After two and a half years in the Far East, home leave was a delight. I shared the time between Southend (family and friends) and Norwich (Patricia and her family). My first thoughts before all else were that Patricia and I should plan our lives together. We had known each other for seven months before I went overseas, but we then corresponded for the two and a half years with hundreds of letters each way. We knew each other’s likes and dislikes, each other’s interests and opinions, each other’s hopes and fears. We quickly became engaged and fixed the wedding date for 7th February 1948, which I was able to calculate would be immediately after the Advanced Nav course finished. It would be another 50 years before I was to discover the coincidence of my father’s birth date.

The country that I had returned to was still in dire straits economically. Many items were still rationed—foodstuffs, clothing and petrol in particular. Cars were rare—few could afford to run them. Most travel was by public transport, which was deep into the process of nationalisation. Television, which had had a very brief and unique beginning in 1937, was not yet restarted. Any “luxury” items—and gramophone records were so classed, let alone perfumes, watches and cameras—were subject to what the Chancellor of the Exchequer was pleased to call “Triple Purchase Tax”. As one example, this meant that a two-sided shellac record, playing just seven and a half minutes total of music, was ten shillings (50p), a quarter of my earlier weekly salary at the Bank. Today, 1999, that amount of time of music costs about a penny in 1947’s values. Nevertheless, hard though the living was, Patricia’s father (Dick) satisfactorily made all the necessary arrangements for the wedding and its celebration meal.

With those arrangements in hand, I set off in late October to RAF Shawbury, near Shrewsbury, home of the Empire Air Navigation School. The word “Empire” has a strange olde-worlde sound about it these days, but in 1947 it was still in use in many different spheres. The EANS did indeed host pupils and guests from the Empire, from all those countries who had given us military and moral support during World War II.

I had much else on my mind at that time. I was mindful that my present Commission was limited and that I had to succeed in upgrading it to a PC—Permanent Commission. Only thus did I have a planned future which would enable me to support a wife and family. [In those days it was very unusual for the wife of a professional man to take employment for herself.] I therefore worked hard to prove myself on the course and, hopefully, to be worthy of a posting which would give an opportunity to excel. As a backstop I paid six guineas to the University of London for my Inter BA certificate, with the intention later of working for an external BA in Maths Honours.

I wrote many letters to Patricia during the course. A few excerpts might be of interest:

“Have you ever heard of D C T Bennett? Pathfinder king as an Air Commodore during the war, now in British South American Airways. He’s reputed to have written a book on navigation while on his honeymoon. I don’t think I shall emulate him …”

“Time magazine has recalled that some of Churchill’s speeches were converted into Basic English. Thus ‘blood, toil, sweat and tears’ became ‘blood, work, body water and eyewash’ …”

“Letter from Porthminster Hotel (St Ives) confirming our reservations—‘May I remind you to bring ration books and also your own towels as we much regret that we are no longer in a position to provide any.’ Reminds me of a cartoon—hotel receptionist to bellhop: ‘Take Mr & Mrs Brown’s luggage to 514 and Colonel Smithers’ and Miss Robinson’s ration books to the office’ …”

The course went well: the outcome was good. By 3rd February 1948 (still a Flt Lt, age 26) I was judged to be a fully qualified Navigation instructor. My resultant posting, after a month’s honeymoon leave, was to RAF Middleton St George, near Darlington, known as No 2 Air Navigation School. Flt Lt and Mrs Furner were to arrive on 1st March.

But before that there was the grand event—our wedding ceremony. It was beautifully done, Patricia and Jack pledging their troth “until death us do part”, the warmth of families and friends contrasting the cold of the February day. I felt so grateful to my mother, who had made the superb dress for Patricia from material I had brought back from the East, and to Dick, my father-in-law, for all his arrangements which ensured success. My brother Ken was Best Man and Pat’s sister Betty was principal Bridesmaid.

We left Southend by train in a flurry of confetti and two hours later booked into the Cumberland Hotel opposite Marble Arch. On signing in, Pat (let’s shorten her name now) wrote Patricia Donnelly, then embarrassed, crossed the surname out and overwrote Furner. “Not to worry” said the receptionist, “we’ve got lots of those this evening.” Oh dear …

It was a Saturday, that 7th of February. We stayed in London over the weekend, enjoying a concert and a film, making love for the first time and walking on a cloud. On the Monday morning, we boarded a train to St Ives, carrying with us, of course, the requested ration books and towels. We enjoyed an idyllic three weeks there. Then it was time to move north—way north. I remember counting our belongings on York station as we were waiting for a connecting train: two cases each, a wind-up gramophone and two boxes of 78 rpm records. On arrival in Darlington Pat stayed in town to look for somewhere to live and I travelled to the airfield by train to report for duty. By the end of the first day Pat had taken a rented room (just one!) at No 2 Langholm Crescent, Darlington, our 1st home. The room was our bedroom—a fairly small one at that—and we had the use of part of the kitchen. There was no bathroom; the WC was outside. I vividly recall spending one Sunday morning re-roping the bed frame. It was clear that we couldn’t stand these primitive conditions for long, particularly when, in about a month, Pat confirmed that she was pregnant. Two months after arrival, we were able to move into a shared rental with another couple from Langholm Crescent—all four of us moved to 19 Stanhope Road, our 2nd home. They had the lower floor and we the upper, much more spacious and civilised. We—that is, Pat and I and later Peter, our first son—were to remain there for a year. Not so the other couple.

Now here’s a curious thing. Many times in our early married life, other couples who lived closest to us had relationship problems. It was almost as if we were a jinx to them. To start with, the couple who had moved with us, Norman and Aileen, had a tumultuous time together. Norman was married, but not to Aileen; they had frequent rows; we, with all the wisdom of our few months of marriage behind us, tried to act as arbitrators; she became pregnant; a more bitter row than usual ensued; Aileen was in tears; Pat comforted; Norman and Aileen both left in very distressed states. All this time Pat was progressing through her own pregnancy: she had a craving for radishes, so much so that I allocated a small space in the back garden to producing radishes every six weeks or so. The birth of Peter went well and within a few days of the birth, she was producing so much milk that she could spurt it right across the room—extraordinary and wonderful.

Norman and Aileen’s place in the half-rental was taken by an RAF Fg Off and his wife—Mac and Dina. She was Lithuanian and found the English language difficult to cope with. They had frequent rows; one of them culminated in Mac stalking off down the street in high dudgeon, his dignity wounded to some extent when a sudden gust of wind blew his RAF cap off, causing both Dina and Pat, watching, to chuckle. He did finally return (after about three days) but by then we had decided to move again; this time to the upper part of a house owned by Denry, a very nice chap who lived on his own and had only men visitors. It was a couple of blocks away—88 Greenbank Road, our 3rd home, just a short walk from the Hospital in which Peter had been born.

It was thus well into 1949 before the opportunity of a Married Quarter came our way. These were days of having your name on a waiting list—so many points for length of marriage, for number of children, and that sort of thing. There were MQ building programmes being pursued on most permanent stations. At last, after our first three addresses, a Quarter was offered to us at Middleton St George and we duly “marched in” to our 4th home. Pat was at first most alarmed by that phrase, supposing that she was to be caught up in some military pomp and ceremony, until I assured her that this was service jargon for checking the inventory and condition of the house. It would be further checked on “marching out” when we were posted.

The brand new Quarter was adequate: certainly we had more space than we had been used to. But the final condition of Quarters was always determined by the acceptance of cheapest tenders—in every respect. There was no central heating, just a fireplace. The floors were composition which in the early days continually sweated. The windows were, of course, single glazed and ran wet with condensation. The consolation was that we would not have the responsibility of trying to sell it! Our next door neighbour was another Flt Lt and his wife, and—yes, you’ve guessed it—they had a row and split up.

I wanted more than anything that Pat should be happy with her first impressions of life in the RAF. Already she was in a whirl with a young baby and so many changes of home. Then there was the important matter of my work and status on the station: that also was relevant to her state of mind. Unfortunately, Middleton St George was an unhappy station. When I look back now to those days so long ago, it was only a combination of youth, ambition and resilience which kept us both going through the two years at Middleton. But it was a bad start for this lovely girl who wished to do her best to support her husband’s career. So—what was the problem?

There were a number of factors affecting morale at No 2 ANS. First and foremost, the Station was being run by deadbeats—senior officers who most definitely were not going anywhere career-wise. They were all pilots and I suspect they reckoned that they’d been shunted aside from the main career stream by being tasked with the running of a navigation school. The Station Commander was a Group Captain C-, a surly man who was hardly ever seen except in Station HQ. I should explain that the whole of the School—the raison d’etre of the Station—was outside the main camp—buildings housing many classrooms and lecturers’ offices. At any time there could be half a dozen courses coming through, some of new entrants, others of experienced navigators who were being “refreshed”. NOT ONCE was the Station Commander seen in this area; he never visited it.

There were two Wing Commanders on the Station: Wg Cdr Flying (Surname T-) and Wg Cdr Admin (Surname O-). The senior Engineer was a Sqdn Ldr; the senior lecturer (OC Ground School) was a Sqdn Ldr navigator. Wg Cdr Admin was a stuffy chap who also saw no point in taking an interest in the Navigation School. Wg Cdr Flying was a pleasant extrovert type who loved to organise “escape and evasion” exercises by dumping us on the Yorkshire moors with a map and a torch in the middle of a dark night and tasking us with getting back to base before dawn without being picked up by “police”; but in other respects he let his enthusiasm run away with him. For instance: there were rehearsals for a Battle of Britain flying display within the resources of the Station—Wellingtons and Ansons. He was keen for a Wellington swooping low over the airfield and dropping supplies in full view of the crowd. On one of the rehearsals, one of the packages caught itself around an obstruction under the aircraft: warning enough that there was risk with the idea. Fortunately, the pilot managed to land the aircraft safely without further problem. Wg Cdr Flying insisted that all was well, the drop could go ahead on the big day. There was a fairly large crowd of spectators, including families of participating crews. One of the packages fouled the tailplane surfaces and controls. The Wellington went straight into the ground in full view of the spectators. The aircraft was destroyed. All the crew were killed. The court-martial which followed the mandatory Court of Inquiry found the Sqdn Ldr Engineer guilty of negligence. Wg Cdr Flying’s judgment was not questioned.

It so happened that, on this unhappy station, I was still trying to further my application for a Permanent Commission. There was one occasion when the Station Adjutant, a toffee-nosed and pompous Flt Lt, called me in my office and told me I would be wanted for an interview with the Station Commander, at a stipulated time, in respect of the application. This was important for me. Check all aspects of dress, shine shoes, cap on at the right angle, gloves at the ready—in a word, bull. I was in the outer office well in advance of the time. I waited, and waited, … and waited. Finally, after about an hour, the Station Commander swept through the outer office without a word; the Adjutant said he was too busy. I returned to work. I was not called again for interview. [Twenty years later I was a Station Commander: I never forgot the discourtesy I suffered that day at Middleton St George. Never would I treat the lowest ranking airman in that way, let alone an experienced and decorated officer.]

Outside in our separate establishment of classrooms—the Air Navigation School, the name, mark you, of RAF Middleton St George,—and whilst other parts of the RAF were busying themselves with the Berlin crisis and consequent airlift, we instructors carried on with our tasks. And they were no mean tasks. Let me quote a figure. For my first year and perhaps a bit beyond, I was asked to “volunteer” for Meteorology lectures. There was no one else who was remotely interested or capable of taking the job on. The civilian met. man on the station was not established to lecture to navigators under training—only to keep tabs on local weather conditions and advise fliers accordingly. Anyway, I accepted the task and got to work. A complete course of Met instruction amounted to about 50 lectures. The arithmetic of the number of courses (groups of trainees) combined with the length of their time at the ANS meant that, at peaks, I was delivering 35 one-hour lectures per week. There were times when I was literally dashing between one classroom and another. The first series of 50 lectures was hectic: it was wet-towel time in the evenings in order to be able to keep ahead of the trainees. Later, of course, by reason of constant repetition, it became much easier and, indeed, even became fun with rapidly increasing confidence and the insertion here and there of suitable and relevant humour. The title “Meteorology” came to embrace also Climatology, with fascinating descriptions of tropical storms, monsoons, strangely named winds around the world and comparisons of wettest and driest, warmest and coldest and all the other factors involved with the atmosphere. Then the only aids for the lecturer were blackboard and chalk: what one could do now with projectors and the appropriate software!

In my second year I was assigned to different tasks—away from specialisation in one subject to the overall control and management of particular Course Numbers, thereby having to present widely varied lectures. By this time my experience at talking to people and holding their interest had provided more and more confidence in speaking to a prepared brief. Although there was little or no interest from Station HQ, the chaps who were running the Ground School could understand well the work load and how it was being shouldered. They were, first, Sqdn Ldr Rush who sadly was killed in an Anson air crash; followed by Sqdn Ldr Tony Jillings, who remained a close colleague and friend for many years after. Fortunately for me, there was also an independent and objective supervising organisation which was taking note of my efforts. Flying Training Command employed a roving team of officers whose sole responsibility was to vet the lecture technique of all the Command’s instructors. They would aim to visit each training station at least every six months and would sit in on lectures to make assessments, rather as School Inspectors in the education field vet teachers. I know it sounds immodest to say so, but they were always fulsome in their praise for my lectures. Their reports almost certainly had something to do with my next activity after Middleton St George.

In addition to her own domestic concerns, Pat was mindful of all this. She shared in my worries, in my occasional humiliation, in my exhilaration of sometime success. Add it all together with the domestic circumstances and you can see that the first two years of marriage were hard for her; she could be excused for wondering what she had got herself into. However, we celebrated our second wedding Anniversary in grand style—at least, for those days. With Peter at just over 1 year old being cared for by Pat’s parents, she and I stayed in London for a week and went to five theatres in a row—“Streetcar named Desire”, “Hi-de-Hi”, “Annie Get your Gun”, “Harvey” and the International Ballet. How we afforded it, I just do not know.

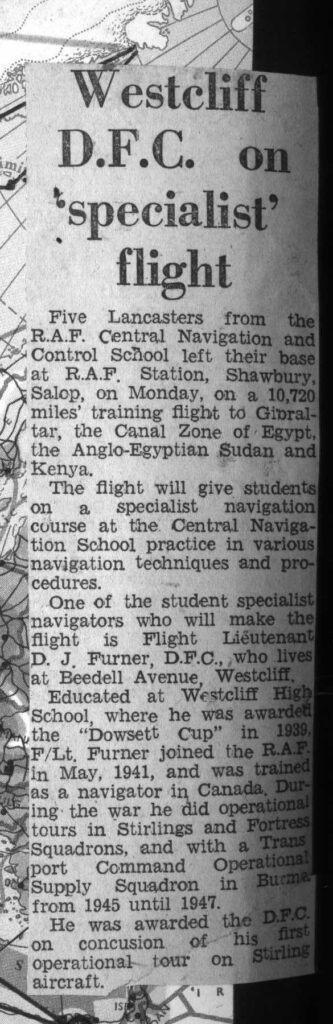

A little later that year (1950), I was told that I was to attend the Specialist Navigation Course starting in August—a very prestigious course lasting eight months which every career-minded navigator wished to get on. Before that happened, there was a bit of flying at Middleton in carrying out the duties of managing various courses; and a few flights in association with ICI to see whether there was any future in seeding clouds with silver iodide pellets to make it rain in chosen spots. The trials were inconclusive. We could never tell whether the rain underneath us when we descended under the cloud would have, or would not have, fallen in any case—interesting, but strictly academic. (Curiously, somehow of other these ineffectual trials became the subject of a 2001 report in the major newspapers: it was suggested that similar trials, later in 1952, could have caused nine inches of rain to have fallen on Lynton and Lynmouth. This was an absolutely preposterous idea. I sent a letter to the Telegraph to say so: they chose not to print it but at least their weather correspondent used the same phrase.)

Again before the Course happened, there was another move, believe it or not : it was decided that No 2 ANS should move from Middleton to Thorney Island, near Southampton. Thus, at the end of May 1950, I made one train journey looking after a batch of airman; Pat and Peter made another which was arranged for families. The trains were routed straight through. The three of us met at a small cottage in Denmead (“Peartree Cottage”, our 5th home) where I had arranged rental accommodation—very basic once again, with a WC at the bottom of the garden. Thorney Island was a much happier place, the senior officers were good types and interested in our work; I was asked to navigate the Station Commander on certain visits. My lecturing continued but not for long.

At the end of my time at No 2 Air Navigation School, whilst the newspapers had screaming headlines about the invasion of South Korea by North Korean forces, we took a holiday near Weymouth in July, relaxing until August 1950 when we were off again to Shawbury for me to attend the Specialist Navigation Course. We rented our 6th home at 73 Woodfield Road, Shrewsbury. Shawbury by now had dropped its “Empire” title. It was now the home of the Central Navigation and Control School running courses of varying depth and sophistication. (Indeed, the word “Empire” was disappearing in every sphere—the Imperial Bank of India had changed to the State Bank of India.)

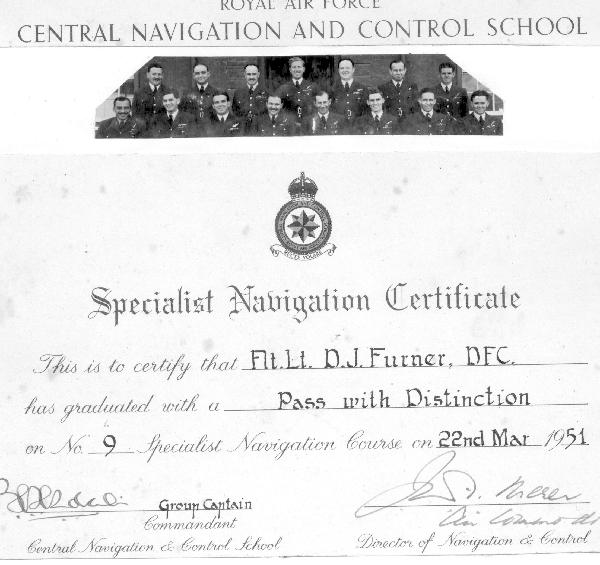

The Spec N, as it was familiarly known, was intended to equip career navigators, and a few pilots—a dozen of us in all—with the expertise to hold down any senior officer planning task. It went into every aspect of air navigation in far greater depth than hitherto, taking account of all air roles and paying particular attention to new equipments and new techniques. In the classroom we probed into the detailed mathematics of astronomy, the statistics of bands of error, the physics of radar receivers; in the air we flew in high latitudes without magnetic compasses, making use of all navigational and ground approach aids then available, and on “pressure pattern” technique which relied on differences between radar altimeters and pressure altimeters; away from Shawbury we were given guided tours around most of the aero-space (aircraft and equipment) companies in the UK. We navigated with various techniques to Gibraltar, Fayid, El Adem, Malta, Keflavik, Jan Mayen Island and Greenland; we navigated as Bomber, as Coastal and as Transport; we searched the Atlantic for weather ships. Each of us had to finish the Course with a thesis of one’s own choosing. I remember mine was entitled “The Minimal Flight Path” which sought to establish a technique of using winds at all possible levels to follow a route in the shortest time; it was not relevant to high speed jets but to large slow aircraft, airships and balloons. (Those in the 1990s who are following the current fad for ballooning around the world have no doubt come to the same conclusions that I did, but complicated by the need to avoid China.)

It is interesting to note that today’s equivalent course (in 2002) carries with it the award of MSc to graduating students.

I quote from a letter I wrote to Pat from Reykjavik:

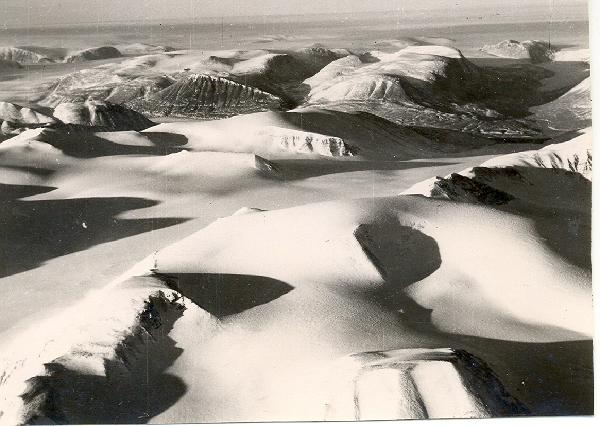

“15.03.51. Took off in the Lancaster at 04.00 GMT, climbed to 10,000 feet and set course. First, remember what we were wearing. I had on thick long underwear underneath normal battledress togs, then a thick sweater, then inner flying suit that looked like a junior quilt, then an outer suit, two pairs of gloves, flying boots, and in my bag another pair of socks and a balavclava helmet in case they’re needed. In addition must carry into the aircraft a sextant, a Mae West, a parachute, a harness and all the navigation kit, equipment and charts.

“We crossed the northern Iceland coast in the dark and ploughed on through a lot of cloud until the sun slowly came up on the eastern horizon. The aurora display slowly gave way to marvellous reds of the sunrise and the grey clouds underneath us gradually dispersed. The crescent moon continued on its day long journey around the sky—at this time it was up for a full 24 hour period in such high latitudes. The island of Jan Mayen came up at 7 o’clock, a gigantic sheer rock jutting 8,000 feet out of the sea. We turned here to go north to hit the Greenland coast. Fixing position with the sun and the moon, we struck the coast at 9.30. For two hours now the ice has been thickening up on the sea, and now there are no more lanes or cracks in it. The sea is a solid white sheet, jagged in parts where glaciers down from the interior have crushed their inexorable way down to the coast, clear in patches where the ice is more newly formed. It’s difficult even to tell whether it is sea or land. White, white everywhere, with little ridges and lines where the ice is more ruckled. It’s cold down there—probably colder in fact than we are at height. There’s nothing living down on that ice—it’s a wilderness—possibly like the appearance of much of our hemisphere in the last Ice Age. It looked exactly as Sibelius’ Swan of Tuonela sounded—empty, vast, cold, unwelcome, impressive.

“This was just the beginning. We reached the coast. Here the sights became even more wondrous. There were no clouds, the sun was now circling the southern sky at a low altitude, and the visibility was literally unlimited. The air was crystal clear—no smoke or dust or sand—just clean clear air that no man had ever polluted, nor many men even breathed. In such conditions did the sights of Greenland show up to the best advantage—rocks and mountains and snow and jagged ice shining and scintillating in the pure air and the sun. Most of the coastline leapt up from the sea ice to thousands of feet, mountains of hard brown rock, one side covered with centuries of deep snow, the other swept clean by the polar winds. No even pattern here—the work of a crazed sculptor—jagged jutting rearing diving, it seemed difficult to believe that they’d been like this for aeons of time and would be for just as many more in the future. Fjords of thick ice cut their tortuous way into them and glaciers of slow-moving ice crushed and smashed and battered their way down to meet them. Further inland the mountains reared higher and ever higher, 7,000, 8,000, 9,000 feet, until the mass of the interior became one vast plateau of solid ice—unmapped, unexplored; frigid, unwelcome.

“We took photographs—some oblique from the side of the aircraft, others vertically down from the nose. We photographed a glacier for the use of a future expedition, so that they may more easily assess the structure of the ice and its dangers, and find a possible route.

“And so for another three hours we flew southwards down the eastern coast of Greenland. The weather remained fine, the terrain still presented the same rugged magnificence. It went on for 400 miles more—mountains and snow and ice and glaciers—frightening clarity, awesome vastness and cold horror.

“At one o’clock we finally left the coast to cross the Norwegian Sea back to Iceland. For another half hour the ice persisted, till it began slowly to break up. Fissures appeared and cracks ran their crazy way through the glassy surface. Ice flows surged and rocked gently on the sea, icebergs floated serenely towards the south to bring hazard to the ocean routes of the north Atlantic. Then the ice was all behind us, the sea looked its familiar self, the white horses reappeared in the string northerly wind. By two o’clock we were over the north coast of Iceland: barren rocks, snow covered still, some sign of life. Further south, and here we are at Keflavik at 3. Circling down, wheels, approach, gliding in to the frozen runway. Eleven hours flying. A wonderful experience.”

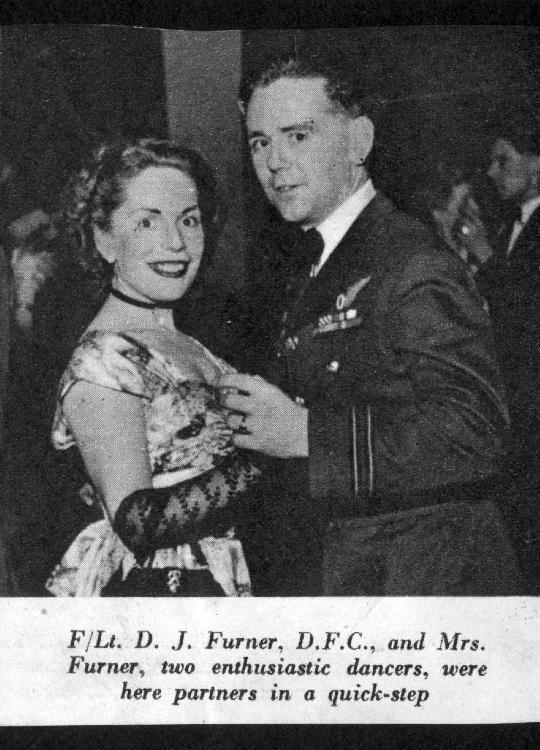

The course was very stimulating. Of the dozen on it, some of us are still around: Wg Cdr Gerry Daly in particular is a good and long-lasting friend. Such was No 9 Spec N Course which we completed in late March 1951. The end of the course coincided with the formal Annual Ball at Shawbury. The Tatler and Bystander attended and took pictures. Under the heading “Aerial Navigators Adapted their Art to the Ballroom Floor” they printed a lovely photograph of Pat, dancing with me, in their issue of March 21st 1951.

I had arrived at Shawbury eight months before without a Permanent Commission. Interestingly enough, I was the only one on the course without it. You can imagine my delight and relief when I received a piece of paper soon after the course had started which announced that my Permanency began on 1st October 1950. When I finished the course in top position, I thought to myself “Too right!”

I was to be posted to Boscombe Down for experimental work. I was still a Flt Lt (age 29). After that rather unhappy two years at Middleton St George, things might just be looking up—for Pat and for me.