I travelled with many other members of the Squadron—not by air but by sea—routed through Singapore and thence to Hong Kong. Except for bouts of weather, the journey was a pleasant and comfortable rest.

“06.05.46. SS Salween, Singapore harbour. We’re anchored off Singapore after what could definitely not be called an uneventful journey from Rangoon. First night out we ran smack into a cyclone—100 mph winds, colossal seas, lightning all round us—and it lasted 6 hours! Sleep impossible, thrown out of bunk, terrific crashes around the ship, people shouting, thank Heavens I’m a reasonable sailor. Now here at Singapore it’s raining steadily. Hundreds of British ships here—encouraging. And hundreds of British cars crated on the docks, just unloaded from UK.”

“15.05.46. 96 Squadron, RAF Kai Tak. We docked two days ago in Kowloon Harbour. Between Kowloon and the island of Hong Kong are warships, transports, cargo ships, ferry boats, Sunderland flying boats, all imaginable craft peppering the water. Hong Kong itself makes the most marvellous view of any city in the world. On our first night in Kowloon we attended a party on the top floor of the Peninsula Hotel which is now an Officers’ Club. Our quarters are in a large 3-storeyed house, ultra-modern, with bathrooms! Kowloon itself—wide streets, trees, thousands of shops, cinemas, restaurants. Can you imagine?—this is Heaven after Burma! After 8 months of sand and dust and tents—this! Know the phrase—‘Having wonderful time’? Yes.”

We were based at RAF Kai Tak, an airfield with a rather short runway dangerously close to Kowloon on the mainland. The winds seemed most of the time to demand approaches for landing over the most densely populated area of Kowloon, with high buildings just off the western end of the runway. Woe betide any pilot holding off for too long before touchdown: he’d find himself in the drink at the other end. Airmen’s quarters were mainly in Nissen huts on the airfield, but the officer aircrew of our Squadron were billeted in a requisitioned house in the suburbs of Kowloon.

“27.05.46. We’ve been enjoying the Parisian Grill on the island (first-class filet mignon) and the cinemas and the clubs. But prices, we understand, are now 10 times what they were pre-war and, after the initial flush, we’re having to be careful with money. Now—real news. My commission has been confirmed from Air Ministry. I gather I’m the only navigator in SEAC with an ESC. I’ve applied for an Advanced Nav Course back home at Shawbury: a pass carries with it a 1st class civvy nav ticket.”

But for some months I was not to have an opportunity to keep fresh with navigational skills. I did no flying of any significance until early September of 1946. In the meantime I was allotted responsibilities on the ground.

“01.06.46. Work is mostly welfare. Concerned for instance with an airmen’s dance tomorrow night: fix a band, a piano, a microphone, extra food, extra beer, money to pay for it, invitation cards, guests, transport, decorations, lighting, chairs, glasses and . well you see what I mean? Then also I’m ‘Demob Officer’ dealing with Demob problems. Ironical. Plus a bit of study for the hoped for course. State of mind? Strangely sad right now—many of my oldest friends are leaving for home next week.”

“09.06.46. 110 Squadron RAF Kai Tak. The Squadron’s changed its number from 96 to 110. I’m one of only 12 who can say that they were in at the birth and death of 96. I’m still waiting for that course.”

“02.07.46. I’ve put in for ‘mid-tour’ leave and for ‘End of War’ leave; then perhaps (rumoured) the overseas tour will be down to 2 years total which would be OK (US) Tikh Hai (Indian) Ding How (Chinese) and Wizard (RAF) … I’ve got three jobs going at the moment—navigation training, welfare and demob officer. This month we get taken off Indian payroll and are put back on UK rates, with UK Income Tax. It’s a bit of a shock. We ‘enjoy’ a local overseas allowance of HK$3 a day which equates to 3s 9d, enough to buy one tomato juice.”

“08.07.46. It’s prickly heat season again! Talked to the Doc about it. Couldn’t do a thing for it. ‘Just keep cool and don’t rush around. Stay in a cold bath and keep under a fan’. It would be nice to comply with just one of those instructions.”

“09.07.46. The typhoon season starts very shortly. The newspapers keep everybody well-informed as to position, speed and direction of every typhoon in the China Sea. A shipload of British Hong Kongers is expected in from Sydney, whither they’d been evacuated at the outset of war. Their reported comments: ‘I shall be so glad to get back; I hate Australia; it’s so tiring looking after the children; I shall have my amah brush my hair for an hour just for the sheer luxury of it.’ They must imagine that all is the same as they left it—prices, houses, whites’ social position. Not so—because of a shortage of European houses through bombing, looting and requisitioning, they are to go initially to huts in the Stanley concentration camp … A little story of manners: Station ZBW is Hong Kong’s radio. Two RAF corporals were borrowing records from ZBW to put on a couple of jazz programmes each week at the Kowloon other ranks club. They did it so well that the writer of a letter in the Hong Kong Mail wanted to thank them both for their professional job before leaving for UK. He added that ZBW would do well to follow their example.. The next week ZBW announced that it would no longer be possible to supply further records to the RAF corporals …”

“14.07.46. Did you see what that arch-cynic, arch-egotist Thomas Beecham had to say about Hollywood? ‘Hollywood’ he said ‘is a universal disaster compared with which Hitler, Mussolini and Hirohito are mere fleeting trivial incidents.’ Well! … (Nice for him that millions have fought to ensure that they were fleeting.)”

“15.07.46. It’s Monday. A typhoon is expected to hit Hong Kong Wednesday morning. All crews are to stand by to fly the aircraft out tomorrow…”

“16.07.46. The typhoon has just been reported on the northern tip of Luzon Island, about 250 miles from here. It’s moving WNW at 15 knots, extends over a large area and at its centre has winds up to 120 mph. All serviceable aircraft are being flown out to Hainan and other points south …”

“18.07.46. (10.00 hours) It foxed everybody. It slowed down and lost 24 hours. We’re on the outskirts of it now. The wind is roaring down from the hills to the north of the airfield at about 50 mph already. The sky is obscured, low clouds race past the hills and heavy driving rain makes it impossible to see more than a couple of hundred yards. But this is just the warming up stage—we shall be nearer the centre this evening. Ships have left their wharves, naval craft have sailed south, all junks and sampans have just disappeared and our serviceable aircraft flew off yesterday.

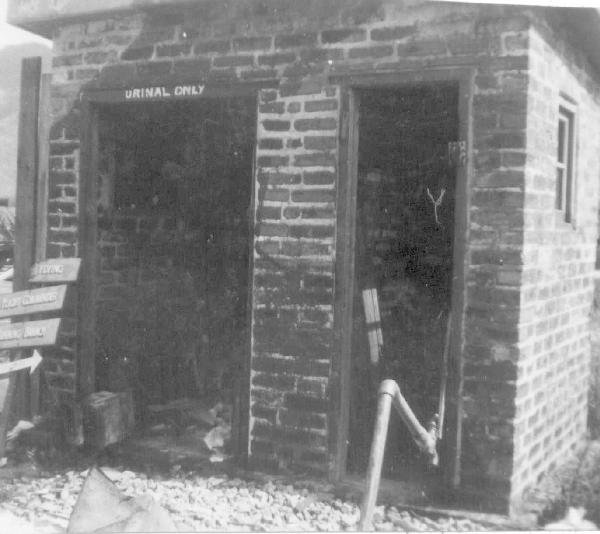

“(Midnight) Never seen anything like it. Frightening is the power of the elements when they really get cracking. Trees uprooted, trucks overturned; on the airfield, flight offices destroyed, papers forms books typewriter, everything, disappeared; the whole place flattened; Nissen huts swept away, corrugated iron sheets flying through the air; aircraft that had to remain (Dakotas and Sunderlands) overturned; wireless masts down; naval station flattened, two ratings killed.”

“20.07.46. All details in previous letter confirmed. The max windspeed was 106 mph and the centre passed 20 miles away. The flight building (housing two flight commanders, navigation and signals sections) was lifted up into the air and smashed down again into rather a lot of pieces. Five Dakotas were written off—one was seen 12 feet in the air momentarily—and two Sunderlands tipped up. The only building left standing was a stone-built lavatory, with a copy of Kings Regulations floating in the pan. Played a 6-hour session of bridge, winning all of 12 rubbers, 11,000 points. (‘Is this a record?—constant reader from Tunbridge Wells’) …”

“28.07.46. I am incensed! Henry V has been cut to ribbons. No sign of Falstaff, or Mistress Quickly, no Fluellen, no eve-of-battle soliloquy; the English camp before Harfleur cut, the French camp before Agincourt cut, the Duke of Burgundy’s cut. !!. No doubt next week ‘Cobra Woman’ starring Maria Montez—the goddess of American erotomania—will run in its entirety. But there was more. The film critic in the next day’s newspaper obviously hadn’t seen it, but just copied from a film magazine : ‘George Robey’s floating appearance should puzzle the puritans.’ (He wasn’t there) … And the peach—‘The Agincourt battle scenes compare favourably with anything that Bogart, Cagney, Flynn or Wayne have ever done as far as action is concerned.’ Good grief!”

“03.08.46. As Demob officer I’ve had to prepare talks on the postwar RAF and deliver them in an exuberant fashion to airmen aircrew and ground personnel. As Welfare officer I’ve had to balance the books and the cash of the airmen’s canteen. So you see—that’s why I can’t write every day. I failed to get into the June quota for midtour leave … A thought—apropos of nothing—have you considered that a pointed remark will usually be blunt?”

“04.08.46. It’s Sunday and half a dozen of us went 30 miles into the New Territories to play golf. Twice round the course!. I’ve never played it in my life. The sum total of balls lost was about 20. The Chinese caddies were not all that helpful because they got a dollar for them from the next suckers who came along. I can’t say that I’ve completely Cottoned on to the game (Ooh! Sorry).”

“05.08.46. Today—August Bank Holiday—is a day off for the RAF. Not for me. I’m Station Duty Officer. Which means that I’m the CO’s representative for 24 hours. I have to take action on any important signals that come in; and check up on the mepacrine registers of at least 3 sections on the station. Having checked the Officers’ Mess register, I find 17 haven’t signed for 5 days and they include—the Groupy himself and two medical officers! Close the bar at 2300 hours—and, oh yes, a special job tonight—search the sergeants’ quarters for a whore suspected of making frequent visits.”

“06.08.46. Those who are waiting for demob are brassed off—there are no releases for officer aircrew in the latest promulgation. It’s a matter of conjecture whether everybody will be out before the next war opens up …”

“07.08.46. A ship called the ‘General Gordon’ arrived the other day from San Francisco with a cargo of Jews (and Jewesses.) They’re all displaced persons and for that I feel for them. But when they start writing to the papers, complaining of the lack of accommodation (doubling up in hotel rooms!) while British servicemen take up space in residential houses, then my sympathy begins to wane. One outspoken serviceman at least has replied that they should show more gratitude to those who recovered the colony for them to return to. Peace, brethren, peace!”

“19.08.46. BOAC are starting to set up here at long last. The Yanks, the Chinese and half a dozen private companies have been using Kai Tak already for some time. This starts the usual crop of rumours about our not being needed here now. Did I tell you that BOAC during the war was interpreted in Bomber Command as (i) Britain’s Occasionally Airborne Civilians or (ii) Bastards Overseas Avoiding Conscription. Cruel …”

“22.08.46. I see from Time magazine that British films are falling foul of Hollywood’s morality code, now run by a Mr Breen who took over from Mr Hays. E.g., The Wicked Lady—‘lowcut Restoration costumes worn by the Misses Lockwood and Roc display too much cleavage, the Code’s trade name for the shadowed depression dividing an actress’s bosom into two distinct sections. The British are resentfully reshooting several costly scenes.’ [The Wicked Lady was shot largely at Blickling, near Aylsham.] Rex Harrison’s The Rakes’ Progress is changed to The Notorious Gentleman so that it would not be mistaken for a documentary on gardening. At least Time had the commonsense to be cynical about all this, and quoted our own New Statesman & Nation: ‘America’s artistes may strip / The haunch, the paunch, the thigh, the hip, / And never shake the censorship, / While Britain, straining every nerve / To amplify the export curve, / Strict circumspection must observe. / And why should censors sourly gape / At outworks of the lady’s shape / Which from her fichu may escape? / Our censors keep our films as clean / As any whistle ever seen. / So what is biting Mr Breen?’“

Time also had the good grace to acknowledge, humorously, a protesting letter that I wrote to them.

“23.08.46. I see from an old newspaper article that H G Wells has died. Did you know that long ago he wrote his own epitaph? Simply … ‘I told you so.’ Unfortunately the old boy’s grey matter was getting a bit warped towards the end—he was inclined in his last years to write and talk rather a lot of drivel …”

“26.08.46. A very full weekend indeed. On Saturday afternoon there was a cricket match between the officers and the sergeants. I went along as scorer: despite my statistical efforts, the officers didn’t win. That went on all day in a high sun. Sunday began on the golf course. Another full day of lashing furiously, often futilely, at a small white ball with a mashie or an iron or a … oh, a host of ‘em—and then spending half an hour looking for the damned thing in the long grass; then buying them back off the caddy on the next hole. Enterprising, these Chinese. Back from there in the evening, along to see a football match between officers and sergeants. (We won.)”

“01.09.46. My accounts satisfied the auditors … Now a change of activity. There’s a shortage of aircrew and I’m required back on flying. Got to keep my hand in. I’m crewed up with a very experienced pilot and we shall be carrying passengers and the odd VIP around.”

Yes, I was back in the air for a period, flying with Flt Lt Will Hill. I made 10 flights with him, mostly as navigator, sometimes as second pilot (very steady to fly straight and level in good weather—steady enough for a navigator!). All the flights carried passengers between Hong Kong, Saigon and Singapore. The route became a routine. But there were technical problems.

“09.09.46. We’re at Changi airfield. Something went wrong—an oil cooler or suchlike. We expect to leave within three days. We stopped off at Saigon. The French seem to have achieved little since the re-occupation a year ago. It makes a glaring contrast with Hong Kong. HK, with British interests flowing back in again, is well on the way to complete recovery; but Saigon, with French influences only, has stood still. The lights are still on only 2 or 3 nights a week, the Annamites are still giving trouble, food is scarce. We have to call in again on the way back—it’s a half way point.”

“16.09.46. Still at Singapore! We’re still waiting for another aircraft to bring in the spare part our aircraft lacks. None has come in for ten days. There are rumours of two more typhoons at HK amd more unserviceability at Saigon. So we’re having an enforced holiday—swimming, sunbathing, chess, bridge, the Straits Times crossword, the camp cinema in the evening. I’m eager to get back—for the mail that is bound to be there, and also to ensure that the various Squadron affairs that I control are not in a state of chaos …”

“27.09.46. I’m annoyed. Firstly because I’m struck down with yet another fever; secondly, because there’s been a bad crash here and if it’s been publicised in UK without names, God knows what you’ll be thinking. The fever is what they call dengue, temperature up, temperature down, and so on. When it’s down, I can work out that the sum of your birth year, my birth year, your address, my address and the old Ford 8 number, MINUS 9515, equals zero. Did you realise that? …”

“08.10.46. I’m out! And fit and well. Now I have to be ‘categorised’ as a navigator by a team of experts travelling around SEAC. So—exams in three days time! …”

“13.10.46. Got an ‘A’ in theory, but little recent practical flying will bring the total down to ‘B’ … Now I’ve got to ‘do’ the other navigators. And there’s the Welfare accounts to catch up on.”

It was B+ (recommended VIP).

“18.10.46. Yesterday a lot of my pals went home on demob. It was rather depressing. Courses: there are two ‘career’ courses for navigators: the ‘Advanced’ which I’ve already put in for, and a higher and longer one called the ‘Specialist’. My examiner says he will recommend I go on it; but the rules are that you take the one before the other. We shall see.”

“21.10.46. I’m off to Singapore tomorrow. It’s an important trip for me. When I arrive there I have to hand in my log to the Navigation Officer at Air Command South East Asia so that it can be checked and—here’s that word again—‘categorised’. It seems I’m the only potential VIP navigator on the Squadron. We’re carrying a couple of Generals and the Air Commodore.”

“28.10.96. We’re back in HK. Counting both ways we spent 3 nights in Saigon. I like practising my Francais in Saigon. We were looking for the Cercle Sportif (for a swim) and I asked a Frenchman in my best schoolboy French where it was. He said in impeccable English ‘Oh yes—it’s just up there on the right’. Cigarettes are scarce in Saigon: we were strolling down the Rue Catinat and a Chinese type came sidling up to us and whispered ‘cigarettes?’ Our wireless op turned to him, nonchalantly waved his hand and said ‘No thanks old man—just put one out.’

“30.10.46. We’ve got a new CO—a vast improvement—and he’s decided that I’ve had the wretched thankless Welfare job long enough. He’s dished it over to someone else, for which hearty thanks from me. And there are rumours that I shall get my VIP category shortly, flying bigwigs from ACSEA. You know that VIP stands for Very Insipid People … HK has been a very lively place lately. Some of the Chinese community want the British to leave. There have been riots. We were confined to billets for a short time. But we’ve done so well in reorganising HK since the Japanese surrender that most Chinese—particularly the Chinese millionaires—realise we’re the best of all the evils they could think of.”

“05.11.46. So the Republicans have got in. Sometimes I wonder whether I fully understand the American constitution. For one thing, politics only means one thing—graft. And it doesn’t matter what one says in an election campaign. What matters is : ‘How many more votes can I get by denouncing British policy in Palestine (let’s see now—what is all that business about anyway?’). ‘Now boys what sort of dirt can we plant on our opponent?—Woman trouble?’ … The Republicans have gained a large majority in both the House and the Senate. Truman—a Democrat President—stays in office until 1948! Surely a hopeless position …”

“07.11.46. A strange thing in today’s China Mail. The crossword was as it should be but underneath it were today’s answers and tomorrow’s clues. I turned to the racing columns to see if they’d got today’s results. We completed tomorrow’s crossword without knowing where the black squares were. We rang up the Editor and asked if he’d like the answers. He was vastly amused.”

“10.11.46. Tomorrow there’s a cricket match between the Mess and the Squadron airmen. It’s a full day off—Nov 11th. I don’t approve of the sentiment but if it means a holiday by all means have Armistice Days. Let’s go back in history and dig out a few more wars. Pile up enough wars and we shan’t have to work at all …”

“15.11.46. I’ve got my VIP category and am all set to fly in a VIP crew. First such flights coming up soon …”

There were to be 16 such flights before the end of the year—and before moving base again—embracing not only the well-trodden HK-Saigon-Singapore run, but also Bangkok again and dear old sticky Rangoon. The quality of the aircraft was a cut above the strictly utilitarian version we were used to.

“26.11.46. I’m at Singapore at the moment. Got here by devious routes. We flew an Admiral to Rangoon via Bangkok. The aircraft was special for VIPs. Pastel creams inside, tables, lamps, armchairs, divans, a galley, bags of good food—in short, a humdinger. There was just our crew of 4, the Admiral and a Petty Officer steward. The trip to Bangkok was smooth, flying over desolate tracks of Indo-China (first time direct). Almost looks like Conan Doyle’s Lost World. Jungle and rock mountains jutting straight up. One could almost imagine pterodactyls flying around down below … Rangoon was very sticky compared with the winter cool of HK—mosquito nets again! Went straight to bed on arrival. Up at midnight; take off at 2.30 am for a direct route from Rangoon to Kai Tak. So we had an 8 hour flight plus 2.30 hrs on the clock. This meant we had 3 hours of night flying—long time since I’d done that. Navigating by the stars for the first part of the flight. Then dawn.! What a sight! Draw a straight line from Rangoon to HK and you’ll find that it crosses a range of 10,000 foot hills—the southern end of the ‘hump’. Fogs form in all the valleys and where there was a valley higher than another, the fog could be seen flowing out—spilling over -–from the higher to the lower. Just like water … We had a clear day at HK, and then set off, via Saigon (brief stop only) to Singapore with 6 passengers: Chief of Naval Staff, HK, and some of his personal staff. Perfect weather—very good flights. And that brings me up to date. Still here at Changi, Singapore. Due to return end of the month …”

“29.11.46. We leave Changi tomorrow, to return to HK, this time via Bangkok, carrying 9 different VIPs. And it seems I shall be at HK only one more month. There is a posting in the offing to Singapore …”

“04.12.46. Cocktails last night with Lord and Lady Tedder. Seven rows of gongs—wears his wings somewhere round the back of his neck. Mr John L Lewis, in the States, is nothing more nor less than a dictator, causing chaos with his strike …”

“06.12.46. What a crisis! UNO and the Russians off the front page. Lewis and his miners gone to the crossword page. England is in full retreat! Another Dunkirk! Australia wins by an inning and 300 runs. Good Gad Caldecote, what is the game coming to! Nobody’s been talking about anything else for the past week. Eager groups of listeners, faces drooping with gloom, crowded round the mess radio. The feeling in the air is worse than September 1939. Dear, dear.”

“09.12.46. Today we took a British Board of Trade Mission team to Swatow and back. Had to pick them up in Canton first, just north of here. On arrival at Swatow, met by a local band, greetings from the town’s businessmen, off to the British Embassy for a bit to eat, then to the Mayor’s residence for cocktails. Everybody drinking—except us—the crew. Somebody had to stay sober. Then round the town in a fleet of cars—lace and embroidery factory, pewter factory, etc; trade discussions; hasty beetling back to the aircraft. I talked to the members of the team: about Britain’s trade prospects, China’s eagerness to buy, and distribution of British films. Must be difficult working out exchange rates. The Chinese National dollar has just inflated from 15,000 to the £ to 23,000 to the £. The posting to Singapore. It’s after Christmas: I shall be flying with the flight commander of 48 Squadron VIP flight. 9 of us will be sailing on the Arundel Castle—very leisurely.”

“22.12.46. Chaos again. On the boat on 27th, the day after Boxing Day. Concentrates the mind. New address when we get there (New Year?) will be 48 Squadron RAF Changi, Singapore.”

Another year—another ship—and another place; and despite the promise of VIP flying, once more I would be working on the ground until May.

“01.01.47. 48 Squadron RAF Changi SEAAF. 1947! So I’ve had my last Christmas abroad. On Christmas Day we had a comic 20-a-side football match against the sergeants. The rules were chaotic: handling of the ball was allowed, thus turning it into an American football-cum-rugby scrimmage; and nobody should take advantage of the goalkeepers by shooting when said goalie was having a drink. Consequently no goals were scored. We followed this up with the ritual of serving the airmen’s lunch—more hilarity; then buffet and bar for us. Boxing Day started very late; a party in the evening had special significance for me. I was embarking next morning. The journey lasted four days. The ship was packed—we had no more space to ourselves than I had on the US troopship going to New York in 1942. At least on board was also an ENSA team that I’d got to know quite well in HK … New Years Eve saw us in dock—hot and sweaty and irritable. The Army people were difficult. I wanted to change HK notes—no, can’t be done—only Sterling. What was strange about coming from HK with HK money? Then on disembarkation, I had four bags; carried two down the gangplank; went back up; refused re-entry, only once down the gangplank!; so I went round the back of the gangplank and climbed up the framework. There is a lorry waiting for us types who are going to Changi. But wait—Changi is 15 miles East. We’re new arrivals so we’re taken 30 miles North first, to the mainland to book into an Officers’ Transit camp. We book in. The next minute we book out. Then do we go to Changi. No, we don’t. Back to Singapore first, then to Changi. Finally to 48 Squadron Mess. 1947 enters and I’m holding your photograph in my hand.”

“03.01.47. Things are grim. I’m not keen on (1) the Mess (2) the food (3) the station (4) the distance from Singapore (5) the mail situation (6) the accommodation and (7) my deepsea kit—haven’t got it yet! Ah well—it’ll all come out in the wash. HK spoilt us.”

“07.01.47. ‘Settling in’ at Changi. The station is very large and spread out. Much shoe leather consumed getting around. Accommodation poor—three of us in a barely-furnished room. Prices are high in Singapore. The HK dollar was worth 1s 3d; the Malayan dollar is 2s 4d but buys no more. The weather is very wet—average 8 inches a month. Flying—apparently only one VIP trip a month …”

“12.01.47. I’m going by air tomorrow to Penang for a three week holiday …”

“17.01.47. On leave, Penang. Similar setup to HK. The airfield’s on the mainland—Butterworth. Penang is the island, joined by ferry, the harbour, the hill … The island certainly is a beauty spot (it’s been chosen as a leave centre). The beaches are lovely, palm trees, sand, rocks, marvellous swimming (phosph0rescence at night). I’ve been round the island, visited a Buddhist monastery, botanical gardens and a snake temple, swam in a waterfall and travelled to the top of the 2,500 ft hill by funicular … I had my fortune told by an Indian. I learnt that I’m coming home this year—a good guess, most people are; that I’m going to marry one girl and keep another (expensive!); that I shall live till I’m 84; and that I shall have 7 children (seems that mepacrine does NOT sterilise.) All this information he obtained, mark you, from my RIGHT hand—the one that’s disfigured by the accident at Blickling!.”

“03.02.47. 48 Squadron, RAF Changi SEAAF. I’m back at Changi only to discover they’ve sent all your recent mail to Penang!”

“12.02.47. I seem destined never to stay here for any length of time. All those with ESCs are to take, some time, a ‘Flight Commanders’ course—Admin and all that. I’m being sent on one starting 27th Feb and it’s in Ceylon. It lasts 6 weeks, entirely ground work, i.e. classroom stuff. Drill every morning at 6, nine hours lectures every day; and exams at the end of it. I welcome it—I’ve always wanted to see Ceylon; and it’ll be an opportunity to get the grey cells working smoothly and efficiently again. It’s just ironical that I get the course I haven’t been asking for. With all this, it seems inevitable that I shan’t be home until the full 2 and a half years are up in August or thereabouts. I’ve been unlucky. They want applicants for the Nav course but only if they have a YEAR left. Now I’m not eligible. [Catch 22!] And the reduction of tour to 2 years will only apply to married types.”

“17.02.47. The weather here is becoming unbearable again. Up comes my third tropical summer. On March 21st the sun will be dead overhead here. Right now it’s 90 F and 98% humidity …”

Very different from UK. We knew well from letters and newspapers that the home country was suffering its worst winter for many decades with snow and ice almost continuous from the beginning of the year until the end of March. It was a hard time for a country still desperately trying to recover from the rigours of the war; fuel was short, transport was difficult, rationing was just as tight as during the war, the economic situation was dire … And there was I writing about high temperatures and humidity …

“24.02.47. Brother Ken has a spare-time job in Delhi as an announcer with All-India Radio; good, he could do with a bit of extra cash in a place like Delhi. How about what you might call a “shaggy rat” story? Siam had a plague of rats. They called in a rodent expert to deal with them. He got 50,000 bahts to do the job. He offered a tenth of a baht (say half a penny) for each rat’s tail brought into his office. In three months he had 500,000 tails and all his money was gone. But there were still a lot of rats about. The farmers, good buddhists all, caught the rats easily enough but didn’t kill them. Their creed says it’s wrong to take life—any life. So they’d been cutting off their tails and letting them go free. Not only were the older residents of the rat community running around without tails, but vigorous new generations were growing up without tails. There were some farmers who had started to breed WITH tails so they could resume making money! Actually, this happened some generations ago, but the story has been recalled in the Singapore press because the Siamese Government has just requested urgent assistance in dealing with rats who are despoiling rice bags due for export to India and Malaya.”

“05.03.47. Katukurunda, Ceylon. At last I’ve arrived for this Admin course. Yesterday morning I left early in a Sunderland flying boat and we flew via Penang to Koggala, a flying boat base at the southern tip of Ceylon—a total of 11 hours flying. From Koggala it was a 40 mile bus journey to Katukurunda—the road following the coast northwards, past rocky beaches and mile after mile of palms. The course timings are slightly different from what I’ve already told you—drill or PT at 6.30, then lectures straight through until 1.30 pm. Nobody works in the afternoon. But there are evening exercises to do. Billets are good—a room each. The Mess is magnificent, comfortable and lavish. The bar is tremendous, the food is good—delicious curries. All things considered, I can stand 6 weeks here. I mean to work hard …”

“20.03.47. It’s becoming imcreasingly obvious that this is just what the old brainbox wanted. There won’t be many cobwebs after 6 weeks of this. Drills, PTs, lectures, demonstrations, taking charges, orderly rooms, courts-martial, etc. I managed to see Colombo before the course started. A very pleasant, clean city. It has a lot of bookshops! And the swimming here along the coast is wonderful, beautiful sandy beaches. Some days the waves are 10 feet high: once I hit the wave incorrectly, turned over and over, deposited on the shore with a belly full of sand and salt. I gather that all the beaches will be out of bounds when the SW monsoon arrives. Last week there was no wind. Good place to see stars …”

“28.03.47. I’m still alive—but with a frenzied eye and a fevered brain. Been up till one o’clock the last two nights swotting for exams … Two more weeks to go and then back nice and slowly, by boat!”

“05.04.47. I’m the only flying type on this course—all the rest are ground officers. But I’m holding my own—1st in the Personnel exam, 2nd in Law & discipline, half way down in Org & Admin … The swimming is beginning to get much more dangerous now—20 mph back current towards each wave—steady! James Agate in the Tatler votes A Matter of Life & Death one of his Worst 10 Films! Unbelievable!”

“20.04.47. The course is over—great success. It’s now very hot indeed and sticky—just pre-monsoon. We now wait for a ship, the Strathnaver, to sail us back to Singapore in about a week’s time …”

“28.04.47. 48 Squadron RAF Changi SEAAF. As soon as I’d put my bags down somebody came up to me , handed me the Mess keys and said blandly that I was now Mess Secretary. It so happens that my predecessor has left the accounts in a shocking condition and there’s an audit in three days time … And I’m Station Duty Officer on that same day. Heigh-ho.”

“14.05.47. Now at last I have time to get you up to date. The Strathnaver was a goodly ship (P&O, 23,000 tons); a pleasant 4-day voyage marred only by the fact that we were bundled in 150-strong with brand new Army one-pippers who nowadays seem to have lost all sense of personal discipline and dignity. Is it the sudden release from England that turns them into a bunch of squealing adolescents? Captains (my equivalent) had cabins of course. Those on the boat coming straight out from UK had harsh comments : ‘Don’t whatever you do go home now—it’s deadly.’ (!!) Since I’ve been back jobs have simply been piling up on me : they’re going to cash in on that course. Officers’ Mess Sec, Officer i/c Sergeants’ Mess, Officer i/c a barrack block; and I’ve been on an Audit Board for the past week. Some time soon I might do some flying!”

The Mess Secretary’s job I looked upon as a nice challenge for a particular reason. Mess bills are always to be paid by the 10th of the month following the month under account. One would often be frustrated by the delay in the bills being placed in one’s cubby-hole. Sometimes they wouldn’t reach it until the 9th: irritating. I resolved to put an end to that. On the last day of the month, I made sure that I had all the relevant data by the time the dining room and the bar had closed. With the metaphorical wet towel around the head, I then went off to the quiet of the Mess office and worked steadily right through the night. The Mess bills were in every member’s cubby-hole by dawn on the 1st. Then I went to bed.

“My Advanced Nav course is now definitely off. It seems Air Command HQ discussed my case : they’re very sorry I’ve been messed about but they are ‘really short of navigators out here and can’t afford to lose me four months early’. Well, well—short of navigators—and I haven’t flown since December! Anyway, as a consolation prize I’m getting an official letter from the C-in-C asking them at home to put me on the course with no waiting when I’ve had my home leave. Books: I’ve just read Harris’s ‘Bomber Offensive’. Very invigorating, and extremely provocative. He regards his (i.e. Bomber Command’s) enemies in the following order—Royal Navy, British Army, German Air Force, Politicians and Civil Service. His book mentions, of course, many of the raids I was on … And ‘No Bed for Bacon’ by Caryl Brahms and S J Simon (a Bridge columnist by the way), a very witty little book about Shakespeare and his having a writer’s block. [Note 2000: cf. ‘Shakespeare in Love’, screenplay by Tom Stoppard.] And ‘Reading I’ve Liked’, an anthology of prose selected by Clifton Fadiman, literary critic of the New Yorker. In a very wise preface he warns against the dangers of over-reading. He recalls once making a martyr of himself by reading nothing for 3 months: says it had a wonderful purging effect, getting rid of non-essentials in the grey matter and leaving the pure grain. The idea horrifies me—might miss something important going on. For instance—Time: ‘This is still a good country. A month in the Britain outside London is enough to convince anybody that there is a lot of vigor and promise left in the people who live the real life of this Island and who do its real work. There is still a future.’ Well said.”

“18.05.47. Had an argument with the Squadron CO a few nights ago (he’s VERY right—feudal baron type). It got so heated that we both took our rank badges off in order to continue. No hard feelings afterwards—he calls me a ‘political sentimentalist’.

The CO was in fact Wg Cdr Gordon-Finlayson, a man of most impressive size and bearing and, as I discovered later, a member of a distinguished military family. His brother was a 3-star General and knighted. I rather think our G-F considered that he was slumming in a backwater job commanding 48 Squadron. Anyway, he and I had a very healthy respect for each other’s arguing powers and what appeared at the time to be inadvisedly heated was in retrospect quite good fun. Later, he was to ask that I accompany and navigate him home when we were both repatriated. (See September.)

“Universal Productions are to obtain shots for a film to be called ‘Singapore’ with Ava Gardner. They needed aerial shots—48 Squadron supplied them. I’m flying again—navigator for our Flight Commander. A couple of days ago we flew to Kota Bahru, picked up Sir Edward Gent, Governor of Malaya, and his staff, and took them to Kuala Lumpur (‘muddy water’), capital of the Malayan Union. Dapper, quiet and embarrassed by Army formalities and parades, etc, in his honour.. This coming week we shall be off to Saigon and Hong Kong. Reports have it that French Indo-China’s hinterland is getting hostile to Europeans; we mustn’t land anywhere but near a large town.”

It was good to get back in the air again. From mid-May until the end of August, I flew 41 flights around the familiar South East Asia area, plus certain new destinations in China—Nanking and Shanghai. My pilots were Sqn Ldr Alford and Flt Lts Best, Coster and Hill. On half a dozen of the flights I acted not as navigator, but as 2nd pilot—and steward! Of Best (“Tiny”) I shall say more later.

“28.05.47. Lots of flying now. We took a Japanese Reparations Team to Hong Kong. Stayed a night in Saigon and two nights in HK. Saigon is still as chaotic, still as disorganised as it was 6 months ago. Hong Kong, always a g0-ahead-for-recovery sort of place has changed out of all recognition even since 6 months ago. Prices down, shops fuller, 250 new English taxis in the 6 months; and the old 110 Squadron Mess still as happy and carefree as ever. BUT 110 is to be disbanded and everybody’s to be sent to Changi! They won’t like it, but we shall be getting some good types down here. Got back last night, and then was wanted again with another pilot this morning to help out Sir Edward Gent once more—took him from Kuala Lumpur to Kuantan on the East coast. Next week we return him to KL. And soon after that we’re scheduled to take some Economic, Foreign Office and UNO advisers to Shanghai and Nanking. More new places!”

“19.06.47. We left Changi bright and early on the 7th with all those advisers. At Saigon we learnt that there had been a case in the Chinese quarter of bubonic plague. Hong Kong had heard of the case and we—crew and passengers—had to be inoculated for plague. The Doc said ‘you can’t fly immediately after this’ so we had to stay over in Saigon. And what a day it was. We met an American group—oil types—drinks in the US Consulate—drinks with the Captain of a US ship in port at the time—found myself below decks discussing philosophy with three intriguingly intellectual American merchant sailors. (Shades of ‘The Long Voyage Home’). Freshen up in our rooms at the Majestic Hotel, then off to a party arranged in our honour at an American house. Rather the worse for wear, the next morning flew to Hong kong and were accepted with our plague chits. A quiet evening. And then, morning after that, set off to Shanghai—weather perfect, saw the ground all the way. But on arrival the wind was too strong and off the runway; we therefore had to press on to Nanking and after 7 hours airborne, we landed there. The capital city of China. A dump, like a dirty little village, dusty, filthy, smelly. We—the crew—went to stay with the Air Attache. The next day, after our economic passengers had said all they wanted to say, over to Shanghai. A much more international and interesting place of course: big hotels, skyscrapers, lots of traffic—but the currency! 2,000 dollars for a newspaper; 500 for a box of matches; and a meal for three came to 125,332 dollars (the British Embassy paid for that!). Back again to Hong Kong, this time through some rather bad weather: we didn’t see the ground or the sun for five hours, but we came out smack over Hong Kong nevertheless. (Hm. Sorry—lineshoot.) They told us that we wouldn’t be allowed to return to Saigon until 6 days after the inoculation! This meant two enforced days at HK. (Bought a lot of books.) Then finally to Saigon and Changi, smooth and uneventful, to be told we were to be off again the following day to take a General Galloway from Kuala Lumpur to Kota Bahru and the day after that, the reverse journey. My pilot on the trips in this letter was a very large man Flt Lt ‘Tiny’ Best. A great pilot, but now he’s going home, so I shall be switching pilots again.”

That phrase above “through some rather bad weather” was a deliberate understatement. I had no wish to alarm Patricia. What happened was this. All flyers know the dangers of flying inside Cumulonimbus (“thunder”) clouds. In their most vigorous state they are very great in height—from near ground level to the tropopause; they contain the most violent up and down drafts and light aircraft caught out in them have been known to be taken to the top and tossed out, with fatal results; there are huge waterdrops and hailstones; there is lightning. Often Cb clouds are isolated, individual storms which can be seen in advance and skirted. But between the two Tropics—Cancer and Capricorn—depending on time of year, there can be an absolutely solid barrier created along an East/West line by what is known as the Inter-Tropical Front. The day was 12th June 1947: the sun was virtually at the Tropic of Cancer, Latitude 23 degrees North. Hong Kong is at 22 degrees. We hit trouble somewhere north of Hong Kong as we were flying southwest from Shanghai. There was the line in front of us. It was solid. It was black. It was dangerous. We couldn’t possibly get over it in a Dakota. We daren’t go down to try to get under it—there were mountains. We had to plough through it at 9,000 feet, our most common altitude. “Tiny” Best wrestled with the wheel for a good hour; he put the flaps down, he put the undercarriage down, in order to reduce our speed to a minimum. I can’t recall the precise airspeed but it was well under 100 kts. We knew that we were being buffeted by up and down drafts of the same magnitude. Windscreen wipers in front of Tiny were well-nigh ineffectual in providing him with a clear view of the blackness ahead. Occasionally everything would be brilliantly lit up by a blinding flash. Inside the cockpit behind Tiny and in the passenger section, all was chaos. I had given up trying to retrieve my tools of the trade; they kept scattering all over the place. The passengers behind us were looking decidedly queasy. As I say this went on for an hour: at the end of it, the sweat was pouring off Tiny. But it did come to an end. We came eventually into clear calm air with only stratus below us. When we landed at Kai Tak we all did what the present Pope often does. We kissed the tarmac.

“By the way, we brought down with us from Hong Kong some Indian Army people—a very intelligent bunch. One of them, summarising the different factions in India quite dispassionately, said:—‘The Hindus think, but do not act. The Moslems act, and think afterwards. The Sikhs act, and don’t think at all …’”

“30.06.47. A bit of excitement … Monty’s here. That means everybody up at HQ goes on soft drinks for the next week, I suppose. Landed at Changi the other day—the place was a mass of Military Police. Very little man—Monty; he was dwarfed by all the other Army types around, paraded in their Sunday best to meet him …”

“19.07.47. As I write we are at Tengah, about 30 miles west of Changi to pick up Lord Killearn in the morning to take him to Delhi for a meeting (not publicised) with the Viceroy. You may realise why I’m excited—I shall be able to see my brother Ken. Now—there’s an awful lot of preparatory work to be done in the navigational line for a trip of this sort …”

“03.08.47. Yes, I’m still at Delhi. We didn’t expect to stay this long. The noble Lord has been getting around a bit more than he intended. It seems he has finally refused the job being offered to him by Jinnah—the Governorship of what is to be East Pakistan [now Bangladesh]. It’s been very good seeing Ken again. He’s dying to get home; he has prickly heat rather badly. Honestly, you wouldn’t believe it, I’m looking forward to getting back to Singapore—the climate is murderous here in Delhi. The monsoon’s failed and they’ve had only a third of the expected rainfall. But at least Ken has All-India radio: I’ve been over there a couple of afternoons playing records—lovely, in cool air conditioning.”

It had come to my ears that my good brother Ken who was by now also in the RAF was based in New Delhi and through some strange quirk of fate was announcing on All-India Radio. I arranged to meet him at Palam airport one day. I can’t remember how we communicated but he was there on time. He had cycled from the centre of the city. We hadn’t met for years. The airport was almost deserted in those days—nothing much was flying. All of our crew and Ken had a whale of a time putting away a number of beers. At some point in the discussion we decided it was time to give Ken a little ride in the Dak. So off we went circling Palam for about an hour, with Will Hill surprisingly more talkative than usual. Now it so happened that Ken was scheduled to introduce a programme on the Radio entitled The Week in Retrospect. Whatever the time of start was, he wasn’t going to make it. After landing, Ken set off on his bicycle, weaving uncertainly towards the city. Needless to say, he was half an hour late, and he told me later that All-India Radio was completely silent for the half hour of his planned programme. Much later when we were sweating further east he played Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloe as a request from me, which was nice of him.

“17.08.47. Now that His Lordship has at last decided to return to Singapore (via Bangkok and Penang) a little more news for you about conditions in Delhi. Everywhere there was an incredible air of expectancy, with 15th August approaching. Flags were flying, some tricolor with the Asoka wheel, others the green Moslem with crescent and star. No more ‘God Save the King’ in the cinemas; instead the caption ‘Jai Hind’ flashed on the screen. And they all took as much notice of that as they used to of the King. So—they’ve got it now. We didn’t see much evidence of trouble in Delhi itself—Calcutta and Lahore seem to be the main riot spots.”

This was a time of great historical interest. After 163 years of British rule, India was to be free, but in three parts—India, West Pakistan and (unsustainably) East Pakistan. Over the months following this letter, millions were to migrate from one side of a border to the other, and half a million were to die in sectarian fighting.

“In Bangkok, because of the importance of our renowned passenger Lord Killearn, we were swept along with his social whirl—cocktails at the Embassy and the Siamese Air Force and others. A lot of Thai whisky was consumed: it’s truly the most amazing drink in the world. It’ll get anybody pleasantly happy in no time at all, but leaves no hangover whatever—cf. “Soma” in the Brave New World. My first impressions of the Siamese remain unchanged—they’re the happiest and most progressive bunch in the East. They’re the only ones undominated by a European power and yet they try to follow the European example more than any other country.”

“10.09.47. Been very busy—balance sheets, inventory checks, audits, ready to hand over, and at the same time, packing for the journey home at last.Left Glasgow 30th March 1945 … 17th September 1947 will leave Changi. By air, that is, the Squadron CO and I bringing a Dakota back home to UK for disposal. Allow about 10 days or so …”

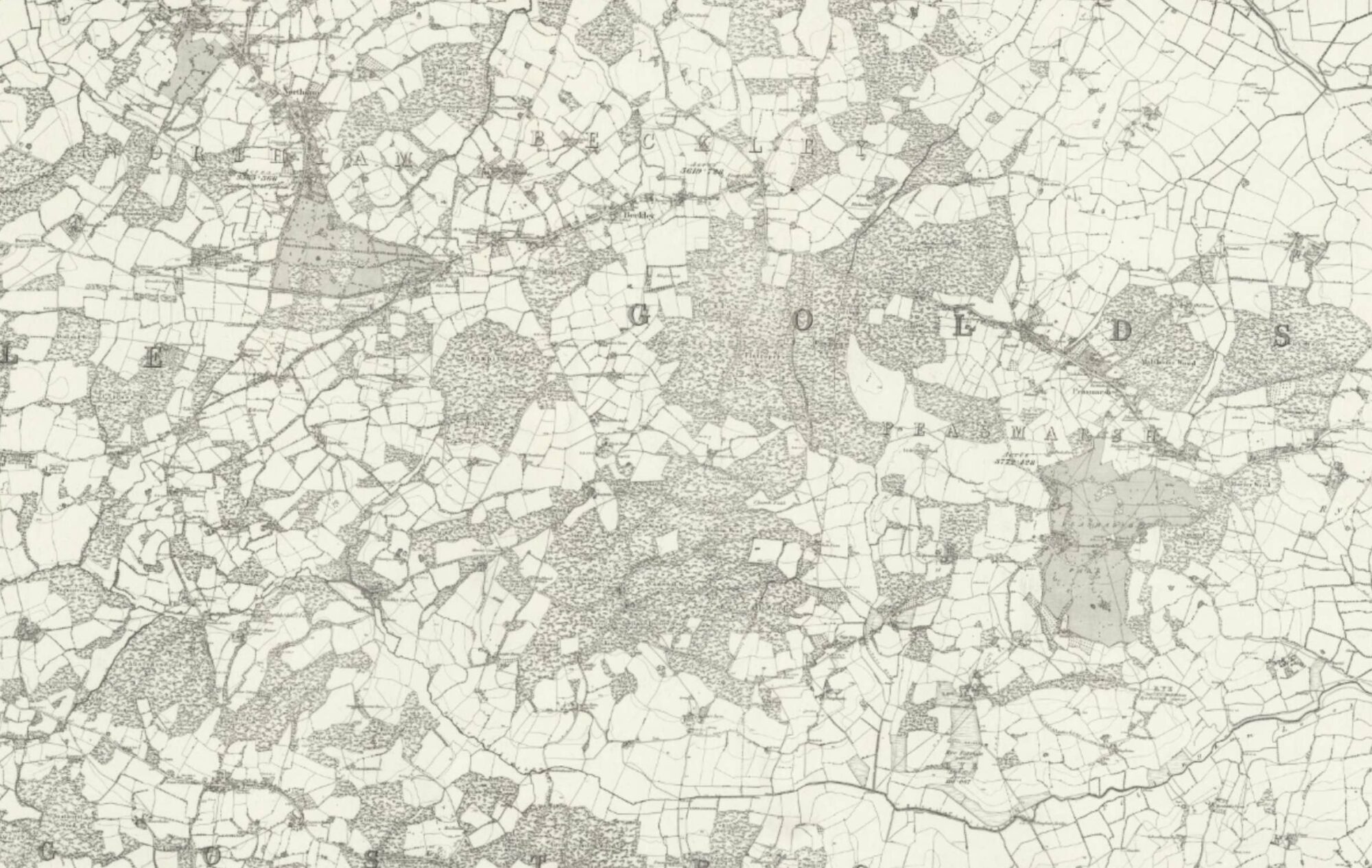

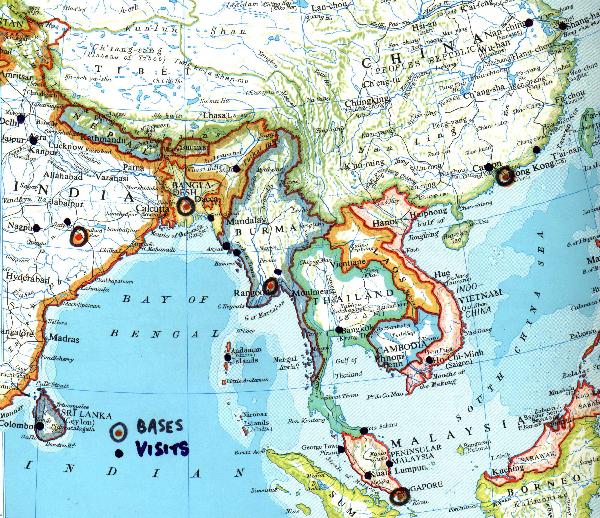

Operation “UK DAK” was the name given to the idea that repatriating crews should bring back with them to a holding unit in the UK aircraft which were now being taken out of the front line. It was reckoned that one pilot and one navigator could do the job—and of course they were right—no problem. Indeed, it was a very pleasant task, particularly knowing that as every day went by, one was nearer home. So it was that the large-as-life character Wg Cdr Gordon-Finlayson and Flt Lt Furner brought home Dakota KN570 to a Maintenance Unit at RAF Kirkbride. Mind you, it was a slow process. The range of the Dakota couldn’t match today’s 747s! From Changi we flew to Butterworth; thence to Rangoon; Calcutta; Delhi; Karachi; Sharjah; Habbaniyah; Aqir; El Adem; Luqa; Istres; Lyneham; and Kirkbride. Thus it was 13 flights in 12 days. The good Wg Cdr chose not to overnight stop at Butterworth, Calcutta, Sharjah and Aqir but to spend two nights each at Delhi and Luqa; his navigator had no problems with that.

At Lyneham, the first entry into the UK, the Customs man was extremely harsh with my bag of silks, satins and other textiles. He charged me a lot of money, taking no account whatsoever that I had left the country well before the war ended and here I was returning after two and a half years abroad.

On 29th September the Wg Cdr and I officially handed in the Dakota to the MU and then went our separate ways. We had got to know each other extremely well on the journey, but that was the last we saw of each other. I travelled home by trains. My first overseas tour was at an end. UK looked glorious in an Indian summer. After “disembarkation” leave with my folks and with Patricia, the next step would be the promised Advanced Navigation course.