I must have been conceived in the middle of February. It would therefore have been fairly obvious that my mother was carrying me when she married the following August. Today, at the turn of this century and millennium, you would say—so what? it happens all the time.

But this was 1921 and there must have been quite a stir. If you mix in the following additional ingredients—that Grandfather William Paine Furner (groom’s father) was alive but not there, presumed dead; that Grandfather George Potter (bride’s father), metaphorically at least, was carrying a shot-gun; and that Grandmother Jessie Elizabeth (groom’s mother), who could not have been legally married to Grandfather William Paine at the time, was pretty snooty about the match and had been decidedly discouraging—then you can sense, even at this distance, that the event might have been a trifle fraught.

But we need to go further back in time to explain all this.

***

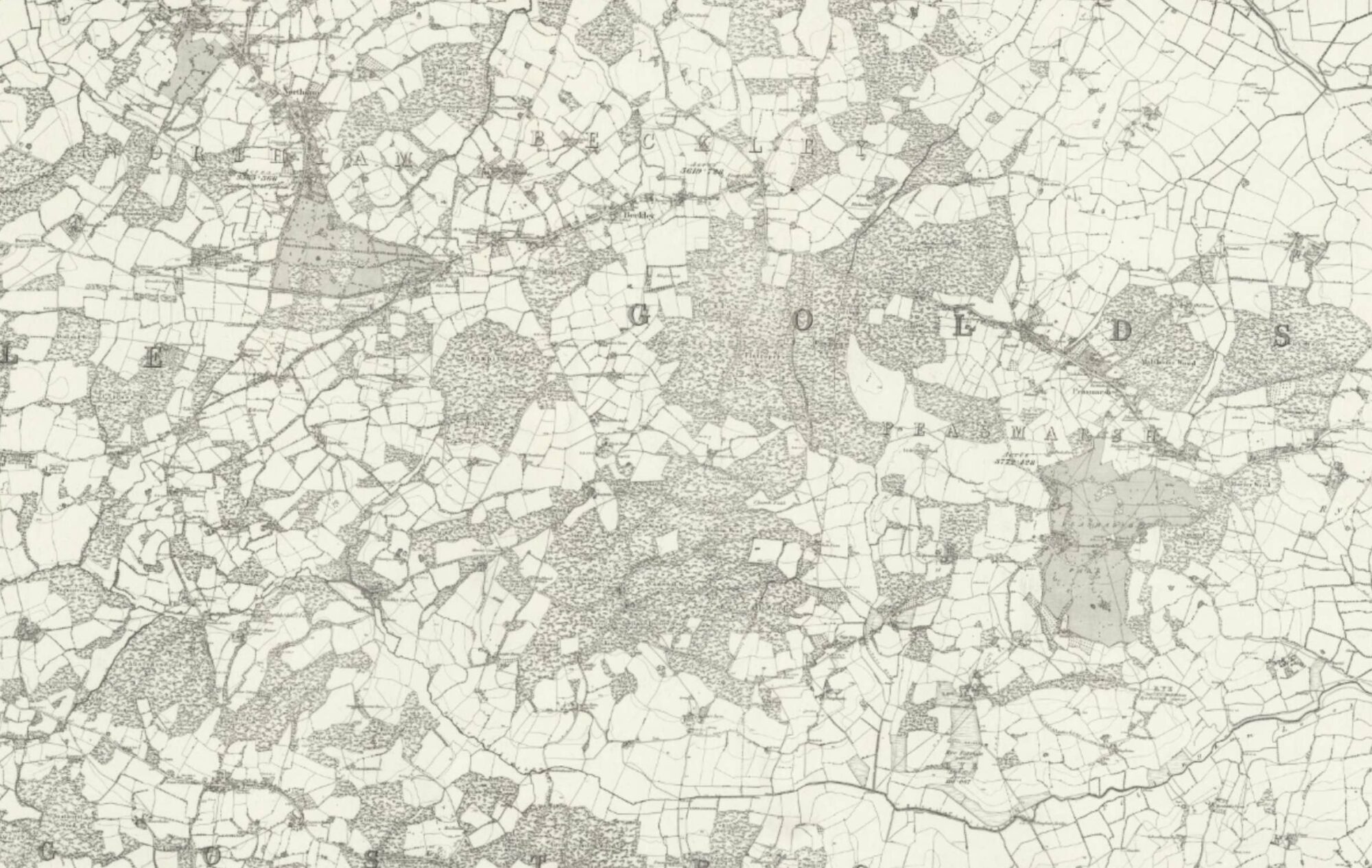

A young lad by the name of William Paine Furner enlisted in the British Army as a boy soldier in 1867. He was 15 years old. He trained to be a gunner in the Royal Artillery and was later based at Shoeburyness, a garrison near Southend-on-Sea at the southeastern tip of Essex. There the sea goes out for a distance of four miles at low tide, revealing mostly firm sands which were used in a marked off area for gunnery practice. He rose to Sergeant RA at Shoeburyness and his constant companion was William John Mason, also a gunner RA.

There lived in Southend—or rather Prittlewell as it was incorporated at the time; Southend had to wait until 1892 to confirm its own identity—a well-known citizen (Councillor, Alderman and Mariner) by the name of William Thomas Bradley. He had four children, the two youngest being Jessie Elizabeth (1854-1925) and Ellen Catharine (1856-189?). Our gallant Gunners met these two young ladies and fell in love: in June 1875 Sergeant Furner married Ellen Catharine Bradley and the following year Gunner Mason married her elder sister Jessie Elizabeth Bradley.

William and Ellen were based at Shoeburyness until 1891 and five children were born there. Three daughters were born in 1876, 1877 and 1879, by which time William had been promoted to Staff Sergeant. In 1881 he made Sergeant Major and in 1882 their fourth child—William Paine Jnr—was born. In 1888 another boy arrived and William was commissioned. Thus he was now Lieutenant, Coast Brigade, RA, aged 36 and with 21 years of Army service behind him.

In 1891 a very important new phase of his life was to begin. He was posted to Cork, Ireland, as District Officer and for the following eight years he remained in what must have been a tense and difficult assignment, particularly bearing in mind the friction between Ireland and the “mother” country, Great Britain, friction which was only partially resolved by partition in 1921. Certainly as an Officer in the British Army he would have enjoyed in Cork a comparatively comfortable life-style, with work place in what is now known as the Michael Collins barracks and quarters in the Governor’s House. However, soon after his arrival in Cork, his domestic arrangements took a serious turn for the worse: it has proved impossible to confirm the exact chain of events but, based on the available evidence, I believe that there can have been only two possible scenarios.

Scenario No 1:

His wife Ellen fell ill and her sister Jessie, who was now a widow with four children—William Mason having died in 1886—came to Ireland to look after her. Ellen died, at which point Jessie returned to England to collect her children before going back to Ireland once more. Whether there was a “marriage” as such between William Paine Furner and Jessie Elizabeth Mason is not known. If there had been it would have been illegal under the then marriage consanguinity laws. [The Deceased Wife’s Sister Act in 1907 subsequently made it lawful.] There was certainly an intimate relationship within which Jessie Elizabeth changed her surname to Furner and within which at least two further children were born. William was to describe himself 11 years later on another marriage certificate as “widower of Ellen Bradley, died 1891”: however, there has been no trace of her death in the UK, nor in Dublin, Cork or Army records.

Scenario No 2:

Long before, it had been William John Mason who had effected the initial introductions to the Bradley sisters Ellen and Jessie. We already know that Furner married Ellen and Mason married Jessie. At some time after Mason’s death in 1886, Sergeant Major Furner had an affair with Jessie. Jessie confronted Lieutenant Furner soon after his posting to Ireland with the news that she was pregnant by him. Ellen left him, taking two sons with her and leaving the daughters with their father. Jessie then stayed on with William and took the name Furner. There is no evidence of any of this, just as there is no evidence of Ellen’s death in either Ireland or England. It is remotely possible that she took a ship to the USA.

One of these two scenarios must be the right one. Whichever it is—and with the most rigorous research my brother and I have not been able to confirm one way or the other—it is clear that Lieutenant Furner was now living not with his legally married wife Ellen, but with Ellen’s sister and the widow of his colleague Mason, Jessie Elizabeth. We know that from that union came two more children—Evelyn (William’s sixth and Jessie’s fifth) who must have been born either in 1891 or 1892 and who died aged three in February 1895; and Vivian Jack (7th and 6th respectively) in 1893. There is no trace of birth of Vivian Jack in UK Registries, or in Army records, or in Dublin Registry or in Cork Registry. However, I later researched World War I papers on Vivian Jack in the Public Record Office at Kew and he himself declared his birthdate—in Cork—as 7th February, 1893. Vivian Jack was my father.

In 1899 Lieutenant William Paine Furner was promoted to Captain (RGA) and posted to Chatham as District Officer. This must have been purely a holding post, since in April of the following year he was posted again, this time abroad to Gibraltar as Armaments Officer. The Boer War was on, and Gibraltar would have been an important staging post for supplies and equipment of all types en route to South Africa. It seems clear from what followed that he must have left all family connections behind him—both his own large family and that of Jessie Elizabeth—and went alone to Gibraltar. Indeed, what followed was really quite sensational.

In May 1902 he was promoted to Major. In those days of rigid class divisions it was a notable achievement for our boy soldier, who had spent 21 years in the ranks, to have reached even the lowest level of the “senior officer” ladder. Alongside his duties as an Army Officer in the middle of a long-distance war, he cultivated friendships amongst the local society. He met a young lady—she was 24—named Maria Luisa Martinez. They were married with great ceremony in two cathedrals on 11th September 1902, first at the Cathedral of St Mary the Crowned and then at the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity. The “Expediente Matrimonial” form shows William Paine signing himself first as “Saltero” (bachelor), then erased and superseded by “Widower of Elena Bradley, died 1891”. The marriage ceremony was described in some detail in the following day’s edition of the Gibraltar Chronicle:

“The wedding of Major W P Furner, of the Royal Artillery, to Miss Martinez, of this City, furnished the occasion for two very pretty ceremonies yesterday … Both Cathedrals were filled not only by the numerous friends of the bride and bridegroom, amongst whom we noticed several officers in uniform, but by a large crowd of interested spectators also. The bridegroom wore the full uniform of his rank, while the bride was richly and tastefully attired in ivory white satin trimmed with lace and chiffon … A reception was held afterwards at the Grand Hotel and some 60 guests sat down to a recherche breakfast well supplied by that excellent caterer Mr Posso. The toast of ‘Health and Prosperity to the Bride and Groom’ was proposed by Major Churchill RA. The happy pair left by the 4.30 pm boat for a tour of Spain … The wedding presents were numerous and handsome, an eloquent testimony to the esteem of a large circle of friends and well-wishers which included Major General and Mrs John Bally …”

A great day for the Major. One must wonder, however, with what level of “esteem” the Major was now held by Jessie Elizabeth and all the children he had left behind in the UK. We do know that Jessie sought financial help from her father, by now Alderman Bradley; and it has been reported to us that she wrote to Field Marshal Sir George White, Governor of Gibraltar 1900-1905, in the hope that he might be able to do something about her plight after William Paine had deserted her, but we have seen nothing in writing to support this.

Two months after the wedding the Major retired from the Army, at age 50, thus having served for 35 years. He and his very young bride returned to England and he immediately drew up his Last Will and Testament, leaving all his estate to Maria Luisa Furner. From that point on, I have clear evidence of his Army pension being paid to various addresses—Harringay, Brighton and St Leonards. There is also evidence of his attendance at the weddings of one or two of his daughters. His life went on quietly in Sussex and we reach the point at which this chapter began—the wedding of Vivian Jack Furner, my father, to Elsie Georgina Potter in August 1921.

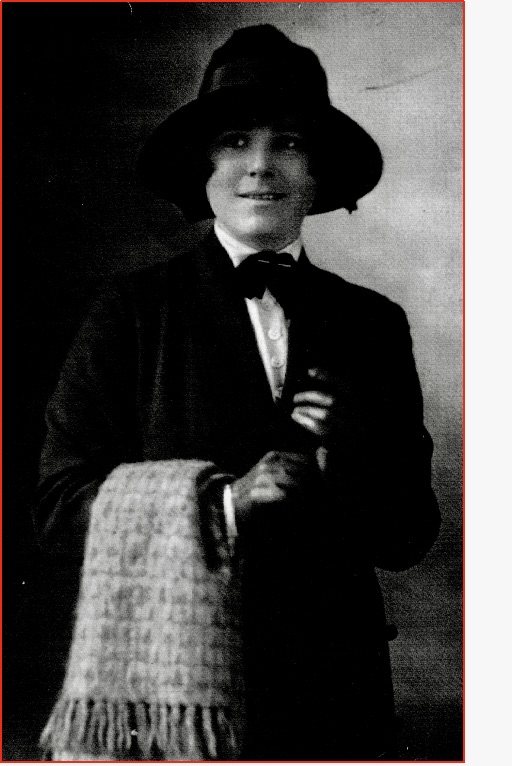

We—my brother Ken and I who have tried to piece this story together in the 1990s (our 70s)—believe that Jessie, the groom’s mother, who was now living in Hadleigh Essex, was not happy about the marriage. Elsie was in the 6th month of pregnancy; Jessie considered the match as unsuitable; George Potter, Elsie’s father—a kindly man to whom integrity was all-important—had made it crystal clear that there could be only one outcome; Vivian Jack’s mind must have been in a whirl.

As for William Paine Furner, he was an outcast as far as his previous family was concerned and Jessie pronounced him dead at the time of the wedding. Indeed, the marriage certificate labels him quite specifically as “deceased”. At the time, unbeknown to many at the ceremony, he was in fact living in St Leonards with Maria Luisa, enjoying an Army pension of £200 per annum.

He was to live another 11 years in Sussex. In fact, but for a few months, we shall see that he almost outlived his son Vivian Jack. Whether Vivian really knew his father was alive during those 11 years, none of us will ever know. Indeed, whether Vivian Jack ever knew his father at all is a moot point: he was deserted by William Paine before his sixth birthday and was then brought up solely by Jessie Elizabeth, along with his older step-sisters Violet, Beatrice and Daisy. They all returned to England in 1899 and set up home in Hadleigh near Jessie’s parents. Vivian Jack attended Technical School and St Johns College in Southend and was later employed by Southend Corporation as Clerk and Cashier. My uncle used to describe to me his admiration for Vivian’s skill at adding up three columns of figures (£, s, d) in one sweep.

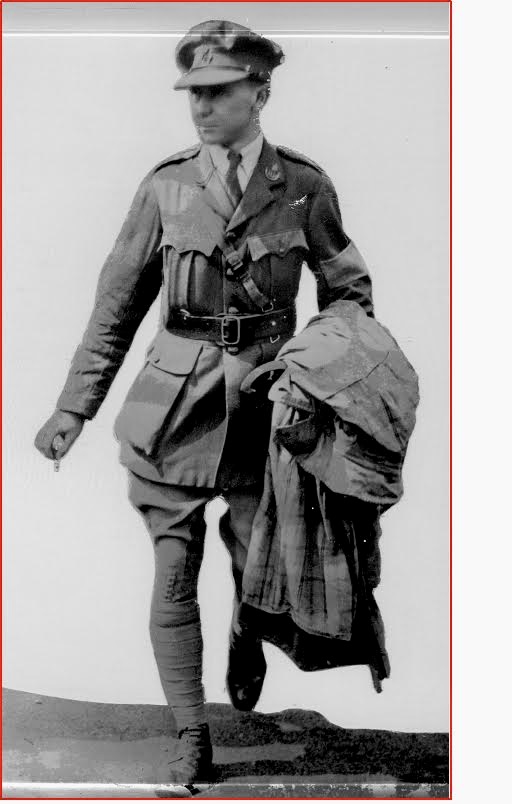

Then the “Great War” began: Vivian enlisted in the Army in February 1916 and joined the Durham Light Infantry. In France, a Sergeant in 1917, he applied for a Commission in the Labour Corps. As a 2nd Lieutenant in 1918, whilst in Belgium, he was wounded in the left arm, repatriated, and awarded leave and a wound gratuity. Demobilised in April 1919, he returned to his original employment with the Southend Corporation. He met and fell in love with Elsie Georgina Potter and when they married in August 1921, she was 21 and he 28.

I was born three months later.