A bunch of us were called up in early 1941. I was 19. We were instructed to report to the recruiting office in Southend’s High Street, where we were allowed to state a preference. I volunteered for the Royal Air Force, for aircrew and, specifically, for navigator. It seemed to me that personality and mathematical inclination made navigator a more sensible choice than pilot: less of the gung-ho, more of the steady as she goes. The powers that be must have agreed: I attended at Air Crew Reception Centre (ACRC) in the hallowed grounds of the MCC at Lords, where the RAF was receiving and despatching tens of thousands of aspiring aircrew, in May 1941—as an Aircraftsman second class (AC2) No 1444259—with navigator training ahead of me. I put on the rough serge uniform for the first time and kept essential belongings (knife, fork, spoon, razor comb and lather brush, we sang) in a kitbag. I was billeted in what would have been in headier days in peacetime a very prestigious and luxurious apartment building facing Regents Park—Viceroy Court.

The bombing of London was still going on sporadically, particularly around the middle of June when Hitler decided to scrap another piece of paper and turn east to invade the vast territories of the USSR. One night during a raid I remember seeing a marvellous Eisenstein film called Alexander Nevsky which drew a remarkable parallel between 1941 and the invasion of the Teutonic Knights 600 years before; the background music of Prokofiev made a lasting impression on me.

The training pipeline was a long one. It was to be nearly two years before I was fully trained to enter a front line Squadron in Bomber Command. It has to be said that the Empire Aircrew Training Scheme, as it was known, was one of the organisational wonders of World War II. Hundreds of thousands of young men from the UK, from the Empire and from European escapers, filtered through a training plan set up on hundreds of airfields in the USA, in Canada, in South Africa and in Rhodesia as well as the UK itself, to feed all the operational Commands of the rapidly expanding Royal Air Force—Bomber, Fighter, Coastal, Transport—with pilots, navigators, signallers, engineers and gunners.

Having performed a bit of smartening-up drill in the back streets of NW8, some of us went from the ACRC to RAF North Luffenham, attached to an operational station, to view the RAF at work and to learn some basic subjects such as Air Force Law and other administrative matters under the tutelage of Education Officers. It was there that Stand by yer beds! became a familiar call as we assembled a neat pile of three “biscuits” and sheets on the bed frame for inspection.

It was there also that I first met an officer who was much later to become well-known to me and a legend in the RAF: he was North Luffenham’s Station Commander and he came round to our little hut one day to encourage us in our studies—it was a very young (29!) Group Captain A (“Gus”) Walker. He had both his arms then. North Luffenham was equipped with Hampdens and I managed to take a local flight in the perspex nose of one of them—my first experience in the air—exhilarating!

Next we were off to Eastbourne for EANS—Elementary Air Navigation School—no flying, lots of navigation theory, living in a guest house. By Spring 1942, since the United States had been hurtled into the war by Pearl Harbour a few months earlier, a US troopship had become an allied ship; and on one of them I found myself bound for New York, travelling very slowly in massive convoy—it took two weeks; enjoying rich American food with lashings of cake and ice cream; swinging wildly on US rating hammocks; and squatting on long lines of “heads” with the effluent flushing in great torrents beneath our twelve-holers. From New York City—no time to stop and look—we were put on a special train all the way up north through New England to Moncton, New Brunswick, in Canada. I can’t remember how long the journey took but it must have gone into a second day. On arrival at midnight, we marched (trudged might be a more accurate word) with our kitbags through a swirling blizzard to a very well heated Canadian barrack block.

The following day another train took us southwestwards along the St Lawrence River through Montreal and Toronto to Hamilton, Ontario, where we disembarked and were driven up an escarpment called Mount Hope. Here on top of the “Mount” was No 33 ANS—Air Navigation School—which was to be our home for the next six months.

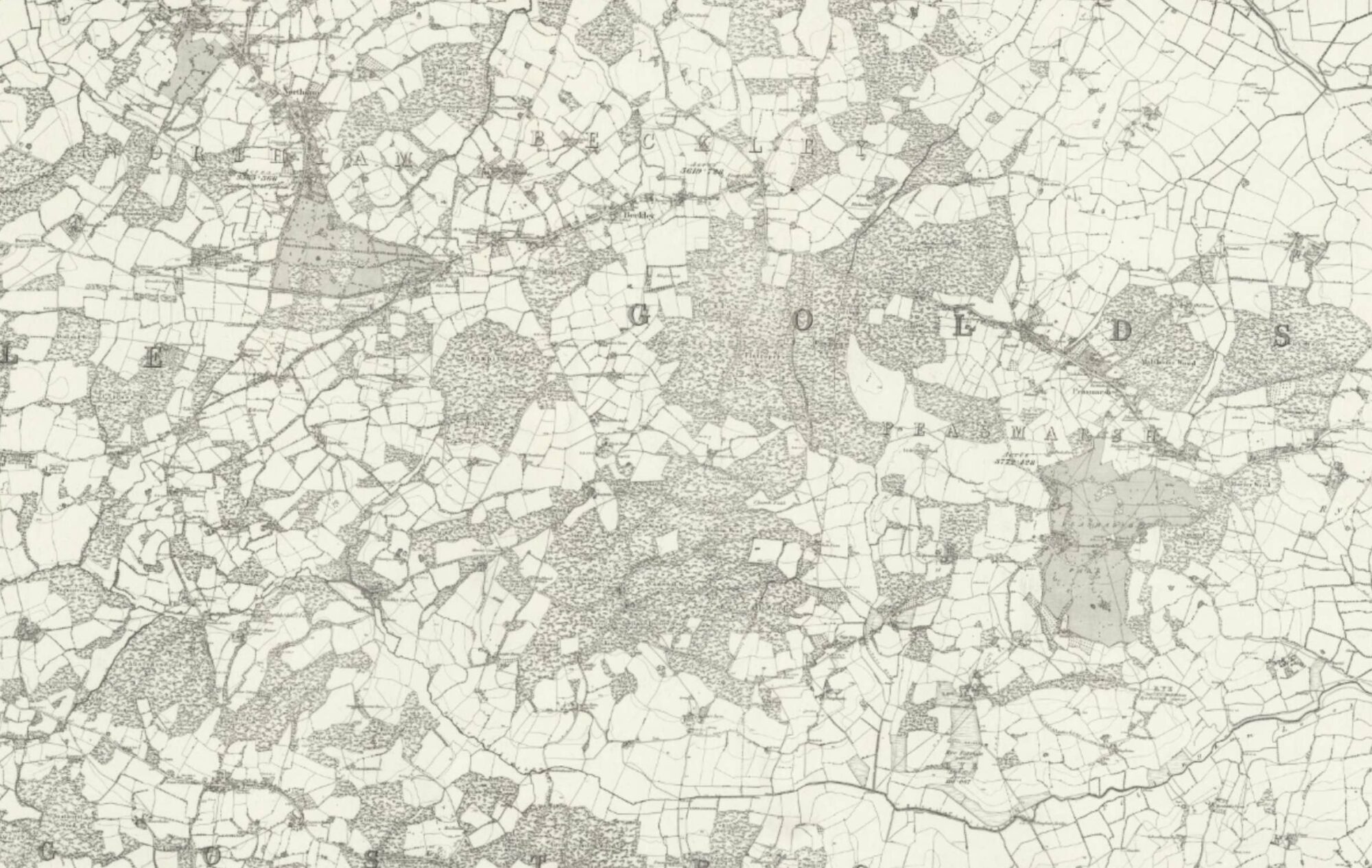

Mount Hope was an exhilarating experience. Of course there were many hours of classroom lectures, on Maps & Charts, Physics, Instruments, Signals, Meteorology, Reconnaissance, Aircraft Recognition as well as the basic Elements of Navigation, but these were complemented by practical work in the air, flying through a Canadian summer; a total of 38 flights in the twin-engined Anson. The flying represented the most significant part of our training so far. It was our first opportunity to put theory into practice. My log book records a gradual assumption of greater responsibility: Map-reading; Wind Velocity by Track and Groundspeed; Groundspeed, Course and ETA (Estimated Time of Arrival); Airplot, Course and ETA; Climbing on Track; Reconnaissance; Drift finding; DR (Dead Reckoning) positions, snap course, recce; Square search exercise; Position lines; Target to be reached 2 hours after setting course; Operational simulation at 10,000 feet, evasive action, certain landfall.

I suppose the most telling phrase in that list is Dead Reckoning (DR). The wealth of navigational equipments today at the end of the 20th century—satellite, inertial, radar, computers—supersedes that phrase and makes it a quaint piece of navigational history. In the early 1940s there were no such equipments—only mapreading if you could see the ground, astro if you could see the stars, and radio beams (if they were not jammed) which would give you a vague bearing.

The essence of air navigation was bound up in the Triangle of Velocities. If there were no wind, air navigation would be extremely simple. Almost always there is wind, and it varies with height. Whatever the aircraft’s instruments say it is doing, the effect of wind is an additive simply because the medium in which the aircraft is flying is itself moving. Thus the famous triangle has three vectors: first, course and airspeed—second, wind direction and speed—and the two add to make the third, resulting track and groundspeed. The angle between course and track would be drift. Wind is critical to one’s knowledge of present position. Even today with fast air transport, the difference between a westerly crossing and an easterly crossing of the Atlantic is most noticeable, mindful that upper winds are usually westerly in our latitudes. So—Dead Reckoning is a calculation of probable position based on knowledge from instruments of compass course and airspeed, together with forecast or calculated wind speed and direction. It is the aim of the navigator to update the DR calculations as often as “fixing” allows, whether from visual observation or from some instrumental means; in Ontario with the Anson, the latter meant radio bearings taken from different stations to form a cross of “position lines”, or, at night particularly, other position lines obtained from sextant observations of stars. ..Or planets, of course: there was a story—possibly apocryphal—that a navigator student was delighted on one occasion that his sextant operation on Mars had been so steady; he discovered later that he had kept his sextant trained on the port (red) wing light.

One can put the microscope on any small part of the calculations. I certainly don’t want to rewrite a manual of air navigation (it was Air Publication 1234 and was a weighty tome) but just as an example, let’s look more closely at that single, simple, parameter “course”. What is the “course”? You read it from a magnetic compass, yes, but compasses have errors in them which you correct as far as possible by “swinging” or (Navy) “boxing”; any residual error is “deviation” which can be graphed against indicated course. Even if there’s zero deviation the magnetic needle is pointing not to true north but to magnetic north. The difference between the two readings is known as “variation” and itself varies according to your position and year. To remember whether the corrections are additive or negative, there was the useful mnemonic CDMVT—Compass plus Deviation equals Magnetic plus Variation equals True—or more memorably, Cadbury’s Dairy Milk Very Tasty. There was a similar progression of calculations from Indicated Airspeed on an analogue indicator to True Airspeed, depending on height and temperature.

The Anson was eminently suitable for basic navigation training and a very reliable aircraft. It lacked the sophistication of later generations. It was the student navigator’s chore to wind up and down the Anson’s undercarriage: it took 146 turns on a large handle for each operation.

On 31st July 1942 I was passed out of Course No 47 at No 33 ANS, as a Pilot Officer in the General Duties Branch (that is, the flying Branch), wearing an “O” for Observer wing and a white band round Sergeant’s stripes on the left arm because Hamilton had no officers’ uniforms. In order to put the result of the Mount Hope course into telegraphese, I remember sending a cable home reading, amongst other things: Top of Course. I had meant the three words to be factual, but at home, the second and third words, all appearing in upper case, were misconstrued and thus taken to confirm my usual conceit.

My officer number was 127259 which produced the same last 3 digits as my airman number—a nice coincidence.

Three of us set out on a couple of weeks leave, in our serge uniforms and white armbands, to hitch-hike to Niagara, Buffalo, Schenectady and New York City. It was so easy. The Americans had not long been in the war and we were unusual people. The hospitality of everyone we met was overwhelming. I remember we met up with a bunch of young girls in Buffalo: they took us back to one of their homes for a transatlantic party. One of the fathers was a senior Buffalo policeman and another worked in the Fire Department. On leaving Buffalo to head further east into New York State, the Fire Department drove us to the City limits and the accompanying Police car stopped the first suitable vehicle going to Schenectady. Service, indeed. Schenectady, the home of the General Electric Company, was remarkable (then) for orange street lamps—never seen the like before. In New York, after half a dozen more generous and inquisitive responders to our thumbs, we put up at the YMCA, and saw everything and did everything we could in the time. Particularly memorable for its welcome and camaraderie was Jack Dempsey’s Bar on Broadway: New Yorkers queued up to buy us drinks. The whole trip was magic. But it had to come to an end and we hitched back up to Canada. Packing kit bags, we were soon on a train which took us the reverse way back to New Brunswick since Moncton had the honour of being the focal point both into and out of the Canadian Training organisation.

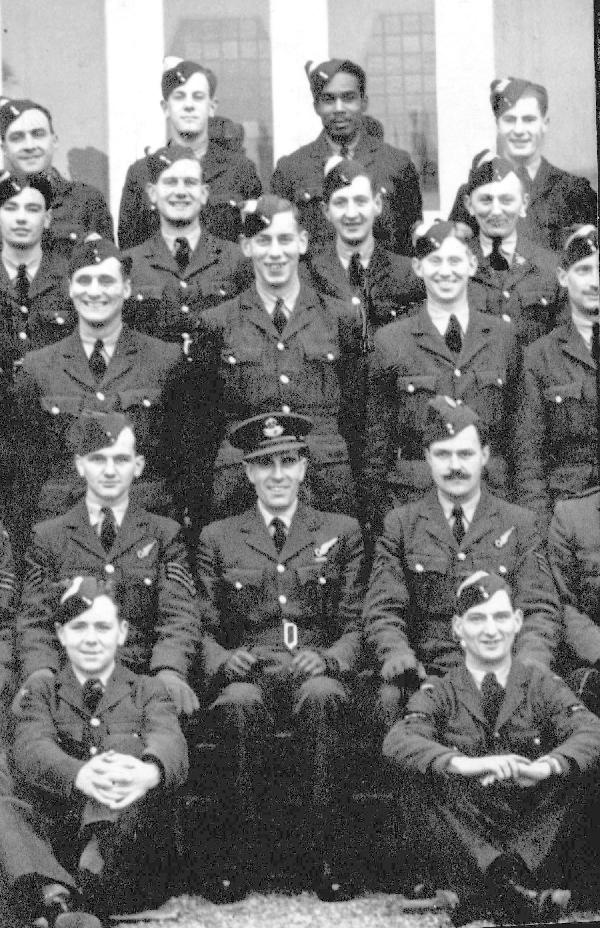

After equipping ourselves properly as Pilot Officers in Eatons Department store in Moncton, we returned to the UK in style by a one-class ship from Halifax to Liverpool and eventually made our way to Bournemouth for another short period of waiting—waiting for the next stage in the pipeline along with raw aircrew from all parts of the world. It was here that the decision was made as to disposal—which Command, Bomber, Coastal, etc. For me—and for most trainees at that time—it was Bomber and I was told to report to No 11 OTU—Operational Training Unit—at RAF Westcott. We grouped ourselves into crews for training on Wellingtons: my skipper was a tall laconic New Zealander named John Verrall and the rest of the crew hailed from Scotland, Wales, Yorkshire and New Zealand: Sergeants McDonald, Beswarick, Boyd, Shankland and Wilkes.

Up to this point, relationships with one’s colleagues were transient: through London NW8, Luffenham, Eastbourne, Moncton, Hamilton, Moncton again, then Bournemouth, I had made many friends at each place, but we never saw one another again. Now, for the first time, we were a crew of seven who were to be together for a tour of Bomber operations, who were to rely on each other for the safe completion of that tour and who were thus dependent on each other for our lives.

We are in late 1942. The news was good in North Africa, but nowhere else. Severe losses of shipping tonnage were being reported every month as the U-Boats found their targets on the Atlantic; the Russians were withdrawing hundreds of miles to team up with General Winter; the vast area of the Far East had been overrun; and the USAAF had not yet got into its stride in the UK. The only punishment to be inflicted on Germany itself was from night raids by Bomber Command which were gradually becoming more effective under the leadership of Air Marshal “Butch” Harris.

Westcott was one of the Air Marshal’s 100-plus airfields. Our flying at Westcott—20 Wellington sorties—was vitally important for two reasons: firstly, to accustom ourselves to Bomber Command procedures in all their aspects; and secondly, after the unnaturally good weather conditions and lighted towns in Canada to get used to the much worse weather conditions and the black-out in the UK and across Europe. The good news navigationally was the addition to the navigational setup of “Gee”—an electronic aid based on master and slave stations on the ground, giving rise to measurements of time differences and thus a lattice of hyberbolic lines, two of which would give a “fix”. The navigator would align blips on a CRT and read off coordinates which would relate to the lines on a pre-printed chart. Near the ground stations, the lines would cross at a marked angle and accuracy was good; at increasing distances, for instance into Germany, the lines crossed at a small angle and accuracy fell off. Euphoria over this new black box was to be shortlived: we discovered later that, along with any electronic device, it was jammable.

By the time we were crewed I had been promoted to Fg Off (nothing special—time promotion). John Verrall was (initially) a Sergeant and was commissioned during his time later on the Squadron. Sergeant or no, he was the skipper. Army visitors—and we had them from time to time—could never understand this. A Lieutenant calling a Sergeant “Skipper”! Unheard of; definitely infra dig. In the RAF, in the air, it worked. We all had our separate jobs in the air, our separate responsibilities, and we worked as a team—pilot (skipper), navigator, bombaimer, engineer, signaller and two gunners, midupper and tail. Woe betide those crews who couldn’t work together with one another. Nothing worse than an argument in the air, say, between the Pilot and the Nav.: it got the rest of the crew unsettled and nervous. My relationship with John Verrall was excellent: he was a very good pilot, steady, reliable, cautious and yet decisive. I did my best to match him in navigational expertise.

The next stage—no, we haven’t reached our operational Squadron yet!—was for our crew to be posted to No 1651 HCU—Heavy Conversion Unit—at Waterbeach, because of the need for all of us to become accustomed to the Stirling itself, the first of the four-engined bombers. Nine sorties were sufficient to declare us ready at last for the front line. Whilst at Waterbeach we spotted a Stirling one day that looked different. It was pregnant with a huge curved bulge under the forward part of the fuselage. Ah, somebody said, you can see the ground at night with that thing. We were mystified. In a few months we would know more.

A word about the Stirling: we called it the Queen of the Skies. On the ground, with tail wheel and not nose wheel, the cockpit was an awesome couple of storeys high. It was a beauty to fly at low level and it looked magnificent. But its height performance was abysmal. It was a struggle to reach 14,000 feet. In consequence we had the uncomfortable feeling that the Halifaxes and the Lancasters—up at 20,000 feet—were always dropping their loads through us—not nice. The problem with the Stirling was the wingspan. Had it been designed a few feet wider then the height performance would have improved. But hangar width demanded that wingspan should be less than 100 feet. And so that is how Short Brothers built them.

We were ready for war.