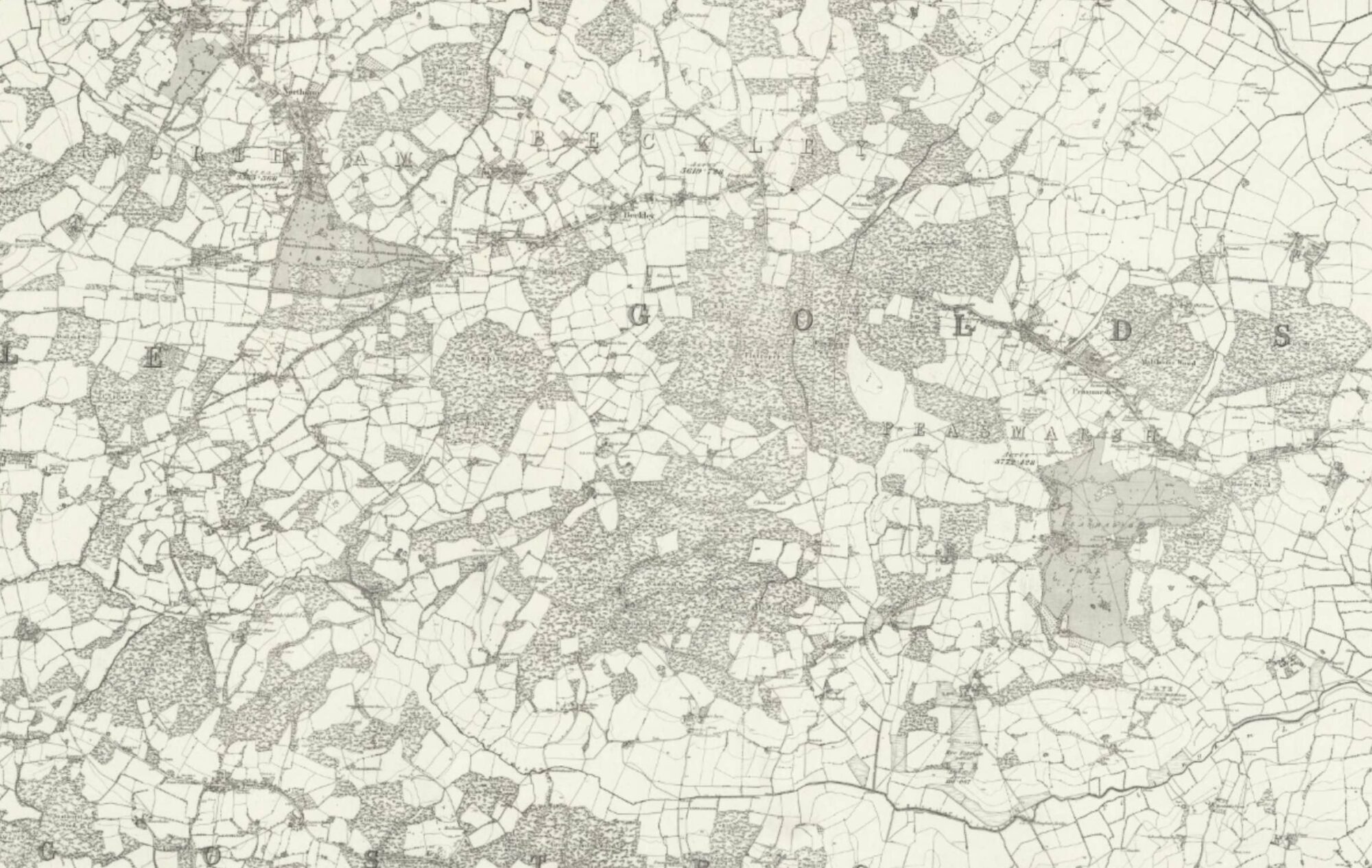

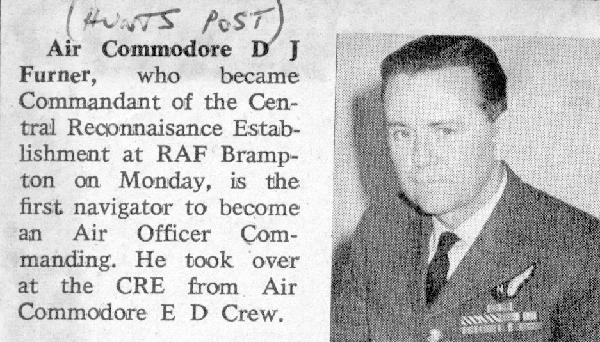

Yes, the powers that be knew I was going to be promoted on 1st January 1969. I could not therefore remain as CO of Scampton. I had to be posted to an Air Commodore post. Apart from the protocol of the situation, the financiers in the background frown on overbearing of rank. It was to be another command post – an Air Officer Commanding (AOC). CRE was still a small Group in the new Strike Command, alongside the mighty No 1 which comprised all the Bombers, No 11 all the Fighters, No 18 Coastal and No 90 Signals. CRE was based at RAF Brampton which housed a number of different units. As well as CRE, Brampton held HQ Training Command and the Joint Air Reconnaissance Intelligence Centre (JARIC), the latter being one of three units under my command. The other two were RAF Wyton which operated a number of reconnaissance Squadrons and the Joint School of Photographic Interpretation at RAF Bassingbourn. Once again, the press commented that I was the first navigator to attain a post of Air Officer Commanding. What pleased me most was that amongst the letters I received on the promotion were those from the Mayor’s Parlour Lincoln, the Lincolnshire Constabulary, the Urban District Council of Gainsborough and the Lincolnshire Echo editor. After a spot of leave I was to take over from Air Commodore Ed Crew at the end of January.

I was conscious of the fact that there had been rapid turnover in the post. I recall that three people had gone through CRE in the previous 18 months. It was symptomatic of the possibly ephemeral nature of the Headquarters – it was continually being sniped at by the financiers. As it happened, I was to be the last AOC of CRE and I was to close it down, but at least I was to be settled there for almost two years.

My early days at Brampton were marred by an irritation concerned with the AOC’s quarter. It is an unwritten, but inflexible, rule that posts of this calibre carry with them an ex-officio quarter. The day you’re moved from such a post, you quit the quarter. My predecessor, Air Cdre Ed Crew, didn’t. He seemed to have a chip on his shoulder about being told to go at such short notice: since it was on promotion to AVM, I thought to myself – he should be so lucky. It proved to be an acutely embarrassing business. From the start, I just assumed I was going straight in – unless, that is, the condition of the quarter demanded a lot of redecorative work. No, he couldn’t move his family, he said, at this short notice; they were staying until he could find suitable accommodation for them. Well! I stayed in the JARIC Mess for a bit (Brampton had two separate Officers’ Messes), and Pat and Jonathan remained behind in Norwich. Since February 1969 was an extremely snowy month and the weekend travelling was thus made more hazardous, my good humour was being stretched to breaking point. At last, I had to explain the situation to the Admin people at Strike Command HQ at High Wycombe. They were dismayed and sympathetic. Pressure was brought to bear from on high. Ed Crew at last pulled his family out of the quarter; I travelled to Norwich once more to bring Pat, with Jonathan, to “march in” to her 22nd Home – No 37 Park Lane – which, you must agree, is a nice change from Trenchard Square.

So, settled now and the unpleasantness over, here was a fascinating task for the next 21 months.

The tasking channels were a trifle odd: orders were not necessarily originated from HQ Strike Command, our structural masters, but also directly from the MOD – Operations, Intelligence, Operational Requirements, Military Survey; and from the sister Groups Coastal and Signals on matters solely affecting them; and from further afield, for instance, GCHQ at Cheltenham; and finally, from anybody else on an ‘old boy’ basis if time and effort would allow. To Strike Command I was known as the AOC; to MOD and the others I was the “Commandant” CRE. In addition to the command and control of CRE’s three units, the Establishment was responsible for advice on all matters affecting reconnaissance.

My three units were all doing something productive in peacetime, not just training for what must not happen. Wyton, only a few miles away, had on strength three Squadrons – No 543 with Victors, No 58 with Canberras and No 51 with Comets (yes, they were still around, sound military versions not scarred by the initial disasters of the commercial Comets); all three Squadrons had peacetime operational jobs to do. Those tasks included high level photography for survey, at home and abroad, and for intelligence purposes; high level radar surveillance, for instance for tracking naval fleets; low level photography for a variety of users; recording of radio and radar frequencies; tracking and analysis of nuclear tests in the atmosphere; “listening” on all frequencies near Eastern borders (still Cold War time); the testing and evaluation of new reconnaissance equipments, be they cameras, radio, radar. Wyton’s CO was Gp Capt Derek Rake when I arrived and later Gp Capt Arthur Steele. Before Rake left Wyton, he and I welcomed Prince Philip to the Station and demonstrated to him all the features of air photography.

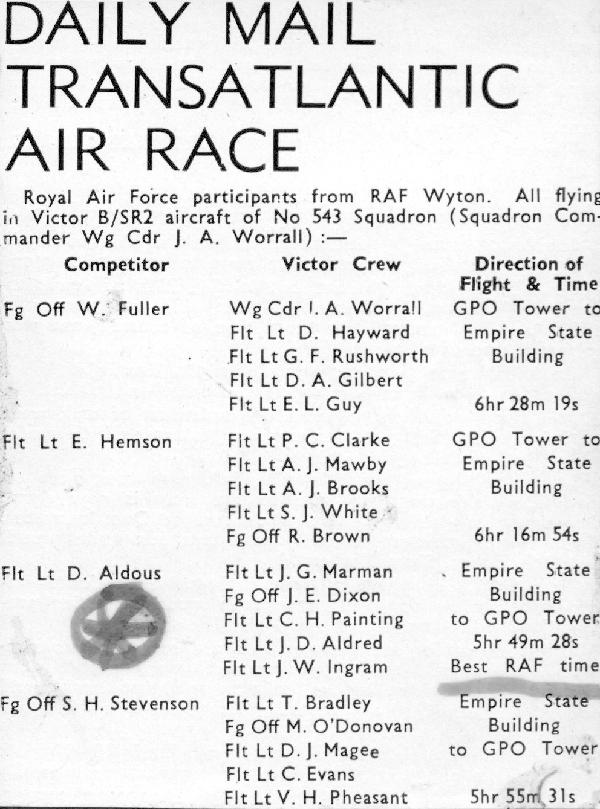

No 543 Squadron made a name for itself in another sphere of activity – the Daily Mail Transatlantic Air Race. I mentioned in the previous Chapter that the powers that be didn’t care much for the Vulcan plan. The principal RAF entry – and the fastest subsonic – was a Harrier which took off from a coaldust-blown helipad in St Pancras, was then refuelled in the air Heaven knows how many times, and finally landed in another swirl of NYC dust near the Empire State. But second fastest, in just over 6 hours was one of the crew of a Victor from No 543 which had taken off from Wisley in Surrey. I was pleased that I was able to see him off and follow his progress down in the Ops Room at Strike Command. In all fairness, it must be added that the fastest overall was in the supersonic class and was won by the Royal Navy in a Phantom heading east.

The second unit under CRE – JARIC – was co-located with CRE and was well-known in the Intelligence community, nationally and with NATO and the USA. Their principal task was that of photographic interpretation, much of it on material coming from satellite photography. The staff were tri-Service and were all experts in matters photographic and, most importantly, stereoscopy. I believe JARIC must have been one of the few units in the whole of the Armed Forces which was staffed by Navy, Army, Air Force, WRNS, WRAC and WRAF. Since, as I keep on saying, we are still very much in the Cold War stage, the work at JARIC was of vital significance. I remember on one visit peering through stereoscopic spectacles at a huge swathe of Southern Russia as big as an English county peppered with strategic missile sites. In early 1969 JARIC was commanded by Gp Capt John Hart and later by Gp Capt Jimmy Marmion, both navigators and both very good at their job.

JARIC was heavily dependent on the products of the third unit in CRE – JSPI at Bassingbourn – a small outfit whose sole purpose was to train PIs to the highest possible standard for all three Services.

So you see that CRE was unique in a way: it carried out specific peacetime tasks of reconnaissance and intelligence operations. It enjoyed direct links with much of the intelligence community in both the UK and the US. During my time there, I travelled to New York, Washington, Dayton, Columbia, Lima, Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne; and took an active part in a Norwegian mapping survey. Let me deal with each of those in more detail.

First, the US trip: it was designed to attend conferences on recon and intelligence matters at Dayton (my old stamping ground – Wright Air Development Center), then Columbia in South Carolina, the home of Tactical Air Recon Center (TARC) the American equivalent of CRE (but somewhat bigger!), and finally Washington for talks with the CIA. I was welcomed everywhere with the usual high standard of American hospitality. In Washington, I particularly remember meeting a man who was legendary in the photographic intelligence business – Art Lundahl – who not only enjoyed entry in the UK Who’s Who but was also awarded an honorary knighthood a few years later in 1975; and being entertained by him in the prestigious Cosmos Club.

As to TARC, I was asked on my return to assemble some articles from Allied Air Forces in their magazine, and to provide my own words in a foreword under the heading “This is your Voice”.

“I am honoured and privileged to be asked to write this foreword, and on behalf of my colleagues in the Canadian Armed Forces, the Royal Australian Air Force and my own Royal Air Force I send you sincere greetings. It was my pleasure a few months ago to be hosted by your Commander, General Holbury, and to be shown, with admirable enthusiasm and in a fine spirit of co-operation, the work that goes on at TARC.

When I arrived in my present appointment, the first question I asked myself was the basic one -–what is reconnaissance? – because recce as an air role has tended over the years to wrap around itself a certain air of mystique which I feel it doesn’t warrant. In its simplest terms its aim is to sense change beneath the aircraft and to produce a properly interpreted record for a Commander, the man who needs the information to make correct decisions in the right time scale.

The tools of the trade have progressed of course. Sensor vehicles have had to keep pace with the defences opposing them; the sensors themselves have spread out through the spectrum to combat darkness and weather; and each sensor has had to match the ever-increasing demands of the vehicles’ greater speed and lower height. But whatever the degree of change, the basic aim still remains the same and the aircrew, the man with his own fallible but flexible computer, will continue to be the most vital part of the system.

When we turn to the ground environment for supporting that airborne effort, today’s equipments are already far more complex then yesterday’s in order to be able to digest the sensors’ output. Tomorrow’s will reflect the the inevitability of ‘real time’, but even then, there is a constant factor – the Commander will still have to rely, for presentable intelligence, on the unique skills of the photographer and the PI.

Successful reconnaissance will always be dependent on the combined efforts of a triumvirate – the recon crew, the photographer and the PI. The second and third should never be swamped (theoretically) by the efforts of the first – one can simply apply more people and more equipments to the task. But you can’t have more than one decision-maker in a particular battle situation and I believe that one of the most serious problems in the recon business of the future is to ensure that his decision-making is not stifled by indigestion.

I send best wishes from all members of the RAF Central Reconnaissance Establishment to the readers of this magazine and I commend to their interest the articles in this issue which will give some idea of the recon efforts – albeit on a smaller scale than your own – of Allied Air Forces.”

Looking back on those words thirty-five years later, I recall that I had seen, in Washington, some evidence of “indigestion”. Somewhere in the depths of the Pentagon a young officer proudly showed me the product, on computer continuous paper, of one recon flight in Vietnam. The paper made a pile about nine inches high. I didn’t ask how it was all assimilated.

And then there was a visit to Lima in Peru. It was in mid-1970 that the French planned a series of nuclear tests over Mururoa Island in the South Pacific. A couple of the Victors of 543 Squadron were tasked with sampling the debris in the atmosphere (must keep track of our neighbours) and were fitted with the necessary filtering and collection kit. I was asked by Strike Command to forge friendly links with the Peruvian Air Force and thus was in a position to navigate Arthur Steele in one of the Victors. We flew to Lima in three hops – to Goose Bay (fishing in an isolated lake, but millions of flies), then Kingston, Jamaica (the humidity!), and Lima, Peru’s capital. At the time Peru was suffering from a terrifying “terremoto” which had torn the top off an Andes mountain and swamped a number of villages in mud. We loaded the Victors as far as we could with blankets, clothes and such like collected from the stations within the group.

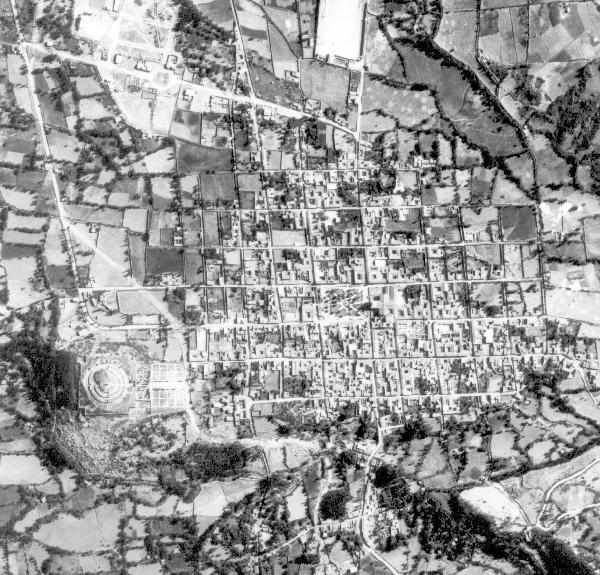

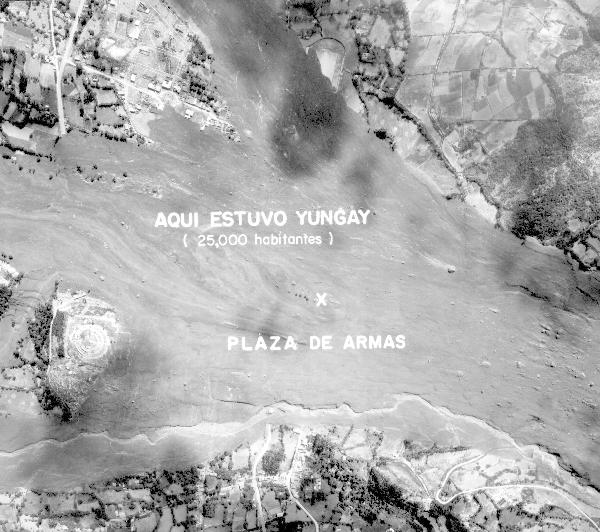

We were welcomed by the Peruvian Air Force and the local Air Attache. Gifts were exchanged and the charitable loads taken away, with grateful thanks. We stayed at the Crillon Hotel: the City’s inner affluence contrasted markedly with the poor of the City living on rubbish heaps on the outskirts – the ‘barriadas’. The contrast was as bad as I’ve seen anywhere in the world. A Peruvian Colonel showed us awesome aerial photographs comparing villages before and after the mud slides. In the one, streets, monuments, buildings; in the other, nothing visible – all smothered in the mud. Terrible. The same Colonel, whose English was quite good, drove Arthur and me up into the Andes. Lima on the coast has a weird climate – almost permanent low cloud, but no rain, ever, because of the cold Pacific current – but as you ascend inland, the skies clear, the sun feels warm (the Latitude is only 12 S), cumulus starts to build and the Andes take rain which then flows to the city on aqueducts dating from early in AD. We climbed for a long time, to just short of 16,000 feet, and passed across the highest level crossing in the world. I felt decidedly sick with lack of oxygen – our host produced oxygen masks.

Arthur Steele and I had soon done our bit – the ceremonial and the friendly. The second crew stayed on to “sniff” a number of French tests which followed over the next few weeks, and finally returned home and went through intense cleansing before releasing the results of their filtering. The noteworthy event for me on the way home was that between Lima and Kingston, our timing and route was such that we passed very close to the ‘subsolar point’, that is, the point at which the sun is directly overhead. I was thus able to obtain with the sextant a ‘solar fix’, a very unusual event which every navigator dreams about. The thoughtful officers back home at Wyton had arranged for Pat to be in the Control Tower to see us come in to land. A memorable trip.

As to Australia – well, MOD asked me to travel to Canberra to give a series of lectures on our activities, principally to the RAAF Staff College. I was flown by RAF VC10 to Singapore and then it was Qantas, via Brisbane, to Sydney. Once there I was in the hospitable hands of the Australian Air Force, who flew me to Canberra for the purpose of the visit (and I was able to get away with an Australian joke) and then took me to Melbourne and back to Sydney, where I was dined on top of the ‘Summit’, entertained by the Union Club and taken on a launch around Sydney Harbour. It’s a small world – the officer mainly responsible for my welcome was the Aussie who had been with me at Shawbury on the Spec N Course twenty years before.

The Norwegian survey job had been given us by the Foreign Office. We had a reputation world-wide for accurate flying and aerial photography used for Ordnance Survey maps. I flew a couple of times to Sola and Aalborg in connection with the project and navigated one of the 8-hour flights in a Victor producing a part of the survey.

Summarising my log book whilst at CRE, I flew 28 times as navigator with 14 different pilots, splitting fairly equally between Victors, Canberras and Comets. The Comet flights were well into the Baltic – as far East as legally permissable. In addition to RAF Wyton’s CO (Arthur Steele), I managed to fly with all three Squadron Commanders – Wg Cdrs Easterbrook, Worrall and Harper, and with my first Senior Air Staff Officer at CRE Gp Capt Ted Sismore, a much decorated WWII veteran. Ted’s place was taken later by Peter Scott. I was fortunate indeed with all my senior officers.

Meanwhile, of the family: Peter spent his 3rd and 4th year at Brunel and had become very friendly indeed with a girl called Patricia Gammans, the daughter of another RAF navigator; Peter had first met her at Stamford. Richard was progressing fast at Stamford, upgrading from Exhibitioner to Scholar, taking ‘O’ Levels, passing Grade VI at piano and playing three pieces at the 1970 Speech Day. Jonathan attended pre-nursery school in 1969 and nursery school the following year, both on the base; he was then three years old. From Brampton we were able to take a number of holidays on the east coast and on the south coast, and in view of what I was told in May 1970, we all had to check that our passports were up-to-date. In a bit of spare time I had built a dinghy-size boat with a mast and sail, all of which fitted neatly on to a roof-rack.

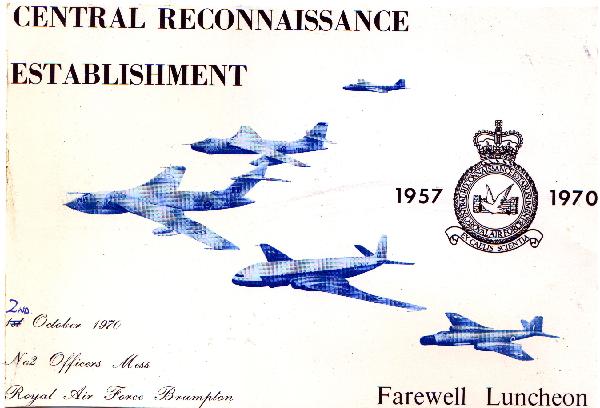

That month, I learnt two things about the future. CRE was to be disbanded and closed down on 1st October 1970, with its three units and its responsibilities taken over by No 1 Group. I was to be posted to Brussels as Secretary to the Military Committee of NATO soon after, taking the place of a British Army Brigadier. Lots to think about and lots to do. The main thing was to make the CRE closure an event. Everybody agreed – Command, C-in-C and all my own staff – that it was essential to mark the event in a memorable way. The plan was: we would have an internal Guest Night in the Mess on 25th September; and on 2nd October, we would arrange a formal luncheon with many outside guests comprising all past AOCs and SASOs, senior people from Strike Command and No 1 Group, and relevant officers from the MOD – mainly operations and intelligence. The line-up meant that the most senior guests would be our C-in-C Sir Denis Spotswood and the big wheel in the Intelligence business Vice Admiral Louis Le Bailly. [Reminds me to observe that that hoary old joke about the phrase ‘military intelligence’ being an oxymoron wears a bit thin!] And the really nice thing about the line-up was that Gp Capt (Retd) ‘Ting’ Ring from Waddington days would be there as an ex-SASO of CRE.

Before either of those events took place, there were other speaking engagements to undertake: Wyton Officers, Wyton Sergeants, JSPI at Bassingbourn; JARIC would be included in our Guest Night at their Mess at Brampton. That was the 23rd September occasion. It was a boisterous evening, the last occasion when I would have the opportunity to chat to many of my loyal staff. There are many names I haven’t mentioned, but two particularly stand out in my memory: Sqdn Ldr Ken Cater (from Southend!), my Engineering Officer, who was bound to pick up the nickname “Forni”; and Wg Cdr John Hall, a wizard on cameras and everything photographic, with only – would you believe – one eye! At the end of the evening of that last Guest Night, I was towed away from the Mess in a contraption labelled the “Mark II Eyeball Transporter”. The point was that we all referred to the recon man’s eyeball as the final sensor, but the Mark I was the Untrained Eyeball.

On the final day of CRE’s existence, I received the following telex from CAS: “on the reallocation of the functions of the Central Reconnaissance Establishment I would like to express my appreciation for all that you have achieved in maintaining the high standard of reconnaissance in the Royal Air Force. The outstanding reputation which CRE has gained over the years has reflected great credit on the professional ability, zeal and foresight of those who have worked there. My congratulations on a job well done and my best wishes for the future to you and all the staff of CRE.” And from ACAS (Ops): “On completion of your task at CRE I would like to thank you and all the staff for your help and cooperation. The results which you and your predecessors have achieved have earned the respect and admiration not only of the Royal Air Force but also of the many Commonwealth and Foreign Air Forces with whom you come in contact.”

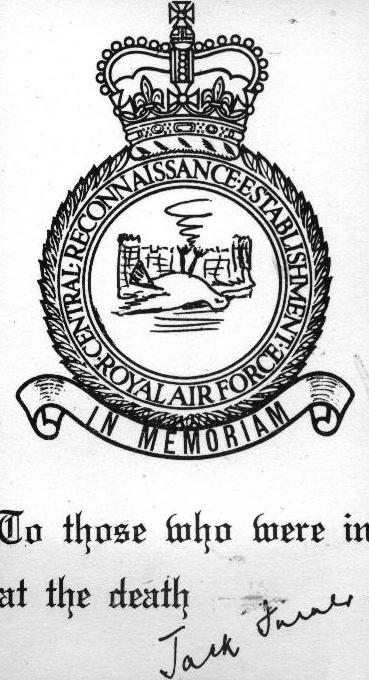

On 2nd October we were all on our best behaviour to welcome to the JARIC Mess all the bigwigs and past CRE staffs so that we could close down the outfit in style. The crest of CRE bore the motto “Ex Caelis Scientia” (Knowledge from the Skies) and showed a dove flying in front of a wall. One of the wags on my staff had produced a new version: the motto was “In Memoriam” and the dove had expired, lying on its back with its legs in the air; I signed a number of copies under a subscription “To those who were in at the death.” It was all taken in good part. In any case, I had made sure that one of our Canberras had gone out one day to photograph the C-in-C’s residence at “Springfield” near HQ Strike; in presenting it to him on this occasion, I asked him not to enquire further into how we obtained it. (The area is subject to very tight restrictions on low flying.)

So much then for CRE. All of us dispersed to far corners. My family and I were soon off across the Channel again.