Retirement from the Armed Forces after 35 years is rather more than a routine change of jobs. It is akin to a geological fault-line. Gone is the sense of belonging to an organisation one admires and respects; gone is the cover and protection that that organisation provides for its members; but gone, too, is the sometimes daunting feeling of duty and responsibility. Now into place come new concerns: where are we going to live, how shall I perform in a “civvy” environment, how will the finances work out?

Before enlarging on any of these, one very sad thing I haven’t yet commented on is that my dear wife Pat had medical confirmation during our lives in Huntingdon that she was suffering – and indeed had suffered for some time – with Raynaud’s disease and Scleroderma. She had always experienced cold hands and feet. Whilst at Huntingdon the symptoms became very much more marked. Her hands, particularly, would swell up, turn blue and black and be very painful. Ever since those days, she has been mindful to protect herself from the cold: as I write, that is from 25 years ago. When I say cold, that doesn’t mean the same thing to her as it does to the rest of us: her hands can be cold in a temperature of 60F on a June morning. As to the Scleroderma, at the time it was a new word to me. I got the shock of my life when I looked up the word in the Britannica. 70% of Scleroderma sufferers would die within five years. Well, thankfully, she’s still here. Scleroderma starts off as a tightening of the skin – which Pat has – and later, with some, it develops to affect vital internal organs, and that’s the serious phase. Pat’s condition is stable, and for 25 years she has not developed the more serious stage. She has been kept warm with efficient heating systems at all our further addresses, rarely turned off at any time of the year.

So – the house, money, the job. We had to move from Huntingdon to somewhere in Essex – Ken’s Company was based in Hadleigh. In late 1975, shortly after the MOD had agreed to my (slightly) early retirement, Pat and I had been scanning Essex estate agent lists for a suitable home and using weekends to visit shorter versions of those lists. The lists were irrelevant. We saw a discreet For Sale sign quite accidentally in the village of Stock: I stopped the car, took one look over a high wall, returned to the car and said to Pat – “This is it.” It was in a private development of three houses. The builder of the three was selling his. It was No 2 High Trees. Our first view of the front of the building confirmed my opinion. It was of unusual and beautiful design; it was only about eight years old; leaded lights were an attractive feature of all the windows; it had a large garage for the car and a separate, very high, garage for a caravan (!); it had a garden of about one-third of an acre stocked with many trees, large lawn, flower beds, vegetable patch, fruit trees and greenhouse. Yes, indeed, this was it. It was to be our 25th home together.

Later we would learn that it had pretty horrendous condensation problems (no double glazing) which was surprising in a house a builder built for himself.

It turned out to be slightly more in price than I thought we could cope with. I cashed in a small element of my RAF pension in order to top up the proceeds from the Huntingdon sale and the RAF retirement gratuity. (A mistake – I should have arranged a loan.) Another mortgage completed the total sum and thus we started to live in Stock with no other capital. This brings me to money. One didn’t give money the attention it deserves in the Service. There really wasn’t time to think about it. Salary was a plus each month: expenditure was minus and hopefully equal each month. In other words, in Micawber’s arithmetic, a neutral situation. We hadn’t been paid generously in the Royal Air Force. I remember the year (1968) when I was in charge of a Station with 6,000 inhabitants, 24 Vulcans, 24 stand-off Blue Steel missiles and 24 megaton nuclear weapons, my “take-home” pay was just over £3,000 (about £30,000 in 2001); and although the gross figure was higher than the year before (of course), the net was lower because of more stringent taxation. But then, as I’ve already said, you don’t join the Services to make lots of money.

Now, in early 1976, it was imperative to maximise income. Ken had already undertaken to match my retirement salary, which was good of him – I think he agreed to pay me a bit more than the job was worth; to this I could now add a modest RAF pension. I say modest: it was based on 80ths. But not for one’s whole service – only from the age of 21. So – from age 21 to age 54 equalled 33/80ths: ironic, that, when you consider that I was still 21 when I had finished my first bomber tour. Still, there we are: we would be comfortable – despite the “squeezing till the pips squeak” which the then Chancellor was inflicting on the electorate. (In the year 1978, my middling income had to surrender 41% to Income Tax and National Insurance, ie not counting VAT, rates and customs duties.)

So to the job: Ken had laboured for many years to build up a wallcoverings design and wholesale business and had succeeded in making his name – “Harlequin” – well-known at the higher end of the market. At first, he had imported from many different countries – mostly European – and put together sample books with different themes, placing them in some hundreds of retail outlets. Then he went further – to have his own designs made (by Storey Bros in Lancaster) for sale not only within the UK but also for export to some 20 countries around the world. This was a bold move which changed the whole complexion of the Company and in a sense balanced up the transport arrangements, now both in and out, and the currency transactions, ditto. His first effort for export had just begun when I joined him. The collection was known as HV77 – Harlequin Vinyl valid to 1977. And he went on from there – imports continuing, exports rising.

It became clear soon after I had joined him that larger premises than those in Hadleigh were necessary. We chose a vast hangar-size warehouse in Shoebury at the far southeastern corner of Essex. I remember we plotted the whole concept with Lego blocks: racking for panniers, three high; works area for pick and pack; open plan office area for the three-way administration – orders, transport and accounts.

What I was supposed to be doing in all this gradually evolved. From Assistant Air Secretary in the Ministry of Defence I had now become a sort of S/Ldr Admin. I found myself keeping notes on what I had told staff to do. There was no rancour, nothing like that, it’s just that they needed reminding; and my smoking increased, which wasn’t good. Within the first 6 months I was able to construct a job description for myself. This is how it looked:

Oversee general running of Head Office with its three Departments and General Office. Determine and update all Head Office internal procedures.

All following items not delegated.

Personnel: Determine personnel establishment (40). Issue contracts of employment. Within overall budget set by the Board establish pay levels and differentials. Calculate overtime rates for weekly paid. Calculate salaries for monthly paid. Pay IT/NI monthly. Implement T & N pension scheme.

Stocks: Retain all stocks at necessary levels and compile orders. Calculate stock values monthly. Organise stock checks as necessary. Release export orders of Harlequin Vinyl, Flock and Hessian. Design optimum use of stock warehouse capacity. Maintain optimum statistical requirements.

Financial: Determine detailed pricing within MD’s guidelines. Calculate contribution to turnover by range. Maintain close liaison with accountant. Maintain optimum statistical requirements. Implement all T & N financial reports.

Administrative: Oversee all incoming and outgoing papers. Maintain ECGD cover as necessary. Liaise with Area Managers, Export Sales Manager, Designer and Pattern Book Manager. Oversee supply of materials to Pattern Book Manager and book requirements from him.

It was certainly no sinecure. I was kept busy. Not least, it has to be said, because Ken developed problems of his own: a medical (heart) problem which demanded a by-pass operation; and later, a serious problem with his 25-year marriage which led to a divorce and remarriage. I had a good team: Terry Collins ran the Orders department satisfying customers; Ken Broughton dealt with orders and transport for import and export; and Jack Smith ran the Accounts department. Together we kept the name of Harlequin in the forefront of retailers’ selling efforts.

There is mention in that job description above of “T & N”. Shortly after I joined Ken’s Company, it was taken over first by Storey Bros and then (big fish, smaller fish) by the great Turner and Newall, which proved to be a most interesting exercise. Whereas Storey Brothers were in the wallcoverings business – they produced Ken’s Vinyl designs apart from anything else – T & N were interested in finance and nothing more and requested from me the most exhaustive figure telexes every month that it was possible for a bureaucrat to devise. What was interesting to me about these two parent companies of ours was the poor quality of middle management: the “Peter Principle” seemed to be rife and I took the opportunity to tell them whenever it was appropriate that they could learn a thing or two from the Services about mid-career training.

I suppose the most critical task I took over was the ordering of stock. Before I arrived, Ken had personally been keeping stocks at sensible levels, judging rates of sale of his import collections and ordering in quantities mostly of dozens. By creating the Harlequin Vinyl collection and establishing links in up to 20 foreign countries, stock orders were to rise to thousands rather than dozens, thus enjoying significantly greater quantity discounts. I devised a simple equation to be used in a programmable calculator (the PC was still some years off) which enabled me to forecast demand based on past trend. It was a responsibility which I had to take very seriously indeed. I went hideously wrong once. The vinyls could be categorised under – for instance – plains, stripes, floral, patterned, blown, geometric and so on. It happened that there was one particular geometric which was going great guns all over the place – domestically and abroad. There were advantages in placing orders up to a 2,000 roll run – even more if one went to 4,000. I took a chance on this geometric and ordered 4,000. Immediately after they had arrived in our warehouse, the trend fell off literally to nothing. My embarrassment was acute. Eventually we had to sell the lot off to the HQ of one of the retail chains at less than cost. Fortunately, this was a rare occurrence.

The pricing structure of the product – a roll – was simple: it would cost £x to make; the consumer would pay £4x each for a few rolls – ie sufficient for a room, a “room lot”. We would sell to the retailer at varying figures between the two extremes depending on quantity ordered; we would negotiate the greatest discount where the retailer took his chance and stocked up anticipating sales; the least discount where only a “room lot” was ordered by the retailer. It was a commercial enterprise in which the PC of the future (early 1980s) would have been a godsend.

Ken recovered well from his heart by-pass operation and worked hard to increase the scope of his business – new collections, new products, new domestic and overseas customers: for the latter he travelled extensively. For a few years after my arrival business was brisk. But things always go in cycles. There were clouds on the horizon. We had a very large overdraft (guaranteed by Storeys) which had been brought about by the purchase of the new warehouse; it was costly in interest. The Pound Sterling strengthened and thus went against us for exports. There were signs about 1979/80 of a falling off of export sales. Coincidentally, Storeys had begun negotiations with Ken to buy him out: he ran rings round the Storey people in achieving the optimum deal for himself at a very crucial point in the cycle. The balance sheet showed a £1 million of stock and an overdraft not far removed from that figure. However, with 25 years of building the name of Harlequin in the market, Ken was finally content to agree a handsome figure for himself. In August 1981 Storeys took everything over, we were all made redundant and I ceased to be a Director of the Company. It had been an interesting experience. When I look back on it, I still recall above all else the thrill of a cultural sponsorship: Ken, ever eager to maintain an up-market image, sponsored a concert by the London Symphony Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall in each of the three years 1978, ’79 and ’80. We thus met conductors Bohm, Previn and Tilson Thomas in addition to senior members of the Orchestra. It was appropriate that he had named his collections for years with musical terms – Serenade, Symphony, Rhapsody, Concerto and so on.

Sadly, Ken’s marriage was falling apart in the midst of all this commercial drama. He divorced his first wife Daphne and later married Andree, who had been the wife of a local solicitor. The couple were soon to emigrate to Spain; Daphne and their son Kim were also to emigrate – westwards to California. It was a sign of the times.

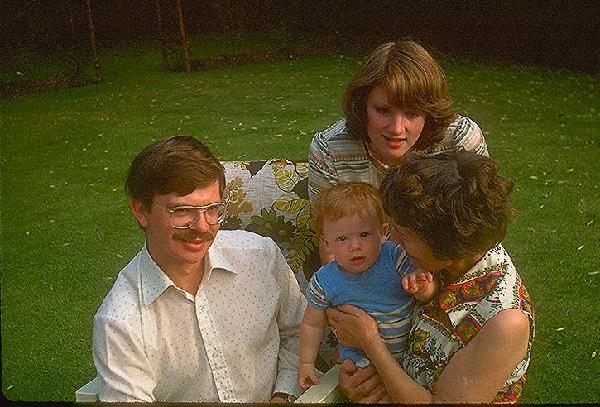

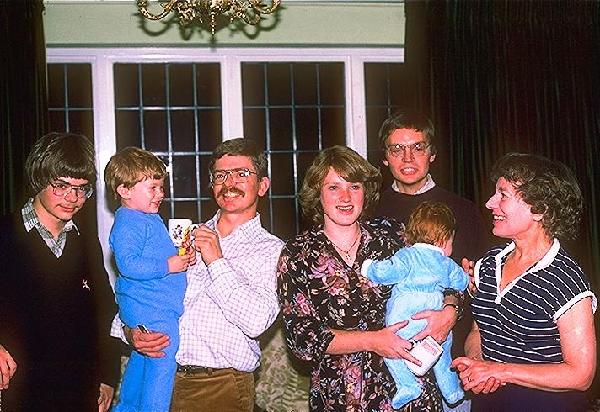

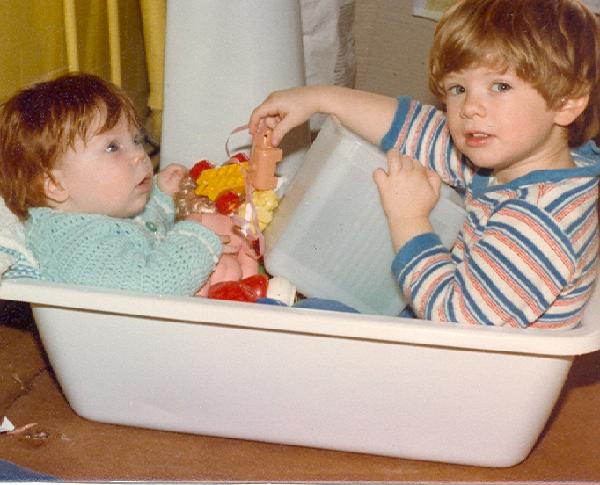

There was much happening in the family during this period. Peter was continuing to make his mark as a Systems Analyst in the mighty IBM and dear daughter-in-law Tricia gave birth to James, our first grandchild, on exactly the same day as Peter’s birthday, 30 years apart, in 1978; and just over a couple of years later, to Catherine, our second, in 1981. At that juncture they moved to a very large Edwardian house in an elegant part of Purley. Peter was active in the local cricket circuit and turned a hobby – tape recording of live events with equipment envied even by the BBC – into a secondary, if minor, source of income; it was through this interest that Pat and I met the charming Japanese piano virtuoso Mitsuko Uchida who has since progressed to be recognised as one of the great concert performers of our day.

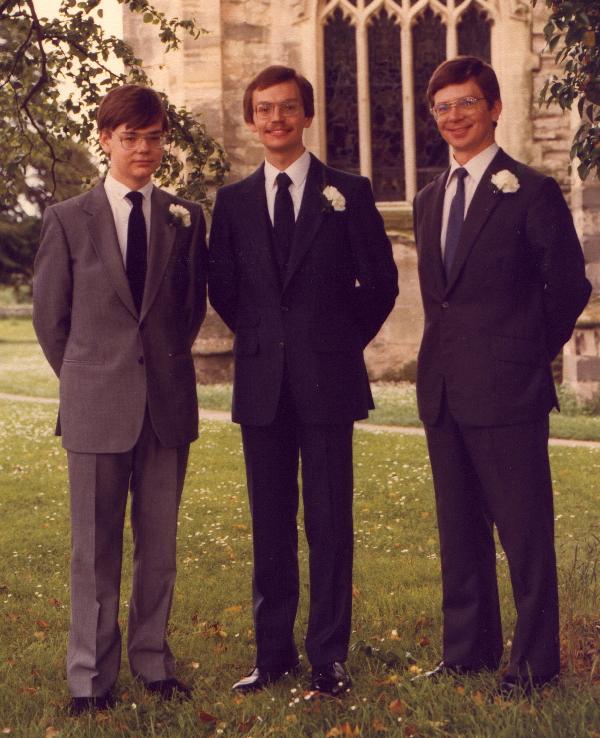

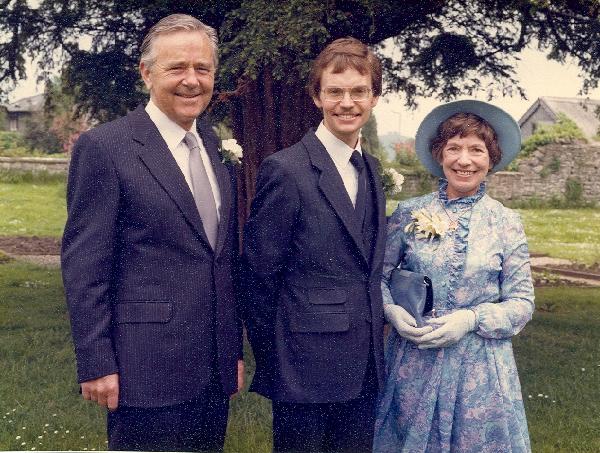

Richard obtained his BA from Churchill College in 1977, won a Bridge Championship in the same year, joined Equity and Law and started a marathon series of examinations for the Institute of Actuaries. Cambridge upgraded him to MA after the customarily decent interval and he later moved to employment in Germany where he met Susan. Richard and Susan were married in 1983 in Keynsham near Bristol. It was a lovely occasion. One of my treasured photographs – Sue will forgive me for saying so – is of our three sons together on the day.

Jonathan, much younger of course, was just 9 years of age when we moved to Stock. The Headmistress of the little local school suggested that it was important to get him into Brentwood School as soon as he reached 10 because it was clear that he needed to be stretched and Brentwood was ideally placed. It was a Public School but he sailed through the scholarship examination and remained there until going up to Cambridge in 1984 just as we were moving from Stock. He was thus the only one of the three sons who lived at home throughout and did not need to board. He has suggested in adulthood that we drove him too hard during this period: I am sure he will realise after we have gone that it was he himself who did the driving: his mother and I were merely encouraging observers of his meteoric progress through the various levels of academic attainment – the Os, the As, the Form Prizes, the General Knowledge competitions, the acting (eg in Stoppard). Of course there were tense moments – there always are – we’ve all been through it.

The beautiful house at 2 High Trees was well suited to welcome guests. They came from the States (Duffy and McKenna of Wright Patterson 1950s) and from Canada (Buchanan of Middleton St George and Boscombe Down; Peden of 214 Squadron). Family get-togethers were frequent and happy occasions, particularly at Christmas. Pat’s parents travelled down on occasions, but their visits became less and less frequent as age weakened them; this was a factor at the back of our minds when we finally moved from Stock in 1984. John Franklin, my step-father, sadly died in 1980 at the age of 82: his final days were most distressing to watch. With no dependents and no will, it fell to my lot to deal with the matters of his modest estate.

Pat, Jonathan and I enjoyed many holidays from Stock – many with the towed caravan and some to a static caravan which we bought in a superb setting at Charmouth in Dorset. We towed to Scotland (in Mediterranean weather!), twice to Wales, to the Peak District, to the Wye Valley, to York and Edinburgh and Warwick; we towed also to Soulac on the French Atlantic coast; and we flew on two occasions to southern Spain to visit Ken and his second wife Andree in their splendid villa at San Pedro de Alcantara, driving on one occasion through Gibraltar and Morocco (swimming in both the Atlantic and the Mediterranean on the same day).

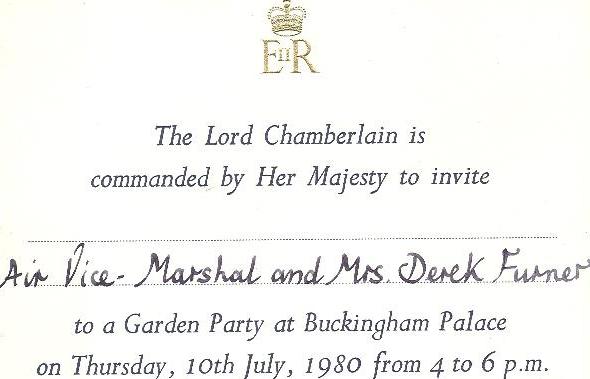

From Stock, it was comparatively easy to travel into London for shows and concerts: we saw Evita (a singularly dramatic evening – see below), Tom Foolery (songs by our old MIT friend Tom Lehrer), My Fair Lady (second time around, with Tony Britton), Amadeus (superb drama), Anyone for Denis (hilarious Maggie take-off), Cats (ALW again), Noises Off (Frayn fun), She Stoops to Conquer (a delight from the past), Song & Dance (yet again ALW), and many Proms in addition to the Harlequin sponsored LSO concerts. We took the opportunity to attend a number of Foyle’s Literary Luncheons at the Dorchester. We were invited to another Garden Party at Buckingham Palace (1980). I volunteered to play the part of a juror in a BBC Radio programme You, the Jury. Coincidentally, I was called for real-life Jury service in a fraud case held in Chelmsford: the evidence of wrong-doing by the controller of an Essex rubbish-dump site was so overwhelming that I had no hesitation in doing a rerun of Henry Fonda in 12 Angry Men, persuading more than half of the rest to change their minds. When the full story of his past misdemeanours came out, those jurors came up and thanked me – which was nice.

Let’s go back to Evita. I thought the whole idea – a modern opera based on the life of Eva Peron – was extremely ambitious; and Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice in my view did a great job with the subject. Particularly memorable was the choregraphy of the Army and the Aristocrats. Elaine Paige was in her first starring role and triumphed. Well, now, this was 1978. A party of six of us – Ken and first wife Daphne, Andree and her solicitor husband Jimmy, and Pat and I – had booked in time to catch the show in the early days of its run; and we had dined together nearby before the show. Tensions started to come into play around the dinner table; they continued to produce a frosty air at the theatre; certain members of the six left their seats, others followed to try to cool passions; the end result was like a scene from the Marx Brothers’ Night at the Opera, A chasing B chasing C, etc, around the aisles and the foyer. Pat and I saw little of the show and returned for a second showing later. Daphne took a taxi home on her own to mid-Essex and locked Ken out. Ken subsequently came to Stock to stay the night with us.

It was a difficult period for all of us. All three – Ken, Daphne, Andree – came at various times to cry on our shoulders. Loyalties were becoming confused. It was a relief when the final deal was made – divorce, remarriage, emigration of all three.

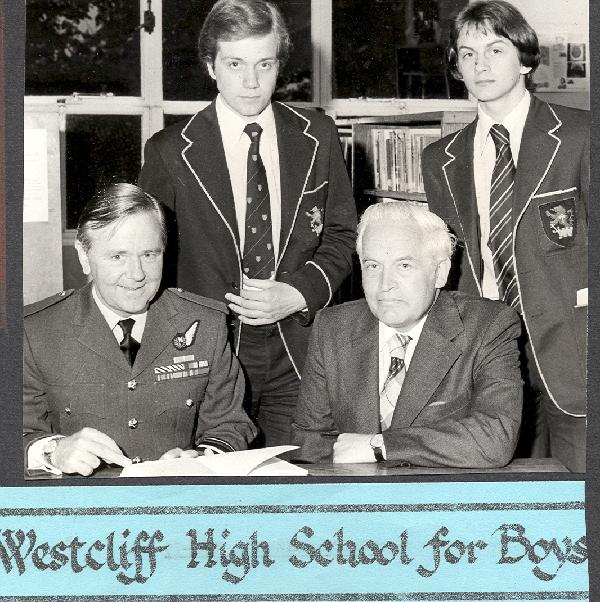

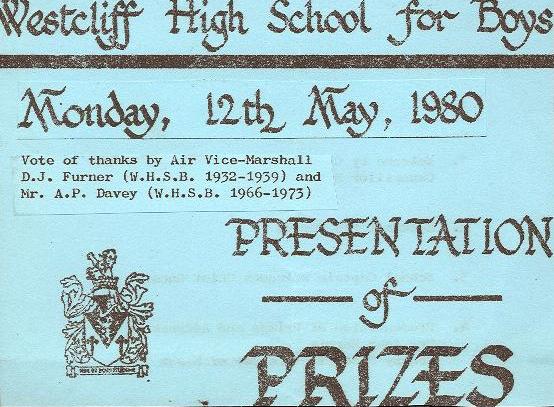

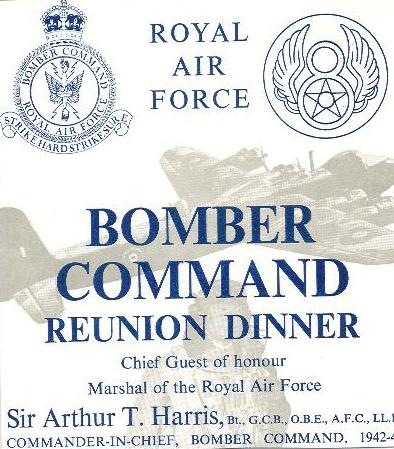

On a happier note, I continued to perform at Alan Clark’s school as Prize-giver in 1977 and 1981. I recall that inflation was roaring away in 1977 and I spoke about it by brandishing several issues of the Beano comic which like everything else was going up fast; I said that if it continued at the same rate until the children got to my age, it would have cost £50 or some such. My old school – Westcliff High – surprised me by inviting me there for a Speech Day, which gave me the opportunity to reminisce about the conditions and the Masters in the 1930s. The local Royal Air Forces Association in Southend-on-Sea asked me to speak at a dinner and it was a delight to meet up again with Sqdn Ldr “Forni” Cater from our CRE days. The charity OXFAM wrote to me to explain that they were putting together a collection of after-dinner stories and I sent them a batch: they published one in Pass the Port and four more in Pass the Port Again. (The books made about £50,000 each for Oxfam.) And, of course, there were reunions – Bomber Command at Grosvenor House with “Butch” Harris attending; 214 Squadron from the war years, and a “Vulcan 25th” year of flight (1956-1981) at my old Station, RAF Scampton. Twice a year there were Air Marshal Luncheons at the RAF Club; and once a year, at Bracknell, briefings by the Air Force Board on how the Service was doing.

Mention of reunions brings me to a somewhat weird message from the past. I have much earlier mentioned (Chap 4, page 22) that there was to be a bizarre sequel to the operation on the night prior to D-Day – that of 5/6 June 1944. The Canadian pilot Murray Peden had written a book, based on letters he had written during the war to his father, called A Thousand Shall Fall. It came to my attention in late 1979: we corresponded and telephoned; he was living in Winnipeg; amongst other information, he gave me the then address of my Squadron Commander and Skipper in the B17s – Wg Cdr Desmond McGlinn. He was living in Santa Barbara in California. I wrote in early 1980 to re-establish contact and to wish him well in retirement. His response astonished me:

Dear Jackie, What a strange voice from the past! I have never forgotten how you wanted to carry on with that mission on the night before D-Day. I couldn’t – I’d had it up to here. And after that encounter with the fighter I had to get back to base. It was good to hear from you………..etc

It was just that first paragraph that astonished me. I had completely forgotten that any discussion of that sort between McGlinn and myself had taken place that night. I had forgotten that our task had not been completed. We were briefed to do so many times back and forth across the channel and we hadn’t done them all. I must have queried him, the Skipper, as to his intentions. I must have asked him why he wasn’t prepared to carry on. I had forgotten all this. But clearly he hadn’t. I felt for him when I read that paragraph: he must have chewed over the implication in my insistence for many years afterwards. The incident meant nothing more to me: it seems that it did – painfully – to him. As I said in Chapter 4, he is no longer with us.

Now, finally, at Stock, let me return to the subject of work. The job with Harlequin lasted just over 5 years, from 1976 to 1981. Despite inflation increases in RAF pension, income was still not sufficient to meet all obligations. Healey as Chancellor of the Exchequer delighted sadistically in higher and higher rates of Income Tax. I had to find further work. I put in an application for an Administrative Directorship at the BBC without the faintest hope of being accepted. It even crossed my mind – but not for long! – to enter as a candidate for the Conservative slot in Southend East: it eventually went to Teddy Taylor. No, the opportunity for something quite light and yet disproportionately rewarding came by chance from Ken’s PA at Harlequin. A very personable young man named Ross Kennedy, he had been set up in the UK by a German company, who did business with Harlequin, to run a UK subsidiary called Eurostudio Ltd; wallcoverings again, based in Harpenden. Ross approached me to help him set up the Company. I was able to do this on a strictly part-time basis, usually one day a week, advising on personnel, administration, payrolls and accounts. It brought in useful additional income.

By 1984, several factors combined to make us think of moving. We had now lived in our 25th home for 8 years; there was between us an indefinable itch to return to Norfolk, Pat’s childhood home and our wartime environment; Jonathan had finished at Brentwood School and was soon going up to Cambridge; the garden was very large and demanding of work; and, despite the elegance and individuality of 2 High Trees, we were becoming increasingly fed up with condensation, noisy Myson central heating blowers and the presence of only one bathroom. Accordingly, Pat and I started investigating bungalows in areas around Norwich. We eventually settled on a very large bungalow in the village of Saxlingham Nethergate, eight miles south of Norwich. It was extremely well-priced for its size (some 2500 square feet) but needed a lot of work. The value of High Trees proved to have risen by 150% since 1976. By moving, we would be closer of course to Pat’s parents who were now both well into their 80s.

So off we went again.