The three weeks notice for moving the family to the USA concentrated the mind wonderfully. There were the inevitable final actions at Boscombe Down—ensure that all outstanding work was finished and that all responsibilities were fully and accurately handed over, brief my successor (Sqdn Ldr “Bunny” Hare), farewell parties—in addition to checking out the house, organising all necessary paperwork for travel and immigration into the States, and taking final leave in which to say au revoir to families.

So it was that on 27th November 1953 Pat, Peter and I found ourselves on a train to Liverpool where we would join our ship. We were fortunate on the train to have a compartment to ourselves and part way along the journey a very pleasant chap popped his head in to say hallo and introduce himself as “of the same service”—he was Air Vice-Marshal Geoffrey Tuttle, at that time Assistant Chief of Air Staff and on his way by the same means as us to a conference in Washington. (They don’t do it as leisurely as that these days!)

Our ship was the RMS “Media”, a single class ship which was very nicely fitted out. We sailed from Liverpool at 3 pm on Saturday 28th November (no, my memory is not that precise—they had a printing press on board and we still have some of its output). We had left rationed Britain behind and we were clearly in for a very pleasant week. Our cabin was most comfortable, the food was excellent, the passengers were friendly. On the Thursday evening 3rd December, in the middle of an Atlantic gale, we attended a Gala Dinner (we hadn’t seen a menu like it in our lives!); after which, Pat and I won a prize for dancing longest on one leg with a balloon between our foreheads, achieved, mark you, with a fair degree of roll in the gale. The AVM also won a prize that evening—a little sailor doll which he later gave to Peter as a keepsake.

On Sunday 6th December we disembarked in New York. I had returned after 11 years, but this time with my wife and son. We were immediately swept up into the arms of eager willing Movements staff who ensured that we were sent on our way to Washington where others put us into a hotel. The idea was that I should spend a day or two being briefed on USAF ways by the British Joint Services Mission before being sent on to Dayton. Travel to Dayton was again by train—overnight and all organised for us; at Dayton we were met by one of the dozen or so RAF officers stationed at Wright Air Development Center. It was well appreciated by the RAF contingent that each new arrival was so bewildered by everything that an escort who knew the ropes was essential for the first week. Our escort was Sqdn Ldr Derek Sanderson, and he was a tower of strength, helping to sort out many of our initial concerns and problems.

It was a culture shock, I suppose—that’s the way we would describe the situation today. We had left a comparatively poor country, still picking up the pieces after World War II, hampered by various forms of rationing, roads comparatively empty of traffic, certainly of new cars, working in a Service environment which, to say the least, permitted no extravagances, and individually all of us watching carefully every penny earned. We had arrived in the richest country in the world, comparative affluence evident in every sphere of life, new cars flooding out of the showrooms looking (slightly) different every single year, the growth of the supermarket concept already well under way, to work in the largest Air Force in the world, equipped with the greatest number of aircraft and aircraft types. In short, we had entered Aladdin’s cave.

Once we had put our kit into some temporary VOQ (Visiting Officers Quarters) on the base (our 8th address, pending something more permanent), Derek Sanderson said to me: “The first thing is this—you’ve got to get a car—you won’t cope without one. The 1953 models are now being discounted so let’s get choosing. The RAF here go for either Chevrolet or Studebaker.” We looked at both. The Chevvy was the cheapest of the General Motors line-up of makes. The Studebaker was futuristic with a bullet nose. We chose the Chevrolet. The 1954 model had about two pieces of trim different from the 1953, but as Sanderson had forecast, the few remaining 1953s were nicely discounted. How to pay? No problem. Small deposit, rest on HP over two years. The car cost the equivalent of £600 and the HP arrangement was no pain at all. We had arrived in Dayton on the 10th ; the car was ours (and the Finance Company’s) on the 11th. All signed and sealed, I drove away with a Chevrolet Bel Air two-tone coupe with a 4-litre engine; gear change up near the steering wheel; bench seats front and rear—room for six. Never had any new car before, let alone one like this!

Next—accommodation. In normal times, we gathered, we would have been offered the USAF equivalent of a Married Quarter. There was a large estate of them, detached houses, all elaborately furnished, described by the name “Wherry Housing”. Wherry, I understood, was the name of a Senator who must have had something to do with the concept. However, at the time of our arrival, there was a major dispute going on between the USAF and the local Gas company and in consequence there were no new movements inwards. So—no “marching in” for us this time. We had to seek outside in the town a rental which would be taken over by the USAF as a “hiring” in the same way that we had experienced in Amesbury. Anyway, the end result was our 9th address—3725 South Smithville Road, Dayton—a “duplex”, which means a semi-detached bungalow in our terms. And very nice it was too: an L-shaped lounge cum dining area, a kitchen, bathroom and two bedrooms, central heating by gas and fan-driven air through the floor, carport; kitchen equipment and beds supplied by the USAF stores people. We moved in on the 15th.

We had to purchase the rest of the furniture. Now remember this—we’re well into December 1953 and the mercury’s dropping like a stone. The temperature was getting down to a negative figure Fahrenheit. The roads were icy with crunchy snow tracks. I borrowed a trailer to hitch on to the Chevvy and we did a bit of judicious buying of everything we needed to set up the minimum of a home ready for Christmas—with a tree and a piano! More HP, spending money like there was no tomorrow. Ah yes, money—let’s talk about money for a moment. Some time before we arrived in the USA the rate had been $4 to the £, the same as during the war. But we were now in a different situation; the £ had weakened so markedly that the Government had devalued it to $2.80 to the £. The good news was that the Air Ministry, presumably with the agreement of the Treasury, had decided that, temporarily, exchange officers who happened to be in the USA at that time could continue to be paid in dollars at the previous rate; as you can readily see, that decision made quite a difference to us; the arrangement was to last through my tour. You win some.

We three were fully settled into No 3725 in time for Christmas and I was ready for work immediately after. Pat and I had to regard one more domestic problem as not yet solvable. Peter was now 5 and would normally have been attending school in the UK. The starting age in the States was 6. Pat therefore resolved to teach him at home: she had had a year of teaching experience (1947) in an Infants’ school in Norwich. She set for herself a disciplined programme for about three hours every morning from Monday to Friday, covering the three Rs, piano and bits of History and Geography. Except for trips away, she carried this programme right through the year 1954. At 6 years old he was welcomed into the local Infants’ School in late 1954. Needless to say, he had a head start on his contemporaries but there was no way the School authorities would bend the rules and move him up a Grade. During the rest of his time in the States, Peter was largely marking time. This was a worry.

Smithville Road was in a south-eastern suburb of Dayton. The city was large—population a quarter of a million, extending to more than half a million in a metropolitan area. It contained many industries, notably auto parts, machine tools, refrigerators, air conditioners, computers, accounting machines and magazine publishing. It had two Universities, a Museum of Natural History and a Philharmonic Orchestra. It was situated towards the southwestern corner of Ohio, a State bounded by Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, Kentucky to the south and Indiana to the west. It sat right on the confluence of three rivers—the Great Miami and two tributaries, Stillwater and Mad Valley. What with all those waterways and the Great Lakes to the North, the area was known locally as “sinus valley” and during that first winter we soon found out why. At one stage I had to have an operation on a nasal polyp (whatever that is).

The noteworthy point about the state of Ohio was that, although fairly well down the list in terms of total area and population, it had more large cities (say over 250,000) than most other states—Cincinatti, Toledo, Cleveland, Akron, Columbus and Dayton, all very busy places industrially.

Now to work. Wright Patterson Air Force Base was a vast organisation employing 28,000 personnel who drove into work every day in 27,000 cars. The rush hour was really something. The Base comprised two separate parts—Wright Field, named after the pioneers Wilbur and Orville Wright; and Patterson Field, named after John Patterson who founded the National Cash Register Company in Dayton. The two Fields were situated to the northeast of the city. Patterson was the larger, housing many thousands of civil servants who administered the procurement and logistics functions of the Air Force world-wide on behalf of Air Materiel Command (AMC). It was from Patterson that I was to do most of my flying because it had the longer runways, but my office work was at Wright Field, the home of Wright Air Development Center and part of the USAF’s Air Research and Development Command (ARDC), which comprised a number of Laboratories, each engaged in research and development of different groups of aviation equipments. I was employed initially in the Armament Laboratory, later renamed by a merger as the Weapons Guidance Laboratory, commanded by Colonel Larry Israel; I soon discovered that the Colonel was a Hi-Fi enthusiast for he entertained Pat and me one evening and demonstrated the largest speaker units I have ever seen in my life, then or since. There were other Laboratories—Power Plant, for instance, and Communications, in which most of the other RAF people were employed. Throughout the complex of WADC there were a dozen RAF exchange officers—one Group Captain (a delightful Engineer by the name of Max Perkins) and a mix of Wing Commanders and Squadron Leaders. I was the only flyer (General Duties) and the youngest; the rest were mostly Engineers and a few Admin types. My predecessor had also been a navigator but had been repatriated before I got there. I therefore had no kindred spirit with whom to discuss the work: the other eleven RAF hadn’t a clue as to my sphere of activity.

I soon learnt that the job was precisely what I was going to make it. The Americans, I’m sure, couldn’t have cared less whether I wished to play a useful part in the Laboratory or whether I was prepared to laze my way through the tour of two and a half years. The latter I could not do—the former it had to be. But it was up to me initially to seize my own tasks, which was a slow process. I suppose you could say that I gradually wormed my way into this and that, building up my own expertise on their systems, so that in due course I could express sensible views, could write knowledgeably and to good effect on some of their problems and could assume flight trials on my own without their backup. That last was the welcome proof that I was being of use to them. Slowly but surely I became one of them. My slight American accent developed. (I quickly learnt, for instance, that to pronounce Furner in the English way would be taken as Foehne, hence it developed in speech to Furrrr-nerrrr.)

Within the Weapons Guidance Lab, I was assigned specifically to the Strategic Bombing Branch. A very impressive officer—Colonel Norman Pershing Hays—was the Branch Chief; he was unusual in being an Air Force navigator—the USAF was perhaps not as enlightened as the RAF in the matter of navigators’ promotion. Under him was Lt Col Perry Bryant, an Engineer, who was an extraordinary mix of brilliance and scruffiness. His place was taken later by Major Bob Duffy, known to his colleagues simply as “Duff”; it was with him that my closest friendship grew over the time I was there. He is now a retired Brigadier and we still keep in touch; he even hosted our third son many years later. It was he, in a spirit of bonhomie, who shortened the awkward ‘Squadron Leader’ to ‘Squalid’. And there were Captains Charlie Minor and Bill McKenna, both pilots, again both in touch. There were civilians too: Tom Pienkowski I remember, he was a very keen classical music lover and eager to own the latest in Hi-Fi; and Dr Karl Kober, the resident German, a sort of parody of Dr Strangelove, but we got on fine; and “Doc” Burka who, running in the rain, would try to work out mathematically whether he was hitting more raindrops by running than by walking slowly, and who demonstrated to Pat and me his boundless library of bawdy songs on tape; and George Fouse who organised the most marvellous New Year’s Eve parties in his basement (most houses had a basement, but not our Duplex); Elmer Wieland whose marriage broke up; and the delightful Lou Muhleman, an older man, and quiet, with whom we continued a friendship until his death.

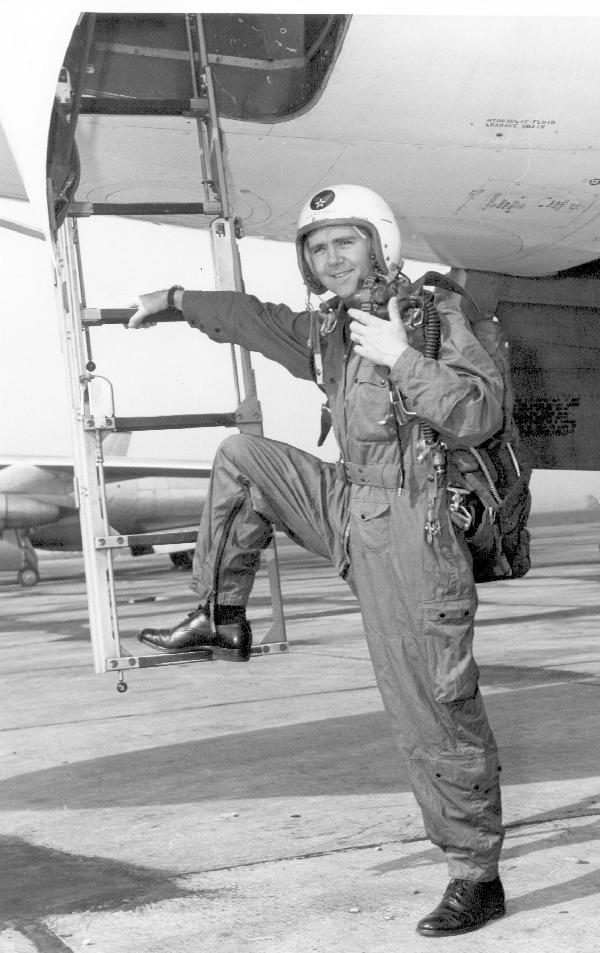

During my time at WADC I flew in several types of aircraft—the WWII B25, B26 and B29 (remarkably, exactly the same B29 I had flown at Boscombe Down—my markings were still there in the astrodome); the newer B36 (10 engines, “6 turnin’ and 4 burnin’”), the 6-jet B47 and the 8-jet B52 (astonishing that the B52 has been still operational in 1999 against Milosevic of Serbia); and the T29 and T33. I flew with 41 USAF pilots. The aircraft flown most was the B47 which had recently entered service with Strategic Air Command (SAC) and was thus the backbone of the US nuclear deterrent force; a total of 1,600 B47s were built. I tested modifications to its nav/bombing system known as the “K” system; did trials on the K system in different modes; ran trials on CRTs of differing diameters (they started with 5 inch scopes—we in our V-Force went straight for 10 inch); undertook some radar photography; carried out compass calibrations; tested the US version of Doppler as connected to the K system; ran trials on some Electronic Countermeasure equipment and on map-matching; navigated Maj Gen Boyd, chief of WADC, to Edwards Air Force Base out in the west which later became famous for the shuttle landings; accompanied a number of my pilot colleagues who had to fly in the T type aircraft in order to keep their flying hours going; and finally kept surveillance on an initial flight of a prototype inertial equipment. I remember towards the end of my time mentioning that there were still 3 of the then 48 States which I hadn’t flown over. They made sure that the route chosen for my last test flight encompassed those three States.

Every now and again there would be meetings at the site of one aerospace company or another, for instance to Boeing in Seattle, Sperry in New York, IBM in Endicott, Convair in Fort Worth; and with academia, for instance MIT to meet the “father” of inertial navigation, Doctor Charles Stark Draper; to St Louis for a mapping conference, to Norfolk Virginia for coordination with the US Navy; to the Pentagon for a broad sweep of Strategic Air Command’s concerns; and to other USAF Bases, for instance, Patrick AFB (later renamed Cape Canaveral and co-sited with Kennedy Space Center); Eglin AFB on the Florida coast of the Gulf of Mexico; and Mather AFB near Sacramento in California to do a course on the K System fitted in the B47.

I have fond memories of some of those visits. I took a commercial flight to Seattle and the aircraft circled, in glorious weather, the snow-capped summit of Mount Rainier at 14,000 feet. The two visits to the Sperry Gyroscope company were long ones—at least a month—not only to attend meetings on their inertial prototype (called TEMPO) but to undergo a short course on the equipment and to receive an appraisal of my efforts on the course; in true American style they assessed my overall performance as 99.9%. I particularly liked the .9! On both occasions, in view of the length, Pat and Peter travelled with me and we rented accommodation on Long Island—more on that later. IBM’s Headquarters at Endicott, New York, was memorable in that the Staff Club housed the only Juke Box I’ve ever seen filled with 12 inch LPs of classical music. The visit to Fort Worth was exhilarating. Convair seemed to have built the longest hangar I had ever seen in my life. In one end poured masses of raw materials and spare parts; out of the other 10-engined B36s taxied out to the runway.

As to MIT’s “Doc” Draper, a name revered in the theory of inertial navigation, it was he, I recall, who interrupted a briefing he was giving us in his office one afternoon, looked at his wall clock, observed 5.00 pm, touched a button under his desk, moved the clock round one hour, and served drinks; a very polished performance which I suspect was one of his little ways to set his colleagues at their ease. He was the Chairman of the Aeronautical Department at MIT and had already achieved fame for his work on gyroscopes installed in airborne bombsights and naval gunsights. The purpose of the meeting I attended, with others from Wright, was to explore the possibilities of his further work on a new navigation system for aircraft called Spatial Inertial Reference Equipment (SPIRE). His later work was concerned with the miniaturisation of such equipment and its role in the future guided missiles like Polaris and in the Apollo project which within another 15 years would land Americans on the moon.

Having mentioned MIT I recall the story of the eminent prize-giver at Yale who decided to base his speech on the four letters of the University and thus spoke on Youth, Ambition, Leadership and Excellence. He was very long-winded and went on and on with all four subjects. As he was just about to start on Excellence, one of the Faculty behind him whispered to his neighbour “Thank God we aren’t the Massachusetts Institute of Technology!”

I have referred a number of times to “inertial” navigation. What I was experiencing was the start of a vitally important new development in navigation. I had seen nothing of this at Boscombe Down because there was no such equipment yet in the UK inventory, although the theory was being studied elsewhere within the Ministry of Supply. Here, in the US, there was massive effort in exploiting the theory in order to produce a practical aid for future navigators. In essence, this is what inertial was about: the use of super-accurate gyros set in three-dimensional gymbals and the electronic double integration of their reaction to acceleration. First integration of acceleration gives a measure of velocity, second integration gives displacement or distance. Given a start point in X,Y coordinates, apply the distance in the same coordinates and you have present position. The coordinates could be northing and easting, along and across track, or polar, or whatever, and be updated only infrequently by other fixing aids, thus ensuring electronic silence as much as possible. Of course the prototypes were unwieldy and inaccurate. First models were hung in 5-foot diameter outer gymbals—enormous dinosaurs—and were subject to precession and other errors. All major companies were making them, I worked with just two of them—the two I’ve already mentioned, SPIRE and Tempo. The construction of the gyros and the associated electronics demanded the most rigorous attention to accuracy standards and ambient conditions, dust-free and all that, employees in immaculate whites. So these were the early days; the years that followed saw progressive improvements in manufacture, in reliability, in techniques, to the extent that today’s military and commercial aircraft and most military missile hardware are fitted with super-accurate and highly miniaturised inertial equipments.

For the last word on work during my American tour, I record that the main difference between the US way and the British way in these matters was concerned with scale of effort. Whereas TRE or RAE in the UK would have the resources only to come up with one feasible answer to a problem and go for it, our transatlantic cousins would extravagantly feed out all possible methods of solving a problem to company after company and task them to come up with varied solutions from which the right one would be chosen. Very expensive but very effective in the long run. [Having said that, we in the UK were equally extravagant in attempting to solve the question of which post-war medium jet bomber we should go for in the V-Force, but more on that later.]

So much for work—all very exhilarating, intriguing and not to be missed by an enthusiastic navigator. Possibly the most encouraging aspect of working with USAF was that, despite our inevitably smaller size, respect was mutual. I was destined to appreciate that fact even more in later postings. Now I turn to the social and domestic side of our time in the States.

We had some quite wonderful times during our two and a half years in the USA. Perhaps if I had to choose one particular happening to describe in detail it would have to be the occasion when I was sent on the radar course at Mather AFB that I mentioned above. It was arranged for me in May 1954. I asked if I could add leave, like three weeks, so that we can see more of your country? “Sure, go ahead” was the answer. Not much time for preparation—pore over maps, check on probable stopping points, check the car, buy a camera and reels of colour slide film, pack. And one brilliant sunny morning on the 2nd of May the three of us locked up No 3725, filled the trunk (boot) of the Chevy, checked everything checkable under the hood (bonnet), and we were off—on a 7,000 mile journey, and since most of the distance westwards directed us to Mather, I was paid so much a mile for a large majority of that 7,000 by the USAF. What followed was quite superb. In those days, 45 and more years ago, tourists from other countries were rare indeed; and May was not at all a crowded month for the highways we were to travel on and the national parks we planned to visit.

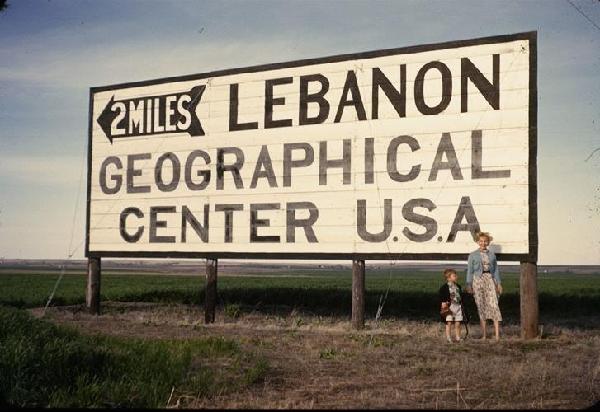

We made straight for Indianapolis and Springfield, in Illinois, where Abraham Lincoln lived for many years. We crossed the mighty Mississipi and stopped for the night in a Motel at Hannibal, famed for its own Mark Twain. All our night stops were to be in Motels—very convenient. We filled up with gas (petrol) every morning at about 20c a US gallon but settled with a Gas Credit Card—my first experience of such a thing; the bills took months to find their way back to Dayton. The next morning we drove on through the rolling country of Missouri into Kansas, with dead straight roads, flat farmlands and isolated communities. At a tiny spot called Lebanon stood a stone monument indicating the geographical centre of the United States. (Easy to reckon then—Alaska and Hawaii were not yet States.) There was nothing but wheatlands and sky, maybe a farmhouse every 20 miles. New York and Washington were remote indeed, let alone Europe; it made isolationism comprehensible.

We stopped the second night at Phillipsburg. By noon on the third day we could see the terrain to the west changing markedly; we were approaching the Rockies. We were in Colorado and there was the large city of Denver. We aimed out of the city by toll road to a smaller place called Boulder City, lying in the foothills at 5,000 feet; we booked into a Cottage Motel and walked in the clear sweet air. The fourth day was magical. At 7 in the morning we started our ascent into the Rocky mountains. We ate breakfast in a tiny town called Nederland. The weather was perfect: crisp, sunny and clear. The roads twisted and turned, snow glistened on the peaks and over all there wafted the most lovely pine scent from the trees that covered the slopes. We gradually climbed to a height of 11,300 feet to Berthoud Pass straddling the Continental Divide. Here there were sheer drops and precipitous descents; but the roads were a remarkable feat of engineering, graded so skillfully that we could drive in top gear practically the whole journey. At the Pass we stopped for photographs, a souvenir and a drink, and began a descent and a second ascent to Rabbit Ears Pass at 9,700 feet, where we had a spectacular view of the valley of the River Yampa thousands of feet below. We continued on through many miles of rugged barren plateaux, rocks and scrubland and canyons, seeing the odd shack some 60 miles apart; and crossed into the wonderful State of Utah, the “promised” land of the Mormon pioneers, stopping for the night at Vernal.

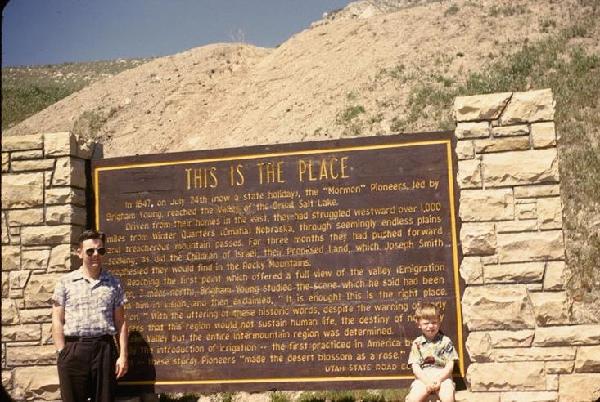

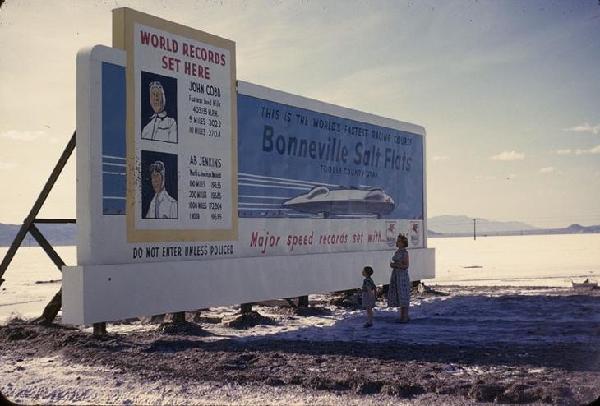

The next day was fine and hot. We were soon in the midst of the most varied scenery yet. We were surrounded by snowcapped mountains, lakes—one with the luscious name of Strawberry—bright green fields, through Heber City, then down a winding canyon past Brigham Young’s “This is the Place” monument to our first sight of Salt Lake City. What a vista!—the City with its Capitol building and its Temple prominent, partly ringed with mountains, and the salt lake to the northwest. We drove down clean tree—and flower-filled boulevards, no advertising to be seen, and stopped to visit the Temple Square, where the gold figure of Brigham Young topped the Temple and where we could hear the organ practising in the Tabernacle. We saw the Seagull Monument which marked the extraordinary event of the seagulls, 700 miles from the Pacific, rescuing the Mormon crops from a plague of locusts. Then we were back on the road heading ever further westwards, past the Great Salt Lake with its salt content nine times that of the ocean, and on to a 40 mile stretch completely straight and flat where you could sense the curvature of the earth, past the salt desert, stopping briefly at the huge signs announcing the Bonneville Salt Flats and all the landspeed records up to that time. The names of Malcolm Campbell and John Cobb were prominent. Soon, at Wendover, we were crossing into the State with a contrasting reputation to that of Utah—Nevada. Straight-laced Utah gave way to loose-living Nevada. We stopped that night in Wells.

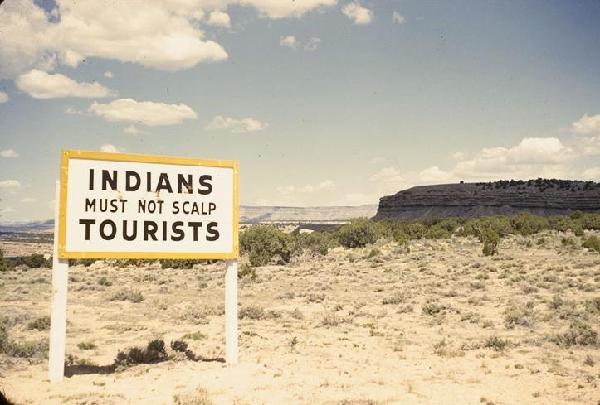

Day 6 was a Nevada day. We had a straight fast run through desert and dried up salt lakes, sagebrush and mountains, with unlimited visibility on a fine, warm day. The State demonstrated its sense of humour with roadsigns—“ Sagebrush is free; stuff some in your trunk.” -—“ Indians must not scalp tourists.” We stopped at Elko where Bing Crosby enjoyed 18,000 acres of land and 4,500 head of cattle, passed Battle Mountain, Winnemucca and on to Reno (“The Biggest Little City in the World”) We stayed the night in Reno and found it gaudy and tinselly, with most of the population frenetically pulling machine handles, especially in Harold’s Club which claimed an average of 5,000 visitors per day.

Day 7 of our travels (Saturday 8th May) was very warm and sunny. We passed through Carson City, named after Kit Carson, through Virginia City, a ghost town, and then climbed into the Sierra Nevada and circled, very slowly, the beautiful Lake Tahoe. We have never forgotten that Lake—turquoise and deep blue waters, sands, pines, mountains, snowcaps—one of the loveliest sights we ever saw. We watched reflections of trees and mountain tremble in the water. We ate lunch on the sandy shore; Peter was happy rolling a log in and out of the water. In a little shop where we bought him a Viewmaster was hanging a picture of our Queen. Around the lake we had crossed into California: the boundary between the States split the lake. We made the long descent through the western Sierra, following rushing streams and pineclad slopes, from 7,000 feet to sea level. It was the first time we had been below 5,000 feet over a period of five days. We drove past Mather AFB to lodge for the next week at the self-catering Tahsoe Acres Motel in a small town called Perkins. I then spent the week at Mather, as I’ve already mentioned, completing a course of instruction on the “K” system—the nav/bombing system in the B47. During the week we enjoyed the sights and sounds of Sacramento, the capital city of California which was nearby.

A week later, on Saturday 15th May, we drove to Cordelia, thence to Napa and by winding English-type country lanes to the coast at Stimson Beach. Here, with our first sight of the Pacific, we had a picnic lunch; the sea was too cold for a swim. We turned south along the coast and crossed the Golden Gate Bridge into San Francisco—a very impressive entry. We booked into the Marina Motel and cruised around to explore the City. The traffic was light: we saw the Golden Gate Park with its Japanese tea garden, rhododendrons, deer and bison; Ocean Drive, the waves, the beach; white buildings, cable cars, Chinatown with its lanterns, curios and tinkling music; Alcatraz; the up and down roads and how you must take care with parking—an offence not to turn the wheels into the kerb.

The following morning we left San Francisco in thick fog. The fog lifted quickly as we turned inland, through rich fruit growing areas (peach and orange) to Merced, and on to our destination, Yosemite. We entered Yosemite Valley, through which the River Merced runs, with towering rock cliffs and high waterfalls all around us. “El Capitan” rock rose vertically 4000 feet above the river bed. Opposite it, the Bridal Veil Falls were flowing fast, May bringing down the winter’s snow. The Yosemite Falls in two stages, the Half Dome, Mirror Lake, we marvelled at them all. We left the valley to climb to a high observation at Glacier Point, some 8,000 feet up; there we had a magnificent view of the whole panorama with the Sierra in the background to the East. The final twisting descent, in gathering twilight, passed through the giant sequoias of Mariposa Grove; the “Grizzly Giant” was said to be 3,800 years old, 290 feet high and of 38 feet girth. Much lower down and out of the Park we stopped the night at a Motel in Okehurst.

Early 17th May saw us heading west again, back towards the Pacific coast; to Coarsegold we drove, to Chowchilla, Los Banos, Hollister and Castroville, through fertile valleys, fruits and flowers and artichokes. On the coast the weather changed. The comparatively cool ocean provided mist and low stratus. We strolled around Pacific Grove and Monterey, and drove along the “17 mile drive”, almost on our own all the time, observing cypress trees, seals, sand, rocks and wild flowers in profusion; and thence to Carmel, which we liked immediately, clean, no signs, homes of artists and writers, quaint shops. We left Carmel on the coast road State 1, a beautiful coastline, winding road, many islands with seals, completing the day’s travels at Big Sur, where we stayed overnight at Redwood Cabins. For once, the food was quite disgusting.

We left Big Sur the next morning in thick fog and remained on the coast road until Morro Bay where we took a walk on golden sands, then travelled inland for a bit to San Luis Obispo (most of the names are Spanish along the South Californian coast) and saw the 1772 Mission there; and with the temperature rising and the mist dispersing, on past lemon groves to Santa Barbara, a delightful town with largely one-storey buildings, many palms and flowers and a 1786 Mission. We stopped in Santa Barbara at the Travellers’ Motel.

From Santa Barbara on the 19th I can’t recall now how exactly we had planned the day but I think we must have changed the plan as the day progressed. It went like this. The coast road was now swift: it was US 101 in those days. Let my notes taken at the time record what happened.

“Malibu Beach—well! Chalkwell better. Will Rogers Beach—same. Then turned into the maelstrom. Santa Monica corny, the used car corner of the world. Warmer and sunny now but smog! Ugh! Thru’ miles of mediocrity—west Los Angeles, Beverley Hills (vista of a few pleasant streets). Hollywood—corn. To Hollywood Bowl, interesting. Past Universal Studios, Warners, Disney, NBC, CBS, Columbia, Paramount, Chinese Theater, thru’ Griffith Park, twisting roads, nothing to see (smog), past Planetarium, then down Vermont Avenue to join US 66—whoosh. Scuttle out like scared rabbits, fleeting glimpse of downtown LA (City Hall) then out at 50 mph to Pasadena. Straight East, past Santa Anita racecourse, thru’ orange groves, grapevines and petrol stations to San Bernadino—smog all the way. Up up up to 7,000 feet, along the Rim of the World drive to clear air.”

So you see, whatever we had planned to do and see in that great metropolis with the lovely name Los Angeles, it didn’t quite work out. Up in the clear air at height we pressed on to Big Bear Lake where we stayed in a cabin alongside the lake and, once we’d disposed of a hundred or so ants, liked it so much we stayed for two nights and on the full day there, got a lot of fresh air and exercise walking and boating.

Friday 21st May started sunny, hot and windy. After negotiating the twisting roads getting down from the mountains, we sped across desert and scrub, through Lucerne Valley and Victorville, and on to Barstow and Baker (temperature 92 F), soon to quit California for the first time in 13 days and cross into Nevada once more. Acting on advice on this day we filled a large canvas bag with water and tied it to the front of the Chevy—the water kept cool in the airflow. Facilities in those days in the Mojave Desert—cafes, garages—were few and far between, and I wouldn’t have liked to have had an emergency stop. Finally we drove into “the strip”—just about one main road then—of Las Vegas (The Meadows!): gaudy hotels and motels, gambling joints and cafes. A motel marked outside as 5 to 6 dollars asked for 15; it was a Friday. We hadn’t the funds for that sort of profiteering. After driving past the Golden Nugget and the Pioneer Club, we exited quickly and moved on to Boulder City, so different from Vegas, planned layout, green, clean, no hoardings, mainly housing the administrators and engineers of the Hoover Dam which had been built between 1930 and 1936. We liked it there. We stayed at the Vale Motel run by some very welcoming Germans. We went on a conducted tour of the dam—the power house, pipes, the generators, the pylons—and surveyed the lake so formed, Lake Mead, at that time 100 miles long. The vast wattage produced by the enterprise just about keeps the lights of Las Vegas going to this day.

The next morning we headed back to Las Vegas and drove out to the northeast to cross into Arizona at Mesquite. On this occasion, we were in Arizona only for a few miles of its northwestern corner. The road soon entered the state of Utah and we were twisting and pitching at about 5,000 feet. The red mountain scenery was spectacular; there were other colours in strata and the effect was prehistoric. After St George we left the main highway to approach the Zion National Park. The scene was reminiscent of Yosemite: we entered the river valley at 4,000 feet and had towering above us gigantic rock masses to 7,000 feet. The roads on the valley were designed for car observation: we drove slowly, stopping here and there, at the Weeping Rock, the Great White Throne, the rock Temples; and we departed through a climbing tunnel with lookout points through which the valley below could be seen every 200 yards or so. Out into the open, the terrain was weird—that’s the only word; mesas, eroded by wind, looking so much like giant wedding cakes. But slowly, a gradual change to flat plateau (still at about 6,000 feet, green with grass, pines, cattle and red sand; we were approaching Kanab, the home of some film westerns. We stayed in Kanab at a motel called just that. Nearby were a couple of wigwams marked “Squaws” and “Braves”.

Sunday 23rd May dawned fine and warm; the visibility seemed unlimited. This was an important day. We crossed back into Arizona; border officials insisted on an inspection of any cacti we might be bringing in. We had a fast run through the Kaibab National Forest, then for some distance we were paralleling the Colorado River with the Vermillion Cliffs on our left until we reached Marble Canyon. There we crossed the Colorado by the Navajo Bridge and looked down upon slow running muddy waters only 500 feet below us. What a contrast there was to be very shortly. Having crossed the river, we reversed track and sped along the Echo Cliffs reflecting the Vermillion, seeing no sign of civilisation for some 70 miles. Soon we were inside the Navajo Indian Reservation, seeing from time to time Indian mudhuts and small settlements. We turned due west at Cameron and climbed to 8,000 feet; the terrain was utterly flat at that height. Then you see for the first time what must be the world’s most extraordinary geological sight: the Grand Canyon. Discovered first by Spanish troops who had no conception of heights or distances (they estimated the Colorado’s width as a couple of metres), that first sight is guaranteed to take your breath away. The Canyon as a whole is 200 miles long—it would span the whole width of England—and is a mile deep, with the bed of the river down at 3,000 feet, and varies in width at the top, averaging about 10 miles. For millions of years the river has been deepening its course through this stretch of Arizona and until 18 years before would have had an uninterrupted journey to the Pacific. Now it is temporarily blocked by the Hoover Dam and soon after that it flows under an unusual interloper, the old London Bridge, at Havasu City.

We drove along the south rim as far as tarmac roads would allow and stopped at all of many observation points from Desert View in the east to Hopi Point in the west. Between the north and south rims were hundreds of rock castles, the slope of their sides determined by their vulnerability to erosion, fantastic columns, individual tributary canyons, a mule trail to the bottom, and at the bottom, a mile below, the Colorado River, sometime slow moving, other times white water, fast and dangerous, depending on the angle of slope; with one suspension bridge for athletic walkers, having experienced five climate bands on the way down, to climb up to the North Rim. We found it difficult to leave this wonderful sight. But leave we must. We travelled south from the Canyon, observing the mountains known as San Francisco Peaks from a distance of 70 miles. We drove fast at a constant height of 7,000 feet to Flagstaff, passing the Wupatki National Monument, Sunset Crater and the snowclad peaks at 12,000 feet, Arizona’s highest point. Then we were back on US 66 turning east and passing Meteor Crater. We stayed the night in the small town of Wimslow, largely populated by Indians.

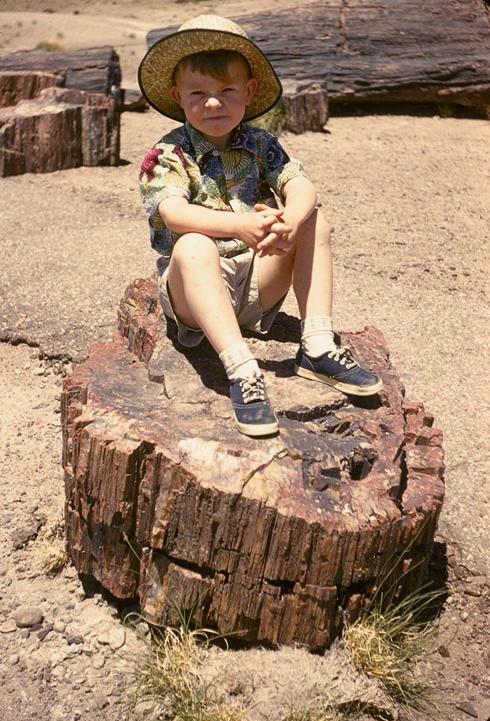

The next day was the start of a fast run home to Ohio—which would take four days. But early that morning we had one more planned sight to see—the Petrified Forest, consisting of tree trunks which for millions of years had lain in swamps and were now scattered over a desert floor as pieces of stone, of quartz. We were alone wandering around the large area of petrified pieces, occasionally here and there seeing early Indian hieroglyphics inscribed. Nearby was the Painted Desert, so called because of banded streaks of differing colours in the desert rocks. Then it was time to go—stopping that night at Albuquerque, New Mexico, at the southern end of the Rockies; next day into Texas and on to Oklahoma, stopping at Yukon, just short of Oklahoma City; the following day through Tulsa to Sullivan, Missouri, 65 miles west of St Louis; and finally, on Thursday 27th May, after a brief visit to the Meramec caverns, we aimed for Indianapolis (we had now come full circle) and thence to Dayton. We had started our travels on 2nd May with the mileometer reading 5,000; we had returned on the 27th with a reading of 12,000.

I know that I’ve spent a lot of time and words describing that month of May 1954. Today, at the end of the Century, that form of travel is simple and easily planned—and Pat and I have been back a number of times since to relive the experience. But you must understand that in 1954, long before tourism took off, it was a momentous undertaking and a memorable experience—one we have never forgotten.

Almost immediately after returning to Dayton, there was good news: I had been awarded the Air Force Cross in the Queen’s Birthday Honours for my work at Boscombe Down.

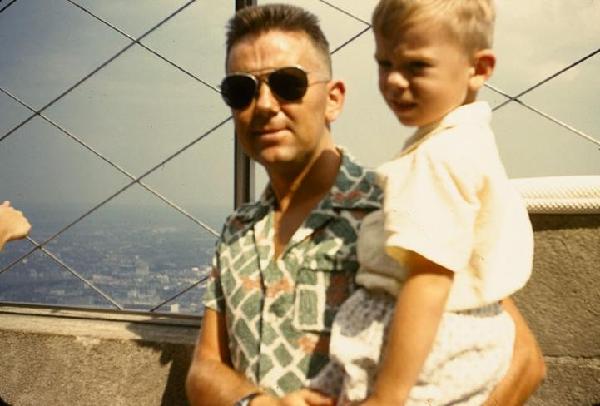

There was much more travelling. I’ve already listed some of the commercial air travel in connection with work. There were also occasions when we drove and Pat and Peter came with me. For instance there were two sessions in the New York area, both to work with the Sperry Gyroscope Company on TEMPO. The first period was for a month: we headed east from Dayton, using the new Pennsylvania Turnpike for much of the journey, and finished up in a 10th (temporary) home at 134 Franklin Street, Long Island, NY. Our landlord was Mr William Scherer, a guard at Sperry’s. The pattern of work demanded that I leave Pat and Peter for a week, flying with Sperry personnel to Atlanta, Birmingham and Pensacola, and return; on one of my phone calls back to Long Island I was dismayed to hear that Peter had chickenpox and was house-bound. Nevertheless, we still found time during the month to “do” New York as much as possible, on this occasion, Empire State, 5th Avenue, Lindy’s, Times Square, Coney Island, Long Beach, get lost in Brooklyn, carry home 2 stones of Sunday papers, spiral 22 floors to look out from the head of Liberty; (“Lived here 50 years and never seen it”, said Mr Scherer); the enchanting play “Ondine” with Audrey Hepburn and Mel Ferrer, and Barnum and Bailey & Ringling Circus at Madison Square Garden—tremendous. We returned from that trip via the “Finger Lakes” in north New York State, Niagara, Erie and Willoughby; thus clocking up another 1000 miles and the complete width of the USA.

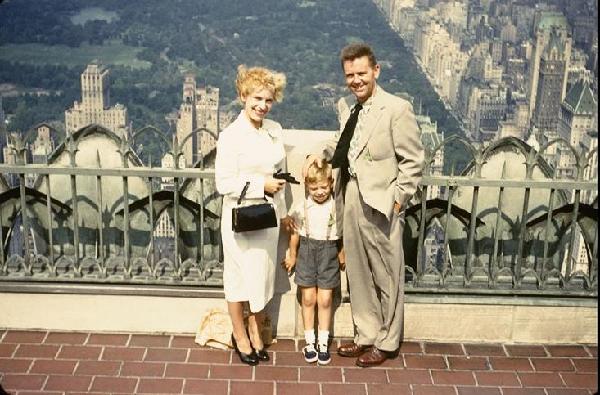

The second visit to New York was longer—two months. This was the one which included the 99.9% course. So we settled into our 11th home at 18748 Jordan, St Albans, Long Island, some apartments run by Mae Mooney; it already housed a couple, Mavis and Bolling Robertson, with whom we were to become firm and lasting friends. We made sure during this visit that we saw everything else in NY: took a tour around the United Nations Building, attended the Hayden Planetarium, sped to the top of the RCA Building—by day and by night—investigated the Theater district, saw “Kismet” with its beautiful Borodin music, and “Brigadoon” and “Teahouse of the August Moon” and “No Time for Sergeants” and “Can-Can” and the stage show at Radio City Music Hall; and drove through every tunnel, over every bridge and along every parkway, and got lost in Brooklyn.

We also made separate trips by car to Akron, Ohio, and to Cincinnati; to Hamilton, Ontario to see the Buchanans whom we had known at Middleton and Boscombe; and to Virginia to visit the Robertsons who had moved from New York.

There was another very important element of the job at Dayton—entertaining. We were expected to entertain our US colleagues and to this end we were supplied by Washington with a drinks account, and by a beneficent Treasury at home with an Entertainment Allowance. We discovered early on that some of the other RAF types there were entertaining mainly among themselves, which to my mind was not the main aim. Fine, in moderation, but concentrate on the Americans; so we socialised as best we could with all our American friends and of course they entertained us back. There was thus a real social whirl. I learnt that the favourite cocktail of my colleagues was the Martini; I used to put the gin in the freezer for a time, and when the event started, it poured like oil; add 1 part French vermouth to 4 parts very cold gin, add the olive and the place would be jumping in no time at all. (To the question—“should the olive be eaten with the fingers?”—answer “No, the fingers can be eaten separately.”) Anyway, suffice to say that there was a lot of it going on, and one had to be young (yes) and fit (try to be) to keep up with it. I recall one dreaded afternoon picnic session on a 4th of July—and you know the significance of that date, particularly as it applies to Brits—when my drinks were spiked and I hardly knew how to drive home. It was all in the best of spirits, of course.

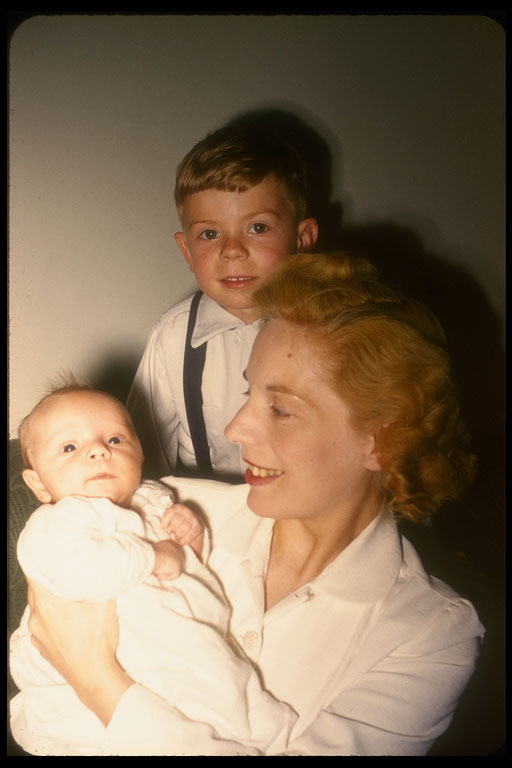

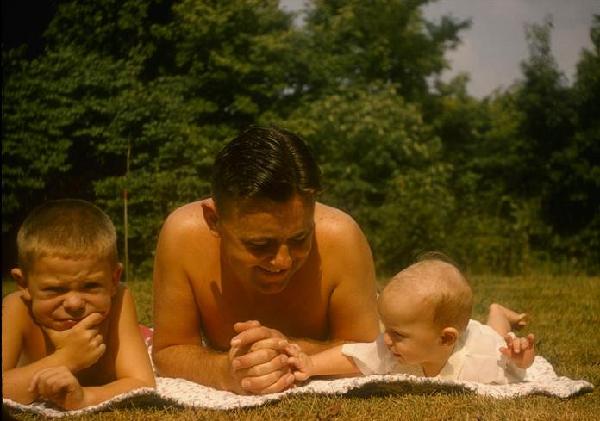

Through all of this, Pat was her charming self—always the gracious hostess, always looking her best; she was known among USAF colleagues as the English Marilyn Monroe. At the same time, mark you, she was keeping Peter up to scratch on his initial education ( he started infants in late 1954 when he reached 6) and by March 1955 had given birth in the USAF Hospital to our second son, Richard. Many years later, we were to hand over to Richard a fistful of birth certificates—US, USAF, RAF and British Embassy—and he enjoyed dual citizenship until he opted for British. That summer I remember a delightful fortnight when the four of us were invited to a country home on top of a hill by Lou and Mary Muhleman to look after the place and their big old Pyrenean mountain dog while they were away on holiday. Lou was a civilian colleague in the Laboratory; I was still at work and returned to the house and Pat and the boys in the evenings. It was unusual in this affluent and organised society to be operating the Muhleman’s own private well for water.

There was on the Base a speaking organisation known as the “Toastmasters”. The aim was to encourage public speaking by each of us talking on a subject of our own choice and then having it criticised by the others in the circle. I was welcomed to it and gave a number of short talks; my titles were “Over to Metric”; “Why Worry?”; “Impressions of the Southwest”; and “My Country”. Then there was a competition, going through various stages and districts—no choice, one was given a subject. I competed with “Radio and TV Comics”; then in the next heat with “Why Men wear Pants” (!); then finally representing the area (!) at a higher level in Columbus “The Art of Courting” . Great fun. Talking of radio and TV comics, we had TV of course—black and white then, and was always most impressed with a bunch of very talented US comedians: there was Milton Berle, Sid Caesar and Jackie Gleason—all excellent. We used to look forward, also, to Ed Sullivan’s Sunday Night show—very similar to Sunday Night at the Palladium back home. On a much more serious note, for a long period there was riveting TV produced by the witch-hunting Un-American Activities Committee chaired by Senator McCarthy. The doings were known as The McCarthy Hearings. Peter complained that he was losing children’s TV time because of the Carthy M’Hearings. By the way, Peter had a moment of fame when he appeared on a Dayton TV show with a bunch of other children around him.

Long playing records were taking a not insignificant proportion of one’s earnings—they were still monaural then; apart from the more serious side of music, we took a great liking to the amoral songs of Tom Lehrer, the Harvard Mathematics Professor, who had a nifty talent for good rhymes and catchy tunes. Later, we preceded his fame into the UK.

One more aspect of the social scene was introduced by visiting courses from the UK. One time the Specialist Nav lot came through, on another the Flying College Course; the latter was led by Air Commodore Gus Walker (remember the Group Captain at North Luffenham?), now one-armed; he lost one trying to save a pilot from a burning aircraft. It fell to me to brief these groups on what we were all doing at Wright Field. I rather think that Gus took special note of my activities and the aircraft types I was flying by what happened some time after we got back to the UK. More on that later, but the point here is that we had the groups at home for cocktails and canapes. On one of those occasions, a lady living a few doors down the road popped in: she had seen all the people and heard all the noise and wondered if she could join in. Later we discovered that one of the visiting team had taken the lady back to her home and was late appearing the next morning. She it was, too, who invited Peter in for a cookie and Coke one afternoon: Peter reported later that there were men there with her and they were all playing cards.

I’ve been going on for a long time about the American tour—it was a hectic time for both of us—both at work and socially. I could elaborate on more events in both spheres but I think I’ve said enough to give you an idea of what it was like. I should now draw this Chapter to a close. I was informed by Washington at the end of 1955 that I would be going home in June 1956 (i.e. after two and a half years) and that I would be replaced by another Sqdn Ldr navigator called Charles Ness. In my last Confidential Report, in the space allotted to “Choice of Next Posting” I had opted hopefully for the Flying College Course at RAF Manby, a mid-career course for GD Gp Capts, Wg Cdrs and a few Sqdn Ldrs. Well before the due date I learnt that that was what I should do next. In the final countdown to June 1956, the social thing became hysterical, there’s no other word for it. In our last 30 days, Pat and I were invited out every evening. Our baby-sitting bill was horrendous. There was one occasion I remember, a dinner party, where I literally fell asleep over the soup and had to be helped up the stairs to rest a bit. But apart from that one incident, we coped. Pat was done the farewell honours with a “shower” involving all the wives of colleagues. There was the final farewell from us to all of them; we drove to New York with all the necessary papers to embark; a dozen of the Lab people also turned up in New York; we thus spent the entire last night touring round Manhattan, an American bar, an English bar, an Italian bar, a German bar, etc, until we were quite dizzy with it and were literally poured on to the boat. (Peter and Richard were safe in a hotel room.) The journey home on the Queen Elizabeth was a most marvellous rest period.

We drove off the QE at Southampton in the Chevy, which although comparatively inexpensive seemed to look rather more opulent than the cars around us. It was noticeable to us that there was much more traffic, that towns were very close together, and that everywhere was green, so green after the parched US scene. After disembarkation leave spent with the two families, the four of us made our way north to RAF Manby and busied ourselves finding somewhere to live. We settled for a hiring (our 12th home) at 3 Cromer Avenue, Sutton-on-Sea, Lincs, only a short walk from the seafront. Since it was now July 1956, you’d have thought we were due for at least a couple of nice warm months. It was not to be. The summer of 1956 must go down in our memories as probably the worst summer we have ever seen—cold, wet and totally unsuitable for lounging on Sutton sands. A pity for the family; still, we entered Peter for the local school for just one term (and he did very well).

For me, it was back to a classroom for 5 months.