In this Chapter and the next I make use of letters which I wrote to Patricia during the two and a half years separation. I have taken excerpts, unedited, which carry the story along. They represent probably less than 20% of the total correspondence.

At the beginning of 1945, despite the rather startling “Ardennes” offensive staged by the German Army, it was at last, after more than five years, becoming increasingly clear that the War against Germany could be won with the combined strengths of the three “U”s—the UK, the US and the USSR. It also began to look as if the world had a reasonable chance to return to peace that year. But first—there was Japan. US Forces were slowly but surely driving the Japanese back across the Pacific, island by island; the British 14th Army was slowly but surely getting the upper hand of jungle warfare in Burma. It was all painfully slow and could still cost many lives.

I was posted from RAF Oulton to RAF Leconfield further North to team up with a fresh crew who were to be trained on Halifaxes of No 96 Squadron to take on the role of Transport. I was grouped with a pilot, Flt Lt Hazelhurst; co-pilot Fg Off Southwell; and signaller Flt Sgt Mellor. This size of crew was adequate to our future task: although we were training in the UK on Halifaxes, in the Far East theatre we would be flying Dakotas, or DC3s as the Americans called them. We started with ground school sessions and completed the course with a couple of flights oriented to Transport Command procedures.

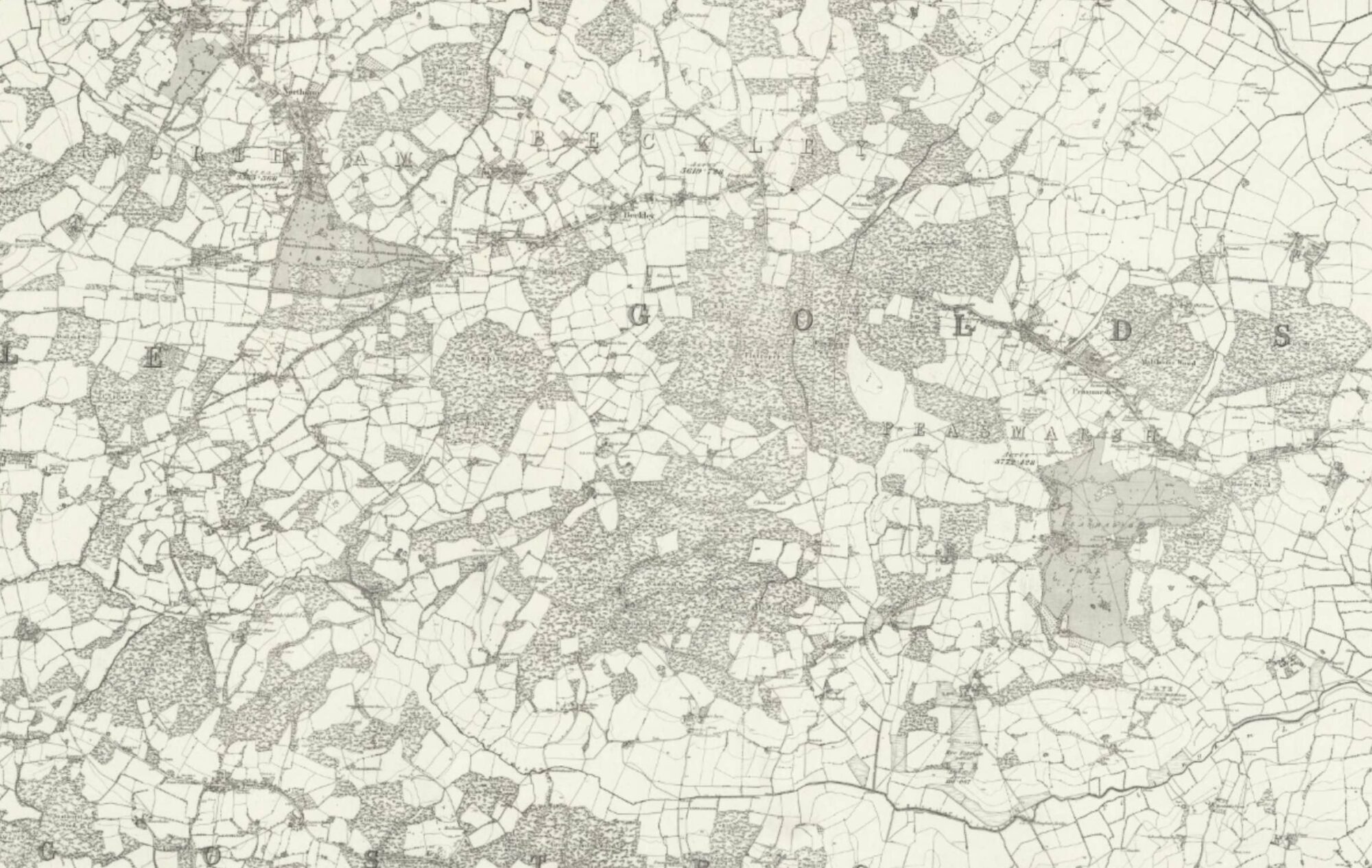

I must have been accident prone around this time of my life. Something happened to me which held us all up for a month or so. I had an old Ford 8 (cost £25); we had been to Beverley one evening for a few drinks at our favourite pub. At about 10 pm I drove us all back to the base. Now you have to realise that there were no lights on any roads during the war. Everything was blacked out. Headlights of all cars had to be fitted with a screen of horizontal shutters to ensure that an enemy aircraft could not see the beam from above. The road back from Beverley was straight as an arrow, but had some nasty dips in it: one minute you’d be aiming several degrees down, and all of a sudden you’d switchback to several degrees up. At such a point that night, I was horrified to see ahead of me, immediately after a dip, a large truck, stationary with no rear lights burning. I hit it.

I woke up on an operating table which I later found out was in Beverley Hospital. They were just about to close up a rather nasty gash on my upper forehead which apparently had appeared when I went through the windscreen. I had lost a fair amount of blood and had been raving in some sort of unconscious delirium. It was lucky for me that the other chaps in the car had suffered only a few scratches and bruises and were able to stagger to a nearby cottage and call for an ambulance. The truck had been an Army vehicle: it had broken down and there had been no chance of illuminating it whilst the driver went off for assistance. So there I was with a crowd of people round this operating table; and, heaven help me and spare my blushes, I chose that very moment to need a powerful bowel movement. Good grief: but I suppose nothing fazes these dedicated nurses and doctors.

Anyway, I was in the Hospital for quite a time; the crew popped in every now and again and somebody managed to sell the car as scrap for a fiver. I was released from the Hospital just in time to be told that we were all to join a ship from Liverpool to Cairo. A ship? Why a ship in those days of massed armadas of aircraft available, I shall never know.

“19.04.45.96 Sqdn RAF MEF. A hurried note to let you know I’ve arrived out here. I’ve been travelling by sea for some weeks, a delightful cruise on the Winchester Castle, very much pinker than when I left England. I’m excited about the job ahead and intrigued about our next move but I can’t help feeling frustrated that we should be out here in this Godforsaken country just as the whole show in Europe is about to finish and the victory celebrations will be getting under way. I must say I’ve rarely seen such a feudal system as they have here. The sharp division between the rich in their beautiful white villas and the poor in their mud hovels is striking. Still—the big city is entertaining: all the shops you could wish for, at a price; all the food you want; cabarets, cinemas and Donald Wolfit in a Shakespearean season. These do help to relieve the tedium of heat, sand, flies, tents …”

On arrival in Egypt in the early part of April we were moved around a bit but finally quartered at an RAF base called Bilbeis, a collection of tents way out in the desert. From Egypt we were destined to continue by air—and I should think so too. But for me, believe it or not, there was a significant delay for medical reasons. I spent the whole of the second night in the latrine tent and was diagnosed the next morning with typhoid. Some cook’s dirty fingers, no doubt. I languished for the following four weeks in Cairo Hospital whilst my colleagues were on their way to India. The daily performance was rather like that in Alan Bennett’s splendid play The Madness of King George wherein the royal physician meticulously examines the royal stools. But I survived. By the time I left that Hospital, it was warm and I felt very uncomfortable in my blue serge. Everybody else had changed into summer khaki.

“05.05.45. Most of the boys have gone already, leaving behind a small rearguard. It will mean one merry hell of a chase to make sure all kit is in one spot—which it isn’t at the moment—and to buy tropical kit which I still haven’t got. Accustomed as I am to move from one station to another in England with dignity, comfort and assurance that I have everything, you can imagine that the Furner mind is in a bit of a whirl.”

So on the 11th May 1945 I started flying east as a passenger: first to Shaibah, then to Jiwani, and Karachi and finally arriving at Bilaspur in the middle of nowhere in Central Provinces, India, on 14th May. The smart and knowledgeable among you will realise from those dates that I spent V-E Day, the day I had in my small way helped to bring about and the day when London and the rest of the British population went wild, in Cairo Hospital.

“12.05.45.96 Sqdn RAF SEAAF. My first impression of the subcontinent of India you might think rather strange. It struck me that I hadn’t seen a greater concentration of pornographic literature in any other country. Tales of erotomaniacs, nymphomaniacs and sexual perverts are too common. Then in the more arty line you get Nana by Zola, Daudet’s Sappho, Balzac’s Droll Stories, Fanny Hill and stacks of D H Lawrence.”

My crew, skippered by Roy Hazlehurst, welcomed me with open arms at Bilaspur, I’m glad to say. But within 48 hours of arrival we were fully packed and off in our Dakota to Dum Dum (Calcutta) and on to Comilla in Bengal. For the rest of the month of May it was GO all the time—mostly supplying the Army in Burma who were getting on top of the military situation there and harrying the Japs. We were dropping things, we were delivering things, we were stopping off at new places with exotic names—Hathazari, Rangoon, Akyab, Cox’s Bazaar—and amongst other supplies, for instance, delivering the Meccano type pieces of PSP (Pierced Steel Planking) which assemble as a makeshift runway. There was hardly a day in May when Hazlehurst and his crew were not operating.

“21.05.45. Central India was hell. A temperature guage in an aircraft shot out of the roof at 158. The order of the day was 10 pints of liquid and bags of salt to keep pace with the sweat. An average day started off at 6 o’clock—spot of work till noon—then sit down and just sweat and pray for Mr Bromfield’s Rains to Come. In the evening, much more liquid, mainly lemonade, and a little deep thinking just to convince yourself you’re still sane. The last bit of business in the daily curriculum was the meticulous inspection of the inside of the mosquito net. If one of the damned things is already there, the object of the net is defeated. Once inside, sleep on top of the sheets and sweat out the last of the ten pints. So ends the perfect day. But enough—on with the news. Two days ago I happened to be in Rangoon—bombed, blasted, streets discoloured with a mixture of blood and betel juice, and a most unhappy stench of decaying flesh. In short, a shambles. Strangest thing was the Japanese paper money littering the streets. Absolutely valueless, but nevertheless a good souvenir—as was also a Jap signboard in the shape of an arrow that we carted back to our plane (which now and again becomes home and hearth.) Whether the sign says Gentlemen or Defense de Fumer we haven’t yet discovered.”

Let me just say a word about navigation technique in this theatre. It was totally different from the Bomber Command experience. It was all by day, none by night. The flying was mostly at low level. The Dakota was twin-engined. It was extremely reliable. [There are DC3s still flying at the turn of the Century in various parts of the world.] If the weather was good, navigation was all by map-reading. If it wasn’t—and later in the year we were to see the difference—flying was all in cloud and dead reckoning came into its own, supported only by radio bearings; woe betide the navigator (and his trusting crew) who had screwed up his DR and came down through the cloud over a mountain rather than a valley or the coast. There were many occasions when I was required to advise skipper Roy, who was flying solely on instruments in cloud, that it was OK for him to descend through the cloud to get under it and see the terrain.

“26.05.45. I can’t remember ever having seen such storms as you get out here. I watched one last night for a solid hour, awe-inspired by the terrific power of the elements. Lightning lighting up the whole place like day about every two seconds. And the rain! Lakes and ruddy inland seas appear overnight. With the perpetual moisture in the air it’s the devil’s own job to keep things dry: clothes are always sticky; cigarettes are always limp; and matches—good heavens, the matches they make!—never damned well strike.”

On the last day of May we were instructed to fly back from Comilla to our starting point in Bilaspur. Once there, we embarked on a very strange mix of activities. One of those activities was to move various types of supplies—for instance, fruits and vegetables—around India, calling in at Delhi, Agra, Calcutta, Raipur and others; this sort of flying gave me an opportunity, under skipper Roy’s watchful eye, to fly the Dakota myself.

“03.06.45. After a brief operational period, yes, I’m back in mighty India, right slap in the middle. But not the India you imagine—not the glamour and the mystery, the pagodas, the temples and the elephants. They exist somewhere far from us, but not here. Here the picture is flat, hot, dry, sandy, dusty, bug-ridden, flea-ridden and bloody. The odd erk dies now and again frothing at the mouth with a mere 110 degrees. The only living things besides a handful of mad airmen are a bunch of weary Indians and the odd worn-out cow. Perhaps it’ll look a little more inspiring when the Rains come, but until then we sit, suffer and sweat.”

“12.06.45. There is little doing here and less being said. My main thought all day and every day is health—and it’s the same for everybody else. One has to be careful not to eat too much; not to drink too little; to take salt; not to eat any cut fruit; not to drink strange water; to take mepacrine (anti-malaria) tablets; to use powders to stop sweating. And so it goes on. Despite three showers a day and change of clothing twice a day, many of us have the unpleasant rash called prickly heat. Apparently no chance of its going until the rains come.”

“16.06.45. The Rains have come! The rains have come at last to this desolate and parched land, and we breathe again. Yesterday the dust eddied in little whirls over a baked and crusted ground, water was at its lowest ebb and the peasants’ rice stock was running low. Today heavy billowing cumulus clouds rear up from nothing, violent winds blow up the last duststorm, the ominous rumble of thunder is heard in the distance, and the rains are falling—all this in a matter of hours. Soon the dust will be laid, the fields muddy and ready to take the rice seed, and what greenery is left will bloom again. The air will be cool and smell sweet. … They have distributed voting cards here sufficient for only one quarter of the men! [General election, 1945.]”

“21.07.45. India’s got me again. I’m in hospital now with what is officially put down in the book as NYDF—not yet diagnosed fever. Diagnosed or not, for the first couple of days it was unpleasant. A temperature of 103.5 can be a bind to say the least. Produces a certain feeling of malaise. So once more this infernal climate has beaten me. I don’t think I shall ever be able to claim that I’ve beaten it.”

“22.07.45. Third day in hospital. Bored to tears—nothing readable except a well thumbed Thorne Smith and a week old Hindusthan Herald. I was going to tell you about the Taj Mahal, wasn’t I? It’s certainly all it’s cracked up to be—a really magnificent effort. A chap by the name of Shahjahan built it as a tomb for his wife Mumtaz Mahal. It took 20,000 men 17 years to build and cost £2,000,000. The whole thing is made of different coloured marbles and was planned by architects of many countries. The story goes that the foreign architects were thrown from one of the pinnacles when the task was completed so that they should build nothing more beautiful. To enter, of course, all visitors must take off their shoes—and on this particular day, socks also—it was raining hard. What struck me most about the place was the exact symmetry of it. The old boy must have been well up on his Euclid.”

“30.07.45. What an extraordinary election result! 380 to 190. The voters have realised that if we have Churchill we have to have his whole Party, so they say—‘We won’t have Churchill’. Whether the Labour Party carry out their promises to the full extreme is another matter, but at least they had a definite policy. Calcutta was a very crowded and very smelly city. A sprawling mass of dirty crowded hovels and a small area of business establishments. One hotel of any size, again very crowded. A few cinemas, fully booked every day early in the morning.The only other entertainment, a cabaret charging exorbitant prices for admission and a meal (10/—for a steak course) and putting on for one’s entertainment a poor collection of depressing artistes—one of whom was an Anglo-Indian woman dancing to Liszt’s 2nd Hungarian Rhapsody.”

“10.08.45. Today I took a day off and paid a visit to the local town (Bilaspur)– my second only. I don’t think I’ve ever described it to you, so here goes. First of all, one bumps and crashes in a truck for ten miles over one of the world’s worst roads. Exhausted on arrival, the obvious thing is to have a cup of char. Recuperated, next a look around. It’s a town of 100,000 people. It has its poor quarters, dirty and squalid, hovels in tightly packed streets, teeming with human and animal life; and its ‘residential’ quarter—a few whites and the more prosperous Indians, pleasant streets with plenty of flowers and trees and lots of space. The two meet at the main focal point of the place—the railway station. Here the scene is all too typical of India. Fat prosperous Indians of the higher castes slinging orders around left and right with a perpetual leer on their faces, beggars squatting on the dirt and dust, crying the familiar baksheesh and spitting from a lean consumptive frame every so often; ragged little boys running around, vying with each other to carry an Englishman’s bags, others sitting and eating a mango with two flies to each bite; the women, always the fittest of the family, doing all the hard work, carrying baskets on their heads and walking with a grace and bearing to be envied by any Hollywood mannequin. Then there’s us—the temporary ones—sweating, profusely cursing the flies, the dogs, the goats, the cows—India!”

The other activity—much more significant as we later found—was to co-operate with an Army unit based fifteen minutes flying time away at a place called Kargi Road. We were training to carry paratroops and to pull gliders carrying other troops. We did quite a bit of this: we even pulled gliders in formation with other Daks on the Squadron. Once I went into the glider to see how it felt for the Army chaps: the effect of keeping a constant eye on the cable tailing back from the Dakota was mesmorising. So—what was all this about? Couldn’t tell Patricia. Well, we didn’t know at the time, but it became common knowledge much later that we had been training for Operation ZIPPER—the invasion of Malaya. This would have involved long distances for our Dakotas, and it was planned that, having disgorged our paratroops and released our gliders, we in the Dakotas would be expected to land somehow on the beaches of the east coast of Malaya. A one-way mission. D-Day would have been in late August. Interesting, to say the least.

Fortunately for us, it was not to be. American and British scientists had been working towards the creation of a fission-bomb, the “Atomic Bomb”, and there had already been successful tests in the Nevada desert. President Truman took the fateful decision to drop one bomb over Hiroshima on 6th August 1945; a second on Nagasaki on 10th August; the effects were awesome; the Japanese surrendered on 14th August. Thus a new age had begun—the nuclear age; and two nuclear weapons, the only two to be dropped in anger in the whole of the 20th Century, brought the most fearful and destructive war the world had ever seen to an end. It was fortunate indeed for the world that the Germans hadn’t got there first.

“12.08.45. Such momentous news! All in one week comes the atomic bomb (!), the Russian declaration of war on Japan and then yesterday Japan’s peace offer. At the moment we’re all waiting for the announcement of VJ Day. I notice already a marked tendency to imbibe more alcohol, and not merely as a spectator. But don’t imagine darling that all this will mean my speedy return. Far from it. I expect we, as Transport, will have a hell of a lot to do. I should be very surprised if I got back before Christmas. I must tell you rather an amusing story. It’s true. An aircrew type out here in India went on leave 7 months ago for 28 days. He met a pal ferrying to England, hopped aboard, went home, returned by the same aircraft and was back at his camp well within the 28-day period. Now a week ago, his CO called him in and said ‘Bad news I’m afraid. Wife’s going to have a baby. I’ll arrange immediate repatriation for you’. Well! C’est une idee, as they say.”

“15.08.45. Today is VJ Day. As you will gather—as you read further into this letter—I’m fairly tight. ‘Fairly’ is a silly word. It’s used to indicate that I’m not particularly sober and yet I’m not in an alcoholic stupor. This horrible devastating world war is finished and maybe soon I shall be with you again.”

“03.09.45. Have you thought what today is? September 3rd—6 years to the day since old gaffer Chamberlain said how sorry he was, folks, but I’m afraid you’ve got to go to war. I had just left school, smug, precocious, know-all, having polished off the London University Inter BA. If I could conjure up now but one tenth of my academic knowledge then, I’d be happy. But it’s gone—a thing of the dim distance. Six years, and I’ve grown up, we’ve all grown up … Six years, and 30, 40, 50 million people have lost their lives or become homeless..Six years, and Europe is impoverished.. Six years, and I’m 6,000 miles away.”

And thus—of course—Operation ZIPPER was cancelled.

And thus—euphoria at Bilaspur, as in most places around the world. But, after the rejoicing, what next? What were we going to do?

Well, for a start, there was the monsoon to cope with. There are charts of India showing lines of approach of the Southwest monsoon: Central Provinces by mid-June, Delhi by end-June, Karachi (maybe) by August. At Bilaspur we were now well into it. The period before its arrival had been unbearable: one of our airman died just because of the heat—his body temperature went up to the ambient temperature. But once the monsoon had arrived, thunderstorms, heavy and persistent rain, grass appeared again, the emaciated cows started to fill out; even the occasional cyclone brewing over the Bay of Bengal would spread strong winds, continuous rain and dark low scudding clouds over Central Provinces.

The time for rejoicing was short. Within a few days after V-J Day, we were off to New Delhi, and Izatnagar to pick up fruit for Bilaspur.. Then to Hakimpet with a stretcher case, thence to Nagpur and Agra, where, according to my logbook, we picked up a piano and 75 chairs to take back to Bilaspur. That last was on 2nd September. Within another 36 hours we had to be fully packed ready for a posting to the southern end of Burma.

*

So, on 4th September Roy Hazlehurst and his crew flew their trusty Dakota KN422 from Bilaspur to Chittagong, and thence to Hmawbi, pronounced as in Morbid. Hmawbi was a strip of PSP and some tents, some 30 miles north of Burma’s capital city and major port, Rangoon. It was hot and wet—the monsoon was still with us. We’d hardly unpacked and got settled before we were ordered to begin a two-way operation eastwards to Bangkok and Saigon. To those cities we would carry food and fuel, sometimes Army personnel. From those cities we would return with Prisoners of War—British, Australian and Dutch—in order that they could be embarked on ships from Rangoon. Many of the POWs were in an emaciated state, particularly those who had been engaged on the infamous railway from Siam to Burma. There was one British Army Warrant Officer whom I especially remember: thin and gaunt, but still erect and proud, his only concern on reaching home as to whether his daughter had “run off with a Yank”.

This period was an extremely busy one. My log book shows 67 flights between 6th September and 27th November. The cloud conditions were often exasperating. Cumulus would build over the mountains between Rangoon and Bangkok from early morning on and it seemed to us that it was always a race between our rate of climb (which wasn’t impressive) and the build-up of the clouds. The satisfaction we obtained from what we were doing made up for any irritations: we knew we were helping others in both directions—it gave us a good feeling.

“12.09.45. I’ve had 24 hours in Bangkok. Easily the finest city I’ve seen in the East. Modern, clean, lots to buy and to see, and lots of entertainment. Beautiful architecture (some of the loveliest I’ve ever seen), clean streets, fine hotels, night clubs and stacks of well-stocked shops. Many of them specialise in Siamese (black) silverware. I bought a cigarette case, and a compact for you, both of perfect workmanship. The Thai people I found the cleanest, the most intelligent and the most pleasant of all the Easterners I’ve seen so far. We’ve been driven around in flashy modern cars by Jap drivers! “

“16.09.45. I met a new fruit in Siam—delicious; it’s called a pomelo. It’s a huge citrus fruit about 8 times the volume of a large orange. And the bananas are the best I’ve ever tasted. To demonstrate how different these people are from Indians, I went to buy some bananas in a market. The first stall-keeper said his weren’t quite ripe yet and I’d be advised to go to the stall across the way!”

(He was probably his brother!) We met with remarkable hospitality on the part of the Siamese. They had played host to the Japanese for so long; now they switched their allegiance to us, benign invaders. There was one period of a few days when our Dakota went unserviceable at Don Muang airport, Bangkok. We had to wait for spares. The Siamese government put us all up at one of their best hotels and paid for all our food and drink. On some occasions we were invited out by affluent Siamese citizens and given generous hospitality.

“Still on the subject of food, you might like to hear about a Chinese meal we had in town—10 courses!: Shark fins—mustard sauce; Spring Onions and jam; Kidney and shrimp noodles; Chicken something or other; Dove and crab—vinegar sauce; Chicken and ham—lemon sauce; Fish; Fried rice and salad; Soup with a charcoal burner in the middle of the bowl; Swallows nest and lotus seeds; Drinks: Rice whisky, rice beer, Chinese red wine. General Principles: You may smoke throughout the meal; you eat melon seeds throughout the meal; you may lie down half way through if tired, then return to the fray; wet towels supplied every five minutes for face and hands; and, of course, use chopsticks. I’ve just come back from another trip to Bangkok. Had quite a few beers with the Daily Herald war correspondent. Discussed the “petite guerre” in Saigon, much callous fun being had by all.”

“05.10.45. The main topic of conversation on the camp at the moment is of course demobbing. The news has certainly been a bit disheartening as regards the RAF—apparently 27 and 28 Groups won’t be out and about until June. At that rate of release I should reckon that it’ll be Christmas 1947 before I don a sports jacket and slacks. But it’s funny: the very same people who a few months back were praising the Labour Party to the skies with their ignorant platitudes, now turn smartly round and kick ’em in the teeth over the demobbing. They’ve forgotten the aftermath of the last war when unemployment figures rose to meteoric heights. I’m more inclined to take a broad view of the whole thing and realise that it’s probably all for the best.”

It was about this time that the handing out of campaign medals began. One had to fill up forms to justify the ones you were entitled to and presumably they were dealt with by armies of civil servants back at the Air Ministry. I already wore the DFC and the 1939-43 star (now extended to ’45); and was later authorised to add the following: the Aircrew Europe Star with France & Germany clasp; the Burma Star; the War Medal; and the General Service Medal annotated SE Asia 1945-6; my additional bid for the Defence Medal, which was given to all including cooks and bottle-washers, was strangely disallowed.

23.10.45. At last I’ve had a good look at Saigon. I stayed there overnight a few days ago. We arrived about midday and bundled off into town straightaway. It really is a lovely place, even more modern and well set out than Bangkok. Wide streets, hundreds of well-built villas, modern department stores and shops (mostly closed unfortunately). The evening followed up, naturally enough, with a few rumpunches at ‘Chez Jean’ and so back to the rather doubtful comfort of a palliasse on a bamboo bed. But all is not joy and gaiety in Saigon. Far from it. The people there have very little to eat—we couldn’t find a meal anywhere—and the Annamites are still a constant threat to everybody’s well-being, including our own. During the night we heard quite a bit of heavy gunfire around the place. Earlier in the evening, the French Army—or part of it—had straggled up the main street (Rue Catinat) from the quayside, loudly applauded by the local French, while the RAF was busy buying champagne at 3 bob a bottle. (‘Notre guerre—c’est fini. La votre—hah!’)

“30.10.45. 5 days silence I’m afraid—more flying on odd trips, mainly Akyab. Catastrophic confusion in Met circles: the Rains are back again! They shrug their shoulders, put out their hands, a bewildered expression on their scientific faces and murmur ‘It should have stopped.’ You asked about currencies. 1 Tical is about 4d; 1 Piastre about 3d; and 1 Rupee 1/6d … and about religions: I can only consider agnosticism as a sensible choice.”

“12.11.45. My God! Am I tired. Flew 12 hours yesterday—down to Saigon and back in one day. Quite a strain. November 11th, too—Armistice Day for two wars. We thought of stopping the engines for two minutes at 11 o’clock, but decided against it. It’s a funny thought—you and everybody at home wearing a red poppy, counting the shopping days to Christmas, stumbling around in thick peasoupers, writing to the papers about the first frost and the last blackberry, the smell of bonfires in the pale chill air. And there’s us out here—10,000 feet above the swamps and jungles of Indochina, carrying food to the Saigonites, old man Sol beating down from a monotonous sky. Tokyo rumours are still persistent and everybody’s on tiptoe about future plans. I look deep into my beer glass every night, hoping to find a clue, but it tells me only that British beer is best. Yes, Japan’s going to shake us up! Get the blues out, practise tying a tie again, search the kit for studs and cufflinks. Where did I put them?”

The “rumours” were that the Squadron was about to be moved again—this time to Japan. There were actual dates mentioned: December, then January 1946, then later again. From early December I was doing less flying. Talk of “demob” was widespread but it seemed a long way off and one didn’t dwell on the possibility. I took on—and was allotted—a number of ground responsibilities which made a change.

“29.11.45. We’ve been back from Bombay a couple of days now and I’ve had time to sort myself out. We had set off for Calcutta on the 21st with 24 repatriates on board; stayed the night there. There was an INA demonstration staged by a Mr Bose—40 people killed. The next day we were off to Bombay. We were due to collect Dakota spare parts. They knew nothing about it. Stayed there three days and finally took back with us a load of toilet rolls and soaps for the lads. (‘Movements’ in the usual mysterious ways.) Bombay was a lovely city. We were billeted 100 yards from the beach; beautiful, sands, swam every day.”

“17.12.45. Last night I saw ‘The Way to the Stars’. It made me think of the most crazy moments a man could live through: how could any man—an ordinary man like myself—live through that and remain an ordinary man—like myself. It made me realise, too, how much I am missing; it made me think of you and home; it made me realise how cold I must have sounded in many of my letters for the last 6 months. It took me out of this mad little world of dust and jungle, of beetle and bug, of panic and peril, of alternating industry and inactivity. It took me for two hours back to Bury St Edmunds and Newmarket and Norwich and Aylsham. How selfish I must have seemed to you—wailing about my own personal misfortunes.”

“21.12.45. This has to be a very short note. I’m chosen as Defending Officer for an airman at a Court-Martial to be held next Friday, 28th. Knowing nothing of procedure, my head is swimming at the moment with facts newly acquired from the Manual of Air Force Law, the Manual of Administration, a Summary of Evidence—questioning witnesses and accused, learning Rules of Procedure. My first case! Add to this the fact that I’m acting in a couple of sketches on Christmas night (one as the ‘erk’ in our version of The Disorderly Room and the second as a Hyde Park orator).”

“29.12.45. Christmas is over. Unusual in one respect: I hope I never have another one like it—a little miserable. I must say, though, they did wonders with the food and drink. Turkeys and chickens were flown in from Bangkok and beer was plentiful. Served the airmen their dinner, a few drinks with the SNCOs and then our own few thousand bottles. Boxing Day was quiet—back to canned meat and veg. Japan date now 15th Jan.”

“07.01.46. At last some things are going right. I mean of course the court martial and the show. I must admit that that court-martial had me worried. It was almost like preparing for an exam. At least I’m happy that I’ve learnt one thing—that it’s no good swotting everything up the day before, just because you think you don’t know it. In actual fact you always do know it. For this particular ‘exam’ there was a complete day set aside necessarily just before the court-martial, that is, for the show. The show was given the night before. At the show (this is almost fictional) I unearthed a surprise defence witness!! It appears from the accused’s remarks to me afterwards that my defence—especially the last sum-up speech—had been effective. I was particularly happy about my confidence and the fact that I held the Court’s attention for 15 minutes or so at the end, and also for another 10 minutes for mitigation of sentence. (This is besides the examination, cross-examination and re-examination of witnesses.) I daren’t hope to get him off completely, because the charges are rather serious (drunkenness and threatening language to an officer) but I can justly hope that his sentence will be more lenient because of my remarks. I am happy. Now the show darling. The show went off very well indeed and it’s expected that we shall be asked to ‘tour’ it around the Rangoon area, possibly finishing up at the Garrison Theatre there. You’ll realise what a lift for the Squadron that is when I tell you who’s appearing there this coming week. For myself I’m busy writing a few odd sketches that I hope the fellows will add to their repertoire. About Garrison Theatre: ENSA has at last made itself felt around here, although we’ve still got to travel 30 miles along a dusty, bumpy road to see them. Last night and tonight Solomon is playing—unfortunately I can’t get in to hear him—lack of transport. Tomorrow and for the week Gielgud (!!!) is playing Hamlet and Blithe Spirit. I have tickets for tomorrow’s Hamlet. Wow! An experience I’ve always longed to have and here it is on our doorstep in Burma. Japan is off until 31st Jan.”

“08.01.46. It’s 11 pm. I’m writing this by the light of a very dim and unenthusiastic oil lamp. I’ve just had—believe it or ripley—a trying day. But at least a day in which something has been achieved. I’ve been, by truck, down the bumpy, dusty, 30-mile road into Rangoon, to Burma HQ. I collected, after much flattery, persuasion and charm (Hm!) a record player, amplifier, microphone, a couple of dozen dance records for the cinema and a programme, self picked—for next Tuesday—of serious music. The music circle will open on that day with the Mastersingers Overture, followed by some Chopin, Grieg, Albeniz, Puccini and finish with Tchai’s 6th. A programme at which yours lovingly will try to sparkle with a commentary. I could have a different programme each week but the journey is so tiresome.”

“22.01.46. We’re here at Hmawbi now for God knows how long. Japan postponed indefinitely; rumours of February, March, April.. and not at all. I’ve just moved out of my tent to another with my particular circle of irresponsible and slightly drunken cronies in it. We’ve spent the last two days reorganising the tent, and now sit back to admire our efforts with all the pride of a conscientious housewife. The sun is getting up—60 degrees altitude at midday; never any clouds. It gets hotter and dustier every day. Thank Heavens for the beer ration!—30 bottles each this month. Occasionally we get transport to take us to the Rangoon reservoir for a swim and dinghy practice. The rest of the time is spent on the camp … Rise with the sun, check shoes for scorpions, breakfast, busy oneself around the tent, chat with ‘neighbours’ in nearby tents, see to dhobi, and—if any—moochee, and danzi. (laundry, shoe-repairer, tailor). A cup of char, a game of table tennis, tiffin, write the odd letter, read the odd book, have a bath in boiling and rusty water (the pipe is out in the sun), shave, dress (just a pair of shorts), go to the Mess, collect mail (if.), play bridge or darts, evening meal (Machonichies), go to cinema if the film’s any good, drink, and so to bed, check mosquito net, try to sleep with the buzzing around one’s head—they got in anyway, squeeze your own blood out on the net, rise with the sun, check shoes … etc. See?”

I might have added a comment on the sanitary arrangements, but deemed it a trifle indelicate. We just dug ourselves a number of three-holers with a deep trench beneath and shielded decorously with hessian. What with the heat and the humidity and the continual usage, you can well imagine the conditions. One of our number had the misfortune to drop his wallet containing money from his back pocket. He had an interesting time retrieving it.

“30.01.46. Main topic of conversation: strikes in the RAF overseas. Stupidity. Principally types who’ve only just come out here and who in any case are stationed near the big towns. Should make an example of the ringleaders. I see there are strikes too in the USA: no steel, no Ford cars. A political cartoon has God chatting to a friend—‘Excuse me old man, I’ve got to bless America once more’.”

“07.02.46. It’s hot, very hot, and getting hotter. The mind’s weak, very weak and getting weaker. But strangely enough I’ve got a lot of interesting things on my hands at the moment. Welfare. The Squadron has moved its site about a mile and we are now messing with the Station HQ people. I’m getting more and more concerned with station welfare. Shows, newly elected music officer, on Entertainments Committee, film officer and God knows what. Just to give you an idea of how things are going, here are a few days’ excerpts from a newly opened ‘appointments’ book. 7th: 1100 Entertainments Committee meeting; 1700 Messing Committee meeting; 2200 Rehearsal for show; 8th: 0930 To Burma HQ Rangoon for music circuits; cinema records; film programmes; 1500 See film operator; 9th: am Station newspaper Committee meeting (associate editor) [my good friend Archie Elks, who was also there, reminds me that he received a prize for naming the newspaper “The Hmawbi Hmail”];pm Show at Boat Club Rangoon (‘Disorderly Room’); 12th pm Music circle. Add to that, collaboration in arrangements for a Bridge tournament and the possible production of Arsenic and Old Lace! All this is made easier of course by the fact that I’m no longer in an active crew, but a ‘spare’. I was offered a job as Operations Officer at Rangoon’s main airstrip (Mingaladon) but didn’t want it. I’d rather stay with the Squadron and go to Japan if and when the move comes off. Have just seen a quoted excerpt from an American newspaper: ‘We are smart people and we can prove it. But there are many other smart people in this world. The English [he means British] were pioneers in radar and atomic power. They were pioneers in jet propulsion. They invented the Bailey bridge. They invented the Mulberry harbour. They invented penicillin which saved thousands of American lives. Their aircraft are second to none in the world. Their achievements during this war are nothing short of miraculous. We think we saved the English. We’re not so sure the English didn’t save us.’ Well! So said the Cadillac Evening News: the most incredible thing I’ve ever read from American sources. Feb 3, 1946 was a day I and the rest of the lads will never forget. It was the day planned for the move of our tents up to this new site. Chaos ensued. Kit, beds, odd homemade tables, cupboards and all the paraphernalia of personal equipment (and my books) piled high on jeeps, trucks and anything else that was going. With, of course, our tents, poles, pegs, guy ropes, heaped higgledy-piggledy on top of them. We arrived safely at the new site and got straight to work erecting the tent and sorting out the kit. Worried eyes turned to the skies—clouds! Clouds which hadn’t been seen since November. Rain clouds. No, we said, it can’t be. It never rains at this time of the year. It’s dry, we said, from October to May, isn’t it? Was it hell. Down it came, well up to monsoon standards, the first rain for four months. The rain pelted down upon the red dust, churning it up into boiling mud, a wind blew, a ferocious gale that tore the tents down, pitched ‘em up in the air and threw ‘em half way across the field. What a melee. What truly beautiful chaos. There are some states of chaos which in the end do not irritate but amuse. This was such a state. It was laughable. The sun came out, the heavens sang the last movement of the Pastoral Symphony and we, dripping and sweating, started to patch things up again. I’m sure it will not rain again until May.”

“19.02.46. Uncertainty! Move to Japan put off till mid-April. At this rate I probably shan’t be going at all.”

“28.02.46. Here we go again with the vacuous ramblings of a near-demented mind. Scorpions are about these days in numbers—6 inch long ones, with two lobster-like claws and a poisonous tail. Can be most unpleasant if they sting with their tail. [The Indian bearers used to pour a circle of petrol around a scorpion, strike a match and watch with glee.] Saw yesterday what I think was a tarantula spider, a massive awful specimen about 4 inches across. One of our number who had been hitting the bottle a bit nearly collapsed. Some officers own their own pet monkeys—annoying when they start screeching. Talking of pets, I bought a parrot in Calcutta whilst on leave, a wee green one, with brilliant colour and natty looking tail. Took it up in the Grand Hotel to my room [a hotel commandeered for the duration] and left it to wander around as it wished. Found it a couple of hours later floundering in the lavatory bowl, panicking to keep its beak above water. Fished it out by putting a piece of straw between its teeth and watched it tottering around the floor—the most unhappy wet and wretched parrot you ever did see! It died a little while later, I’m afraid. Tomorrow is 1st March—no lamb and lion business here—it’ll come in like an oven and go out like an oven.”

“14.03.46. I’m quite sure that even under your snow and ice conditions you wouldn’t like a piece of this sun. It’s now 105 in the shade and still slowly rising every day. It’s only 8.30 in the morning as I write yet I’m sweating like the proverbial pig. I’ve got another job darling. Mess Secretary—keeping accounts and all that—mess bills, food and grog purchases and so on. No doubt I shall get intense satisfaction out of annoying all those who elected me. Music circle carries on. My brother Ken is now in New Delhi! After all the warnings I gave him of the horrors of the East, he goes and lands himself in a smashing place like that! In our little world, trouble. A crash yesterday. One man killed and three aircraft burnt out!”

“23.03.46. Strangely enough I’ve been working quite hard lately. This Mess Sec’s job takes up a lot of my time. Well, there’s been bags of excitement around here of late, one way and another. The first thing was a ‘move’ signal. You know the Squadron’s been waiting to go to Japan since December. One day last week in came a signal telling the Squadron to pack up and be ready for the first boat the following day. Absolute panic of course. Everybody marking kit ‘Japan’ and so on, everything in the way of equipment being crated up—never saw such a flap. Then of course next day—scrubbed. Now the Squadron’s not going to Japan at all—at any time. It’s being sent to Hong Kong—‘soon’. The other bit of excitement has resulted from Dacoit activity. The odd minor battle goes on on the strip these nights. Everybody careering around with revolvers last night at about 11 just after the bar had shut. Rather more of a menace than the dacoits, actually. The other night the whole load was swiped from one of our Dacoitas (Sorry!) I’m enclosing a photograph to illustrate the insanity around here. Football match—‘Muttonheads’ v the ‘Whisky Woofers’. I was the ‘Mayor of Hmawbi’ sweating in greatcoat, chain of office and top hat—kicked off and presented cup. Chap on my left has ‘Press’ ticket in his bushhat.”

“30.03.46. Coincidentally, a signal came in 3 days ago, granting me an Extended Service Commission. It was two years ago that I put in for a Permanent Commission and now this has come in. An ESC is for 4 years only and then you’re likely to be slung out on your ear. Looking for a job at 28 compares unfavourably with having one at 24. And, of course, accepting one would mean another two years out here. It’s exactly one year tomorrow since the ‘Winchester Castle’ left the Clyde River in a Scotch mist. It’s been an extraordinary year. Cairo hospital in April. Central Provinces 17th May. Rangoon 19th May. Back to Central Provinces. Rangoon—Bangkok—Saigon 3rd September, And more than 6 months at Hmawbi! Another two years? I’ve refused it of course.”

In fact, I changed my mind. I decided NOT to return to the Bank—the job now seemed so mundane. I looked at the employment situation back home in the UK and didn’t like what I saw. After writing that last letter I had an agonising period of thinking about the future, something I hadn’t been used to since 1941. I came to the conclusion that the peacetime RAF would be an interesting career and that the only way to get started on it would be to accept the ESC. This I did.

That decision implied, of course, that I would be travelling to Hong Kong with the Squadron to take up a new task.