General Ed Rowny in his flattering piece of departing verse referred to the UK’s inflation and a new home. It seems strange perhaps at this distance to be making reference to one particular facet of the UK’s economy, but our country was off on a wild chase of prices and incomes. Mindful of the need, when we returned to the UK, to be ready with a deposit on the first house of our own (I was now 51), we had been trying to save a bit of my salary; it wasn’t much, but it was a start. And all the time we were saving, inflation was taking off and a typical house price was increasing per year at a faster rate than we could save. This was unfortunate.

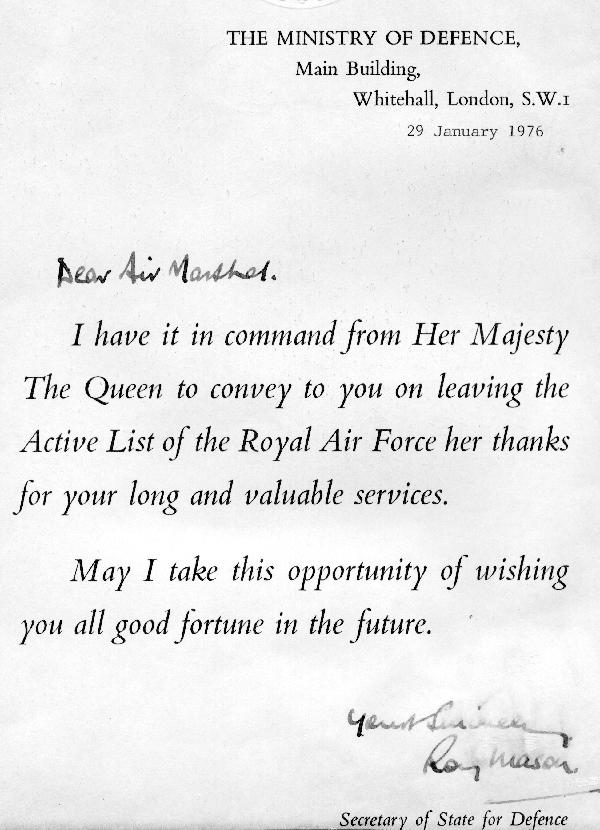

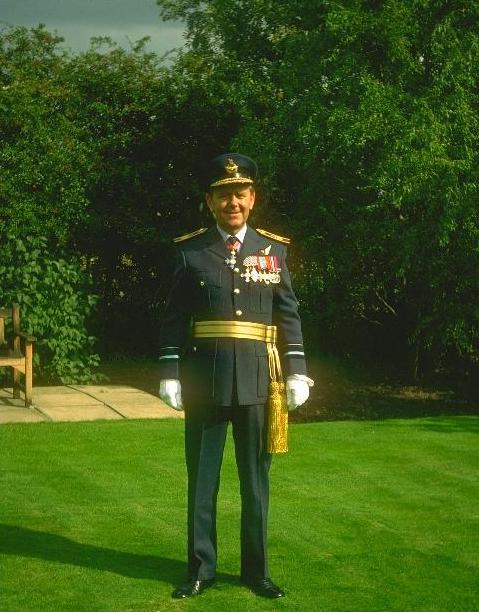

Whilst still in Brussels I had been studying the UK map and looking at house prices at one hour’s distance from London. We settled for the Huntingdon area, which we knew well from the CRE days, and I travelled across before posting to select a house in the suburb of Huntingdon known as Hartford. We, and the Building Society, bought the first home of our own – our 24th – at 12 Pennington Road. It had 5 bedrooms and two bathrooms and a nice garden, but it needed a lot of decorative work. The previous owner was a doctor, who didn’t seem too fussy and who left a pile of broken phials in the middle of the garden. Brother Ken, who by this time had built up a very reputable and prospering wallcoverings business, came with me to look the place over and agreed with me that it was good value in terms of £s per square foot.

The final departure from Avenue Colonel Daumerie was a trifle fraught. We seem to have collected rather more belongings than we had arrived with. Both the Jaguar and the caravan were stuffed to the gills; the caravan, in particular, was filled everywhere – on the floors, underneath the beds – so much so that I wondered about the springs. We took it gently down the autoroute to Ostend and from Dover to Huntingdon. Pat took one look inside the house and – I knew it was coming – “Oh no – not again!”. We employed a local decorator who did a very passable job for a couple of weeks painting here and there and putting up many of Ken’s wallcoverings (one of them upside down which we just spotted in time); and we recarpeted the whole of the ground floor. Thus was this first real home belonging to us brought up to scratch.

It was now late February 1973. Edward Heath was Prime Minister and he had just signed the United Kingdom into the European Economic Community. Unfortunately he was riding for a fall which would occur within a year.

Peter was 24, working at IBM as a systems analyst, and had set up home with Tricia in the Croydon area. Richard was 18 and, having obtained 5 very good ‘A’ Levels, had entered Cambridge (Churchill College) reading Maths. Jonathan was 6 and was attending at Hartford School which was within walking distance. I had to drive to Huntingdon Station to catch the train for London every day: which brings me to the work.

You may recall that when I became a Deputy Director in the MOD in 1965, I followed a chap called Dougie Bower. It seems that the two of us made a wee bit of history for navigators in February 1973. He and I were both placed in AVM jobs: we were the first navigators to get there. Headlines in some of the press read “Navigators reach the top” and “Navigators step higher up promotion ladder”. Bower went into the post of Assistant Chief of Air Staff (Operational Requirements) – (ACAS(OR) for short); and I was placed in a new post called Assistant Air Secretary, working again in my old stamping ground at Adastral House, Theobalds Road near Holborn. It was a strange title: the job was a mix of part of the old Director-General of Manning plus much more. In fact, I had two masters as I shall explain in a moment. First I should mention that the term “Air Secretary” had been around a long time – he was at least a 3-star, often 4-star (Air Marshal or Air Chief Marshal) – whose prime responsibility was to plot the postings and promotions of the very top officer ranks from Air Commodore up. He had to have very senior rank himself in order to be looking down from the top at the material coming up the ladder; spotting future Chiefs of Air Staff was a delicate business, but so vital for the general health of the Service. Even when you’re sure you’ve got it right, one individual, outstanding in all respects up to that point, can wreck the progression by a stupid lapse of behaviour – as happened, sadly and to consternation in the RAF Club, some years after my retirement.

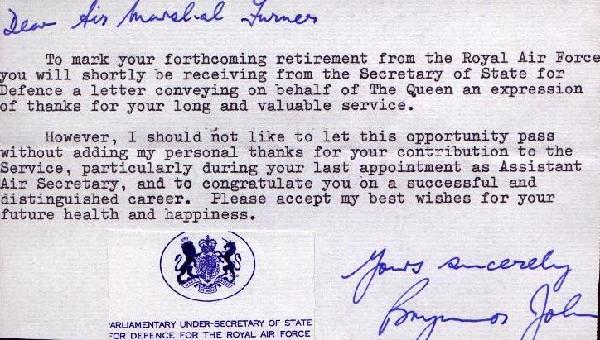

Talking of lapses of behaviour, I should mention that one of my first duties on returning to the MOD was to go to Whitehall to say hello to the then Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State. He was a Viscount and I shan’t mention his name. I didn’t like him – he struck me as effete. He was disgraced by some scandal only a short time after the interview and resigned.

Anyway, the “Assistant Air Secretary” was a new post and I was to look after all aspects of officer management from Group Captain down. In the first place I supervised and co-ordinated the efforts of three Directors who were directly responsible to me – Director of Personnel Air, Director of Personnel Ground, and Director of Personnel Plans & Policy. The first two managed the GD (Flying) Branch and the Ground Branches respectively in the following spheres: appointments, promotions and career patterns, selections for post-graduate training, careers advice, retirements and resettlement advice. The third Directorate was responsible for all aspects of officer manpower planning: matching strengths to establishments, the planning of career structures and ‘ideal’ career patterns, conditions of service, promotion quotas, quotas for intakes, assimilation, extension and premature voluntary retirements, manpower forecasting for ten years ahead, into training and into/University recruiting targets and all aspects of manpower statistics.

The odd thing was that I myself had two masters. The activities of my first two Directors, which centre on the individual, were Air Secretary’s type of work. Whilst the Air Sec was concentrating on the Air Ranks, I was looking after the rest of the officer corps (about 18,000 officers then) and was responsible to the Air Sec for that work. The functions of the Plans & Policy Directorate concentrated on the whole rather than the individual and thus fell into the interests of the Air Member for Personnel, an Air Force Board member. It was to him that I answered for the latter functions. Thus it was said that the new post of Assistant Air Sec focussed in one officer the two broad areas of work: the career management of individuals on the one hand and the manpower planning of the whole officer cadre on the other. So – two masters – Air Sec and AMP. It didn’t make life easy. I made it work, because one had to, but I felt all the time that there had to be a simpler way. There was; it evolved later.

From all of this background, I can now list a number of detailed matters of authority vested in the position of Assistant Air Secretary. For instance:

Determining ways and means of employing officer resources in the most cost-effective way possible, having regard to the essential needs of the Service on the one hand and to the aspirations and expectations of the individual on the other;

Ensuring that the quality of personnel management, in terms of the individual, was maintained at an optimum level;

Keeping under constant review, particularly in an era of pressures on defence budget expenditure, the parameters of the overall officer structure – intakes, wastage rates, promotion quotas, probabilities and average ages;

Formulating and adapting personnel policies and conditions of service to keep pace with the changing scene;

Authorising the promulgation of promotions at the middle levels and presiding personally over the affairs of Promotion Boards concerned with Group Captains;

Presiding also over the affairs of Selection Boards for a number of mid-career training courses.

The two masters at the time I arrived in the MOD couldn’t have been more different. The Air Secretary was Air Chief Marshal Sir John Barraclough, a very shrewd gentleman indeed. He was one of those slightly disconcerting persons whom you felt was way ahead of you as you were explaining some point of policy or practice. I had known him before, at High Wycombe and when I was at both Scampton (he assisted hugely with the Strike Command ceremony) and Brampton (he hastened my quarter along). So we weren’t strangers; it proved to be most stimulating working for him. I remember I had the temerity one day to question his use of a capital letter after a colon: I think it’s an American usage – he attended the Harvard Business School way back.

The Air Member for Personnel (AMP) was Air Marshal Sir Harold (“Mickey”) Martin, famous as one of the “dambusters” in 1943 and now right at the top as a member of the Air Force Board. Frankly, he was a bit out of his depth. Terrific chap, good leader, but if I were talking to him about the geometry of career structures, I could see his eyes glazing over and I could imagine him wishing we were having a pint at the Club instead. He is no longer with us: he died in 1988.

Both of those officers were replaced in 1974 and I therefore had to get used to two more masters. After all of us working in Adastral House had dined out Sir John Barraclough (he was the last to leave the Uxbridge Mess – I had to drag him out at dawn) Air Chief Marshal Sir Derek Hodgkinson took his place. He was well-versed in our work for he had written a special in-depth study of the GD Branch a few years before. We got on fine together. When “Mickey” Martin retired from AMP, a very fast-running officer indeed took his place – Air Marshal Sir Neil Cameron – who had been at SHAPE as a Group Captain at the same time as myself. His eyes never glazed over. When I retired two years later, he went on to Chief of Air Staff, then Chief of Defence Staff (because another RAF heavyweight Humphrey had died), then ennobled – a very sharp officer indeed. Sadly, he died in 1985. His autobiography – “In the Midst of Things” – was published posthumously.

A strange thing happened when I first arrived. I was invited down to Whitehall, the main building of the MOD, to have a “chat” with a couple of AVMs – John Aiken and Alan Davies. The latter was ACAS(Policy) and Aiken had at that time a roving assignment to take an overall look at ways and means of running the RAF on less money; that’s how it was then, always had been since WWII and probably always will be. Anyway, these two obviously wanted to push a particular thought into my head right at the start. They decried the manpower calculations over the previous few years, declaring that there had to be significant cuts in the “Into Productive Service” (IPS) intake of under-training pilots and navigators. I couldn’t resist a wry smile: precisely what I’d been impressing upon everybody back in 1966/67. “There are too many ground posts for GD officers”. (Well, well! – see the Establishers). “Think how much it costs to train a pilot or a navigator”. (Ah yes! I remember it well!) I assured them they didn’t have to worry – I knew exactly what they were talking about – the problem would receive my urgent attention, etc… Funny how some things go round in circles. One of the first things I did was to ignore a vast Committee which I was supposed to chair every so often. It was called the Officer & Airmen Aircrew Manning Committee and I had seen it in previous years going on and on and getting bogged down in detail. I preferred to circulate papers to interested parties, chosen as appropriate, and asking for approval or comment by such and such a date. If there had been no reply by that date, I took that as concurrence. “The ideal ‘committee man’ does not make his associates uncomfortable; he does not operate with ideas too far outside of what is generally accepted. Thus the thrust of committees is toward a standard of average performance.”(Henry Kissinger.)

Or, to quote my favourite saying on the matter – “When in doubt, never commit yourself; always committee yourself.”

Certainly those two AVMs – Aiken and Davies – had given me the right pitch. I’d have pursued the path they were commending whether or not we had had our “chat”. It was not one of those problems where you come up with a solution just like that, but a long haul involving visits to all the Commands both at home and overseas in order to get people appreciating the means and the aim. It was to get to a virtuous circle situation: cut ground posts for junior GD officers, cut the IPS required, cut the training organisation, cut the establishment of qualified flying instructors, cut the IPS still further, and so on. It took years afterwards to get anywhere with it, particularly bearing in mind that the training pipeline is two years long. Add to the general problem the fact that, at the end of the two years, the politicians have had another go at cutting the front line and you can see that flexibility is the buzzword. [I was told after I’d retired that for a year or so they were really scratching around for junior officer flyers – somebody had been putting the ground jobs back again! And whenever George Kemp and I – he was also an AVM, looking after all aspects of manning and careers for airmen – go to retired briefings, we wait for the inevitable comment about too many ground posts.] I had a large printed banner in my office “You Can’t Have it Both Ways.”Ironically, the politicians were also doing their best to reduce our recruiting targets by constant cutting of the front-line establishment, a process that seems to have been going on ever since Korea. [And is still going on at the turn of the Century.] Hence much of my time at the MOD on this tour was concerned with the painful business of redundancy programmes. In 1974/75 it became so serious as to demand an element of compulsory redundancy as well as voluntary in order to achieve a manning balance. This was a sad and difficult task, but very carefully monitored at all stages: from each file of confidential reports, there had to be no doubt that we were weeding out the weakest in the interests of the Service.

I used to travel up to Kings Cross from Huntingdon with a very amiable chap called Eric Cook – AVM, Director General of Training – and we would walk from Kings Cross to Theobalds Road – very good way to get in form for the day. Our returning times did not often coincide, but I still walked back to Kings Cross in the evenings. I remember leaping from the train at Huntingdon station one night and I misjudged the platform: I was in the last carriage and with my left foot I hit the initial incline instead of the flat bit. There was a horrendous crack – my Achilles tendon had gone. I limped to the car and drove home pressing the clutch with my left hand (try it!), called the Doc at Brampton, who shunted me straight off to Ely RAF Hospital. They had to operate and put the tendon back together. I was in there for a few days and it was somewhat embarrassing having to cancel various events because of “wanting to get home quickly”. Whilst in Ely, just for the heck of it, they thought they’d check everything else. They took chest X-Rays twice (I was still smoking) and then asked for a third. This wasn’t doing my morale any good, but on the third occasion they put a metal ring around my left nipple. Ah-ha! The nipple was what had been confusing them. So it was nice to know that there was nothing else there. I came away from Ely with a yard length of plaster cast which had to stay for about six weeks and made life rather more difficult than usual. HQ Training Command at Brampton kindly put one of their staff cars at my disposal so I had the pleasure of a drive down and back on the A1 every working day until the cast was removed. One day during that period I was due to appear at Training Command to give them all a lecture on what we were trying to achieve. Some wit in the HQ had prepared an Operation Order – “Hump the Air Marshal” :

AIM – To deliver one Air Marshal from the entrance of HQTC to the AOA’s Office intact. MODUS OPERANDI – 10.40 Wheelchair in AOA’s office; 10.45 Meet patient at entrance & lift to AOA; 10.55 Wheel to Conference Room; 11.20 Wait in small conference room; 11.30 Lift back to car

(signed) W.E.CANDOIT, VIP Carriers Ltd

This was about the time when the economy was causing nothing but doom and gloom. Prime Minister Heath had had a row with the miners over pay and conditions, and at exactly the same time the price of oil had been quadrupled by the OPEC countries. Instead of wiping the slate clean and declaring that we now had a completely new situation and let’s sit down and talk about it, Heath decided to call an early election on the basis of – “Who governs?” It was a disastrous decision. The run-up to the election was made appallingly gloomy by the three-day week: Heath lost and handed No 10 back to Harold Wilson. Wilson, ever the opportunist, decided to increase his slim majority with a second 1974 election in October. In the run-up to that one, I well remember Denis Healey, who had changed from an admirable Defence Minister to a mean Chancellor of the Exchequer, taking the latest quarterly reading of the RPI increase as 2%, multiplying it by 4, and triumphantly announcing an annual rate of 8%. By the following year it had reached 27%.

The Retail Price Index (RPI) statistic had been worrying the Civil Service – in the interests of the country, of course, but also in respect of their pensions. In the early 1970s they had convinced their political masters that their pensions should henceforth be index-linked. By “their” pensions they referred to all public service pensions; hence the agreement to index-link affected millions of people – civil servants, teachers, doctors, firemen, you name it – and the Armed Forces. I remember a paper making the rounds in the early days of my tour as Assistant Air Sec and seeking comments. I pointed out that across-the-board index linking for the rest of time would produce an ever-increasing spread between the lowest and the highest; I counter-suggested that the percentage used each year should be tailed off by some suitable formula towards the top end, and boosted similarly towards the bottom end. The fact that my suggestion was ignored has been very favourable to my standard of living since retirement. [It will be most interesting to see what the Government of the day will do if, at some time in the future, the deflationary conditions of the 1930s return.]

Apart from visits to Commands, other trips out of the office came my way. I was asked twice to be Reviewing Officer at RAF Henlow in order to welcome newly graduated officers and to present on each occasion the Sword of Merit and other Trophies. It was always a pleasure after the formalities on the parade ground to talk to the young officers and their families informally over a drink.

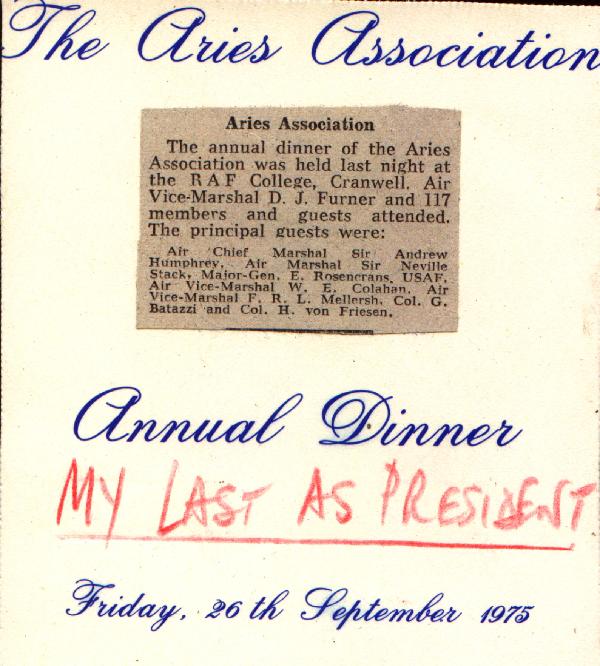

Then there was the Specialist Navigation Association which I had been keeping in touch with over the years. Because of a change of name of the course the Association now held the title “The Specialist Navigation and Aerosystems Course Association”. When I arrived at MOD in Feb 1973 Air Commodore John Mitchell, who had been President of the Association, wished me to take over that Presidency, and I was pleased to do so. I set about changing its name. Apart from anything else, it was pretty stupid asking members to write out cheques made out to “The Specialist…etc…..etc….Course Association”. I put it to all members “Would you like to change the name to “The Aries Association”? (The first point of Aries having vital navigational significance.) The response was overwhelmingly in favour. The Aries Association it has been ever since. I was fortunate to be able to chair three annual dinners of the Association at RAF Manby. We had as principal guests Professor R V Jones of “bending the beam” fame; Vice Admiral Sir Louis Le Bailly, lately of Intelligence; and Air Chief Marshal Sir Andrew Humphrey, CAS, whose untimely death soon after presented the Air Secretary with a sad problem.

In any Service there are thousands of printed forms. An RAF Form 295 was a good one – leave chitty. A Form 252 was a bad one – you’re on a charge! The Form which occupied Personnel staffs more than somewhat was the Form 1369 – the Officer’s Confidential Report – that is, an appraisal report. There were four pages of foolscap size to it. A page and a half was taken up with tables from 1 to 9 against various headings: Initiative, Leadership, Sense of Duty, Man Management, and so on, about two dozen such marks in all. It was a form not to be taken lightly. To complete one fully, fairly and satisfactorily would take a good couple of hours. An accompanying legend would provide a guide to performance under each heading and against each mark or range of marks, but the difficult and sensitive task of the assessor was to make the correct judgment. After all the individual markings, the Form called for one overall figure out of 9 for suitability for promotion. Then would follow a paragraph describing the officer’s character and performance in words by the assessing officer, and space for further comments at higher levels of command – up to another three. Such a form would of course give rise to humour. The following comments are almost certainly apochryphal: “Men will follow this officer – if only out of sheer curiosity”; and (undoubtedly borrowed from the Cavalry): “I would not breed from this officer”. One subject was not provided with the full spectrum of 1 to 9 – drinking. There were four squares (2 x 2) which would allow drinking habits to be described as “wisely” or “unwisely” and “occasionally” or “frequently”. You will readily see that it would be possible to mark two squares. Alongside – and there’s something very significant about this, perhaps – was a solitary square “Does not drink”. One doesn’t see one’s own reports, but I’m willing to bet I never had that one filled in!

Anyway, the Form was of fundamental importance in managing the officer corps. Every officer had to have a 1369 raised on him at least once a year, and on posting. The forms thus gradually collected on an individual’s file and would be available to Promotion Boards (or Redundancy Boards). I’ve mentioned above that it was my personal task to preside over promotion to Group Captain. Other members of the Board would be called in from outside the MOD, rather as civilians are called for Jury service. Our task, for instance in the GD Branch, would be to select some 12 to 16 (depending on quota) for promotion from Wing Commander to Group Captain every six months. Some would be younger, fast runners; some would be average runners; some would be older, perhaps being promoted only for their last tour prior to retirement. If you were to promote only fast runners, then you’d block the structure for years to come. But all of them would have to appear promotable from the 1369s. We’d examine every 1369 on each candidate for promotion: I’d call for a mark out of 9 from each Board member and we’d make a total. If there were a greater spread than 3 between members on any one candidate, I’d wish to discuss those differences until we could more nearly approach a consensus. I would have some of my own staff there, monitoring the Board’s progress. They and I would be able to warn of any marked differences in marking criteria. We would know of assessing officers who tended to “hardness” or “softness” in marking. We could help to even out subjective opinions.

It was truly as meritocratic a system as one could devise. There was always scope for improvement: I made some changes to the form whilst I was there and was asked to record on video a short instructional talk for use in the RAF Staff College curriculum at Bracknell. During my time, a number of large Companies expressed interest in our methods of appraisal and promotion.

I recall that it was Monty who first spoke humourously of officer qualities. He would take the two yardsticks of intelligence and industry and postulate four extreme combinations. The intelligent and lazy would make the best commander because he would sensibly delegate. The intelligent and industrious would make the best staff officer – he would beaver away to best effect. The stupid and lazy you could ignore – just post them to the middle of the Indian ocean or somewhere. But the one you really had to watch was the stupid and industrious – and don’t we all know them?Now the fact that a navigator rather than a pilot was doing this work in the MOD excited no particular interest – it was nothing to get excited about. However, funnily enough, the Americans did. There was a Service magazine over there in the USAF called The Navigator and in 1975 they took a close interest in what was going on in the RAF. The Editor asked me for a lot of facts and figures and here is what the magazine made of them:

“Initial recruitment and junior officer strengths in the RAF are in an approximate ratio of two pilots to one navigator. Promotion to all levels is based solely on merit. Officers compete before promotion boards without differentiation as to category. Current strengths in grades of squadron leader and above show pilot-to-navigator ratios as follows:

Air Vice-Marshal 15 to 1

Air Commodore 11 to 1

Group Captain 5 to 1

Wing Commander 3 to 1

Squadron Leader 2 to 1

Posts open to navigators at squadron leader level are Flight Commander and Leader posts in V-Force, Transport, Nimrod, Buccaneer, Phantom and Canberra Units. At Wing Commander level, navigators may command squadrons and serve as OC Operations Wing in some areas. At Group Captain level, RAF policy provides that single-engine aircraft stations require pilots in command. On the other hand, a station such as RAF Finningley, at which navigator/AEO training is conducted, is almost invariably commanded by a navigator. Between these two extremes, navigators may be selected on merit for command at non-single engine type stations.

The career of Air Vice-Marshal Furner, a navigator, serves as an illustration of practice in the RAF. His assignments have included OC Ops Wing on a bomber station, Station Commmander of a bomber base and Air Officer Commanding Central Reconnaissance Establishment, en route to his current high post as Assistant Air Secretary. As he puts it, Equal careers, equal opportunities, works in the RAF. “

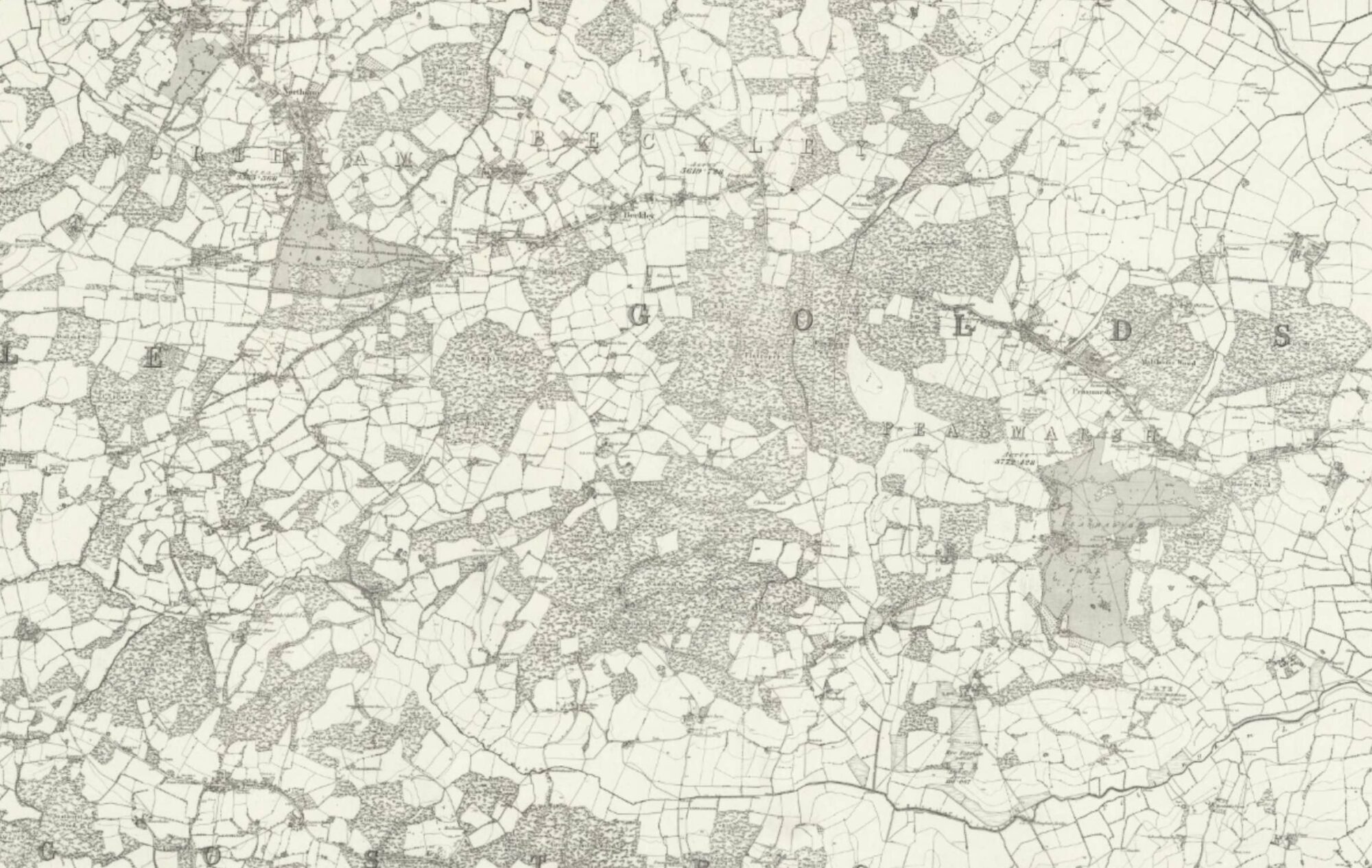

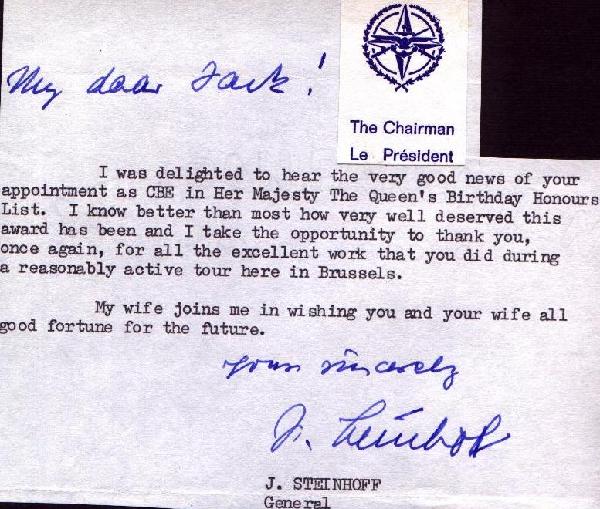

There had been a nice surprise in the middle of 1973. It seems John Read in Brussels had put me up for a CBE, so Pat and Jonathan accompanied me to the Palace again. On this occasion it was the Prince of Wales who was doing the honours. Thus all three boys had now visited the place, which was very neat. Mind you, I had to return the OBE subsequently which seemed a bit mean. Both Steinhoff (Military Committee) and Goodpaster (SACEUR) were good enough to write. And on the first day of 1974 my acting AVM had been made substantive.

There was a lot going on with the family during this period. Peter was beavering away at the giant computer company IBM; Richard completed his second and third years at Cambridge and published a couple of BrainTeasers in the Sunday Times; and Jonathan was progressing fast – and really fast – at Hartford School. Pat and I took Jonathan on a couple of very pleasant holidays to the Lake District and the West Country: in the meantime, we had the caravan parked in a Wyton hangar which was very convenient. Pat’s sister Betty and her Finnish husband Simo decided to emigrate with their daughter Anna to South Africa. Simo had stars in his eyes as to how prosperous he would be out there.

But the saddest family event was the death of Elsie, my mother, a few days before her 75th birthday in April 1975. She was the first of four siblings to go. She had had a hard early life but had been happy with John Franklin since the war.

Alan Clark, my old school friend, with whom we had kept in touch over the years, had asked me in 1973 to officiate at his school (Ocklynge, Eastbourne) as the prize giver and speech maker on Speech Day. He had been Headmaster there for many years at a school for 7-11s, and in accordance with his constant wish to raise standards he had decided to introduce the Secondary School idea of Speech Days. It started a trend. I returned to the School every fourth year from then on – 1977, 1981 and 1985 until he retired – the years between the Olympics and the World Cup, as he put it.

But it was my brother Ken who, out of the blue, was to cause my life to take a totally unexpected turn. Naturally, as 1975 progressed, retirement was in my thoughts from time to time. My normal retirement date would have been 14th November 1976 (55th birthday). Since I had now been in the Assistant Air Sec post for nearly three years already, it seemed obvious that I would see out my time there. In Southend, Ken had been prospering with his Company “Harlequin Wallcoverings Ltd”. One day in November 1975, he invited me out to lunch. During a splendid meal in one of his favourite restaurants, he showed me spreadsheets of forecast figures of income and expenditure. I was suitably impressed. He asked me whether I could take over as soon as possible as General Manager – he needed somebody urgently whom he could trust to oversee the whole operation. I was excited about the idea, but was concerned about the attitude of the Service, which had been good to me, and about the problem that the Air Sec would have filling my post at such short notice. I said I would look into it; on that basis, we agreed a salary.

Ken had presented me with a very difficult decision. I would have been delighted if his offer had come a year later, but I could sense that he foresaw the imminent expansion of his business, and if I couldn’t respond quickly then he would reluctantly look elsewhere. One thing was certain – Pat and I couldn’t live on the RAF pension alone, particularly having just undertaken a mortgage. It was therefore vital to secure some employment after the RAF. Here was a post I would obviously be able to cope with, in circumstances which were very attractive, working for one’s own brother. So I talked it over with the Air Sec (Hodgkinson); he agreed; a man I knew well – Alec Maisner – could take my place and thus earn himself the rank of AVM which he would not otherwise have enjoyed; the Air Sec and I parted amiably and wrote each other the necessary formal letters. My retirement date was to be 31st January 1976, just over two years since substantive promotion and only nine and a half months prior to the statutory date. Thus did my RAF career finish. It had been a long haul from AC2 in May 1941 to retirement as AVM in January 1976, and with a lot of memories – most of them good ones. My whole adult life had been spent in the Royal Air Force and I had no regrets. Only one short period, at Middleton St George, had been somewhat wretched; all other periods had been both challenging and rewarding. The essentially good features of the life had been:

the extraordinary variety of activity, both in flying and on the ground;

the close comradeship, all working to a common purpose;

the sense, which became automatic, that the good of the Service came first;

the reliability of those around you and responsible to you in fulfilling their tasks.As to details of the flying, my log book told me that I had flown just about 1,200 times in 42 different types of aircraft with 243 different pilots, without serious incident. That says a lot for the standard of training of our pilots (and those of the USAF).

There were downsides of course. The life was hard for families: wives would sometimes have cause to worry – about the flying, about frequent moves, about enforced absences; and children of secondary school age had to attend at boarding school for their education – there was no other way. I had been fortunate. My dear wife had put up with a lot but she had always smiled her way through and always been popular with colleagues and subordinates. Indeed, without her unstinting support, I might not have reached the rank I achieved.

Oh! and one thing more – you don’t get rich in the Armed Forces! But that’s not what we joined for. As I have said so many times in speeches to all sorts of different gatherings, the Royal Air Force is the only Air Force in the world which does not have, and does not need to have, the name of its country in the title. That is something to be proud of; and being part of it is something for the individual to be proud of. I trust I shall not live to see a time when the word “Royal” has to be removed.

I was now 54 and about to begin another career in “civvie street”.