The year 1921 was a “bulge” year. There were a lot of us born that year. Things were slowly getting back to normal—but hardly a “normal” any of you would recognize—after the four years of “The Great War”, ending in November 1918, which most of your history books will now refer to as World War I or WWI for short. The “I” became necessary because “II” started by the time I had conveniently reached the age of 18—but more on that later. That 1921 bulge, by the way, turned out to be of rather more lasting interest than just a blip on a statistician’s graph: believe it or not, it exercised me in my work 45 and 53 years later.

But let’s get back to childhood. My memories of the first five years are almost non-existent. Maybe you’ll find the same problem when you get to my age. In fact, I have only one memory which I’ve been assured happened before the age of 5—and that was of being dropped on my head on to the wooden slatted floor of some sort of hut somewhere on a beach. Well, we were a beachy family: bound to be when you live in a place like Southend.

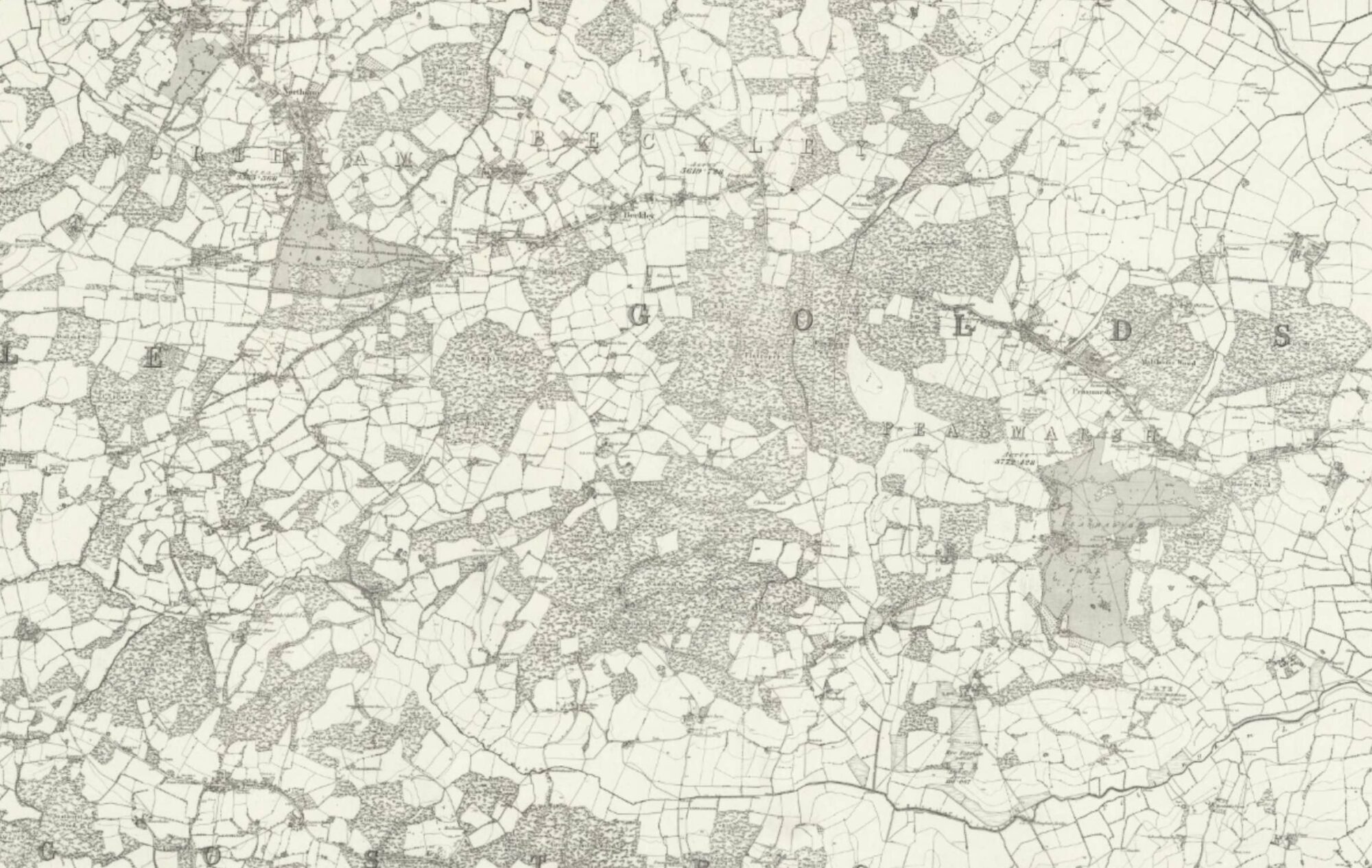

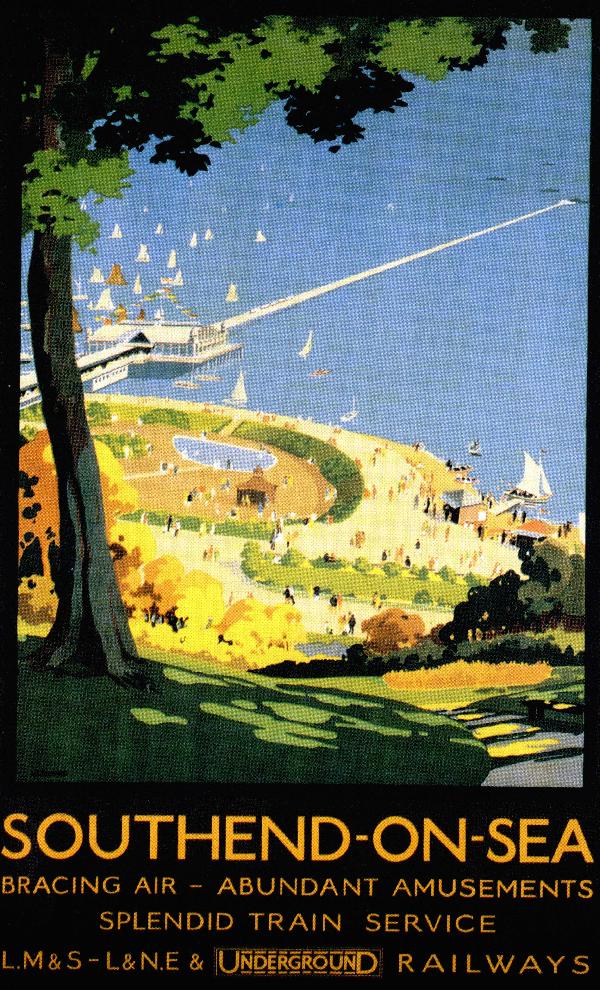

Or should I say Westcliff? You see, Westcliff was to Southend as Hove is to Brighton and St Leonards is to Hastings—the “nicer” end. In fact it seems I was born a bit outside both: my birth certificate, which I had to seek a copy of when I was about 60, says I was Derrick Jack, son of Elsie Georgina and Vivian Jack, residing in Beech Cottage, Beech Road, Hadleigh. The date was 14th November 1921: my mother, as I have said, was 21 and my father was 28. He was an accountant working at the Borough Treasurer’s Office in Christchurch Road, Southend. Of course I remember nothing of Hadleigh—the address on the certificate came as a surprise to me—nobody had ever mentioned the place. I assume therefore that we must have moved pretty smartly to the first address I do remember—188 Westcliff Park Drive, Westcliff. It was a terraced house—today we’d describe it as a 2-up, 2-down—and like the majority of people in those days we rented it from a landlord.

I have lots of memories between the ages of 5 and 10 in Westcliff Park Drive. They can be arranged and rearranged as with the patterns in a kaleidoscope, but not, I’m afraid, be put necessarily into a logical and chronological order. You as the reader may find this irritating. On the other hand, you may understand and be tolerant: let’s hope so. As all the years and the decades have gone by since those early days of childhood, there is one very sad thing that keeps on surfacing: I remember nothing—and I really mean nothing at all—about my father, Vivian Jack. I can’t see his face, nor his figure walking, nor recall any conversation, nor any game, indoor or outdoor. Even when we were on holiday—for instance at Littlehampton, or Margate, or Ostend (!), we did nothing together. I remember trying to swim but he made no attempt to advise or help. I can’t even remember any anger or remonstrations. And by the time I was 11, he had gone for ever.

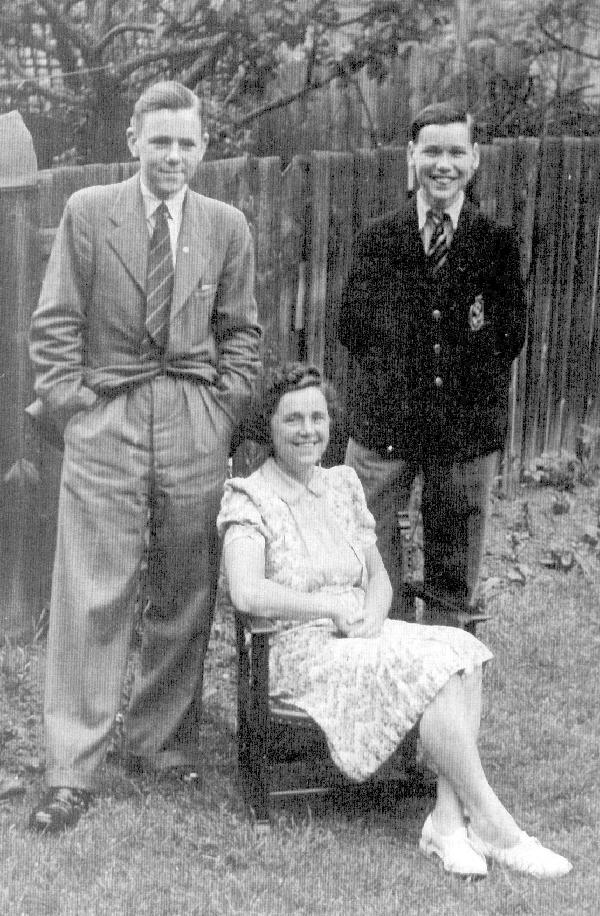

Maybe he was a very busy chap: but I’ve been busy in my life and I’m sure my sons would have remembered something of me. He used to take my mother to the cinema every Monday and Thursday evening (there were 15 cinemas in the Borough of Southend in the early 1930s) but he never took me, for instance on a Saturday morning or afternoon. If I could wheedle enough pocket money out of my mother I would go with other boys. In fact, the only time I can remember going to the cinema in the same group as my father was when we visited some lovely relatives of his who lived in Reigate—we went as a large party to see “General Crack” and it was magic. It’s funny but I can remember more childish joy away from home, at relatives of either of my parents: sad, but there it is. I’m sure my brother Ken, who was four years younger than I, would say the same.

Any errands I was sent on were on direction from mother, never my father. To take the “accumulator”, for instance—this will amuse you children of the 21st Century—from inside the huge radio down to the shop at the corner of Westcliff Park Drive and Fairfax Drive, so that it could be exchanged for a freshly charged one while ours was charged. You see, the electrical power for the radio consisted of a wet battery—the accumulator—which looked like half a car battery of today; and a dry battery which was almost as big as the two halves of the Concise Oxford—and as heavy. As you will now understand we didn’t power it from the mains. We had electric light and, apart fom one gadget, that was all; some houses didn’t even have electric light in those days—some were still on gas lamps. The only electrical gadget we sported was a cylinder vacuum cleaner. The house was on a “flicker” system to save electricity (and money)—put too many lights on and you had everything flickering; the flickering could be halted only by switching off the excess wattage.

School was Westborough, a mile away. I used to walk through the alley-ways to get there, parallel to London Road and Fairfax Drive. I was there from the age of 5 to 10. I think my mother escorted me there once only, the first day. I enjoyed every minute of it.

Westcliff was joined to Southend one way and Leigh the other by a tramway system which rattled along the main London Road. They ran on rails in the roadway and were connected to overhead electric power by a long arm which was sprung to push upwards. At the end of a run the conductor would get hold of a long pole and swing the arm round so that the driver could start driving from the other end. They had two decks and had the look at least of being a bit top-heavy; but there were never any incidents.

Walking across the London Road and heading south towards the Thames, down Crowstone Road or Valkyrie Road, soon brought you to the river. The river was so wide at this point of the estuary—7 miles—that it was for all intents and purposes the sea. And in the summer it was wonderful. No matter that Southend attracted the “day trippers” from London—the seafront was alive, and gay (please may I continue to use that nice little word?), and colourful and exhilarating; and of course there was the longest pier in the world—one mile and a third.

To our north, beyond Fairfax Drive, were all fields and trees to climb. One day in the early 1930s a Tiger Moth landed in one of the fields out there (the Southend General Hospital has been on that spot for the last 50 years, but then it was just a field) and we children went rushing, as if called by the Pied Piper, out to the field to see this extraordinary event. From all the streets we came, and like tributaries to a river, we gradually reinforced each other. A great crowd eventually surrounded the tiny aircraft—a big event, a great sight. Flight was then an unknown to all of us. Within little over a decade it was to mean a great deal more to all of us, and in particular to me.

Between the ages of 5 and 10 you don’t take much notice of politics and all that, do you? I’m wiser after the event in my old age, of course. But then, the General Strike of ‘26 meant nothing to me—my father may have driven a bus for all I know, but probably not because he never owned a car. The Wall Street crash of ‘29 passed me by; the Great Depression that followed in the early ‘30s troubled me not at all. We were comparatively poor, and enjoyed simple things, but it was the same for everybody we knew. Nobody owned a car, or a refrigerator, or a washing machine, or a camera. The words television, computer, recorder, dishwasher, microwave and so many others were not in our vocabulary. There was a mangle for squeezing water out of washed clothes; there was a wind-up gramophone for playing a 78 rpm record of Caruso singing Vesti la Giubba. And there was a radio, in an enormous box, powered by the wet and the dry, on which we listened to the National programme or the London Regional Programme.

My principal concern when I reached 10 was how I would get on in the Scholarship exam for the prestigious (to me and the family) secondary school called Westcliff High. It was a sort of Holy Grail and I just had to do well. It was the first of many educational hurdles. The point was that in those days many parents paid for their sons to go to Westcliff High: there was no question of mine doing so, hence the importance of the exam. Well—it was all right—I got a scholarship. What a feeling of being on top of the world, just for a little while, until the greater hurdles of the future slowly came into focus. Entrance was to be at the end of a long summer holiday in 1932: last-minute panic on the right clothes, blazer, tie, grey shirts. I can’t remember my father taking any interest though. Presumably he must have been pleased.

The new school was bewildering to start with—aren’t they always? It all seemed so new. It had been built as recently as 1921; Mr H G Williams, a portly figure, was the first Headmaster; all the blackboards smelt of new paint in each September; the classrooms were grouped around two open quadrangles with a large assembly hall between them; the masters wore their gowns; the prefects sported piping around their blazers. There were lots of new and interesting friends, many of them as highly competitive as oneself: unsettling in one sense, challenging in another. But I had been there only one short term when tragedy struck my parents.

The story that I have been able to piece together since the events of January 1933 went like this. My father had been playing golf with a friend—they were both members of NALGO which in those days was really an A for Association and not one of the front flag-bearers of the TUC—and he got wet feet in bad weather and caught a cold. The cold developed into something much more serious and in time he had double pneumonia and pleurisy. There were no known drugs in those days to fight such conditions. The body had to struggle through on its own. He lay upstairs in the front bedroom of 188 Westcliff Park Drive and sweated and tossed through his fever and delirium.

At some climactic point—and opinions vary as to what was in his mind at the time—he rose from his upstairs sick-bed, walked to the window facing the street, opened it, jumped from it to the tiny garden below and, still miraculously able to move, tried to make his way across the street to get to the front door of the house of his sister, my Aunt Beatrice (Beattie). The alarm must soon have been raised for an ambulance. I remember coming upon the scene with people all over the street, outside our house and outside Beattie’s, with a general hubbub and an ambulance about to leave. I don’t know where my mother was; I think I was taken indoors by Beattie and her husband Tom. For an 11-year old it was horrific.

My father was taken to hospital and died there a few days later. He was 39 and I knew so little about him. My mother cried out his name—Jack … Jack—at night for weeks afterwards. The local weekly newspaper The Southend Standard printed an obituary:

“Corporation Official’s Death. The death occurred on Thursday (12th January 1933), at Southend and Municipal Hospital, at Rochford, of Mr Vivian Jack Furner, a popular member of the audit staff of the Borough Treasurer’s Department. Mr Furner, who was in his forthieth year, was a keen golfer, and it was following a round at Belfairs Golf Course, nearly a fortnight ago, that he was taken ill with influenza. Later, pneumonia developed, and on Saturday week his condition was aggravated by an accident. He was subsequently removed to the Municipal Hospital on an ambulance. Much sympathy will be extended to the widow and her two young sons in their sad bereavement. The funeral took place at St Johns Churchyard, where Mr Furner’s mother is buried, on Tuesday, following a service in the Church, conducted by the Vicar, the Rev J Whitehouse. The family mourners were: Mr Potter snr (father-in-law) and Mssrs J Smerdon, T C Smith and Mr Potter jnr (brothers-in-law); there was also a large attendance of friends and of the deceased’s colleagues of the Corporation Audit Office. The deceased, during the Great War, was a lieutenant in the Durham Light Infantry and was wounded on the Somme.”

The minor errors concerning his war service are unimportant. What was extraordinary was that he died less than ten months after his father who for all intents and purposes had not existed in Vivian Jack’s life since 1899. William Paine Furner had become senile in the last few months of his 80th year and had died in a Hospital at Hellingly near Eastbourne.

His wife, Maria Luisa, lived on until 1954 and died in Brighton leaving an estate of £9 1s 3d.

***

The tragic death of my father changed my mother’s life. She was widowed at the age of 32 and had two sons to bring up. Money was short. The first decision she made was to move—to another private rented house, terraced 2-up 2-down, in the next street parallel; our new address was 102 Beedell Avenue. I remember our Manx cat kept wandering back to the old house and I’d have to go and look for him. My bedroom was a tiny little box-room and I can still see in my mind’s eye the thick frost which formed on the inside of the window during winter cold spells. Each morning I would awaken with my eyelids tightly closed by a gluey substance which could be dispersed only with boracic solution; much later in life I knew this to be a symptom of blepharitis.

Once settled in, mother buckled down to the only way she knew to increase her income: she started taking in lodgers or “paying guests”. We had them in the house for many years. Some were great fun around the meal table; others were pompous and made Ken and me snigger, much to mother’s embarrassment. I seem to remember most of them were involved either in local government or in teaching. Some stayed a long time, others only a few weeks. One—John Franklin—stayed permanently and later my mother married him. Until then, and certainly throughout my schooling, it must have been a constant struggle for my mother, cooking, cleaning, washing, seeing to the needs of at least two lodgers at all times as well as looking after two sons.

Sadly, we two sons didn’t mix much. The age difference was just big enough for us to have our own circles of friends, in different schools, of different backgrounds; by and large in the 1930s we went our separate ways.

The all-important feature for me from 1932 to 1939 was school. I was dedicated to it, it was my whole life, I loved it. I must have seemed a prig and a swot to others in the family circle; but that school was a different world, with competitive people all around me, eager to surmount whatever hurdles were presented to us.

The school was arranged from Forms 2 to 6: 2,3,4 all had streams A,B,C,D. Forms 5 split into Arts and Science, then B,C,D: it was at this level that we took our General Certificate (what became O Levels and later GCSE). Assuming success in the General, on to 6—Arts, Science or Commerce—for two years more work before taking the Higher Certificate (A Level). Fortunately I started in the fast stream, in 2A, and stayed there with a dozen or so others all the way up the line—Bestley, Boff, Byfield, Clark, Crowe, Dawson, Furner, and so on … Since most of these chaps were 11 on entry they were ready to take their O Levels at 15: I was just a bit younger, still 10 on entry, hence got to tackle the Os at 14.

The Masters were constant throughout my seven years: I can recall no changes except on reaching the Sixth, even then only because of an unusual A Level combination of Languages and Maths. They were all so dedicated, so memorable, so understanding. Midgeley for English, H S Smith for Maths, Budworth for French, Brown for History, Ruffhead for Spanish, Harden for Latin, “Chemy” Smith for Chemistry, I can see them all, I can hear them all. Midgeley instilled in me unforgettably the construction of a sentence, parsing and parts of speech. I can see H S Smith drawing on the board the wonderful proof of Pythagoras. Budworth endeared us to so much of French Literature as well as putting over the language so sensitively. It was best not to be in the front row for Spanish: Ruffhead lisped and the Spanish language gave him full scope. Harden was splendid at rehearsing our amo, amas, amat, but sadly didn’t like taking on also the branch subject of Roman History and it showed.

The terms went by, the years went by, the exams came and went. Exams were challenges—swotting, revising, sitting, divide up the points, allot the time, check all the work in the last minutes, discuss afterwards—oh no!—missed the point of that! The essential thing was that you gradually developed an exam approach which stood you in good stead against later challenges both at school and in career.

In my spare time, both during term time and holidays, I sought out jobs to give me pocket money: a bread round, sometimes having a go at driving the electric van; a milk round, for which I did most of the work, in fact, even to the extent of pulling the trolley; the odd paper round; and, in the summer holidays only, handing out claim slips for those on the seafront who had been photographed as they walked—that photographer still owes me half a crown, work that out with inflation! I used the proceeds mainly to go to the cinema. As I said, there were 15 of them in the Borough, and I knew them all, from flea pit to the brand new Odeon. Fourpence (1.7p) at the Gaumont was good for 2 films, the Gaumont-British News, a cartoon, an organ recital and a short stage intermission. They were the days of the huge Hollywood Motion Picture companies—MGM, RKO Radio, 20th Century Fox, Paramount, and so on. Queues lined up for Astaire-Rogers, for the Frankenstein series, for Alexander Korda films: for instance, the historical fun of The Private Life of Henry the 8th and the terrifying excitement of Things to Come in 1937. [In early September 1939 it was due to have a second run at the Kursaal but was taken off as being too near the truth!] It’s funny how one can remember the names of Hollywood’s supporting actors, stalwarts like Franklyn Pangborn, Eric Blore, Edward Everitt Horton, Mischa Auer and Una Merkel—not big names, but always turning up and being themselves every time. The school encouraged us to see foreign films from time to time, mostly French; Carnet de Bal and La Femme du Boulanger were unforgettable. Increasingly during my teens, I learned also to extend my listening—mostly appreciative—of classical music.

I wasn’t particularly good at any sport. I took part in cross-country running; I got hit on the head by a cricket ball; I suffered squashing in the scrum on the rugby field. As I grew up and entered the Sixth and became a prefect, I tried to do my bit by scoring for the first eleven and acting as touch judge for the first fifteen. Extraordinarily the combination of these peripheral activities and other general interest societies brought me the award in my last year at Westcliff of what was known as the Dowsett Cup, named after a previous Mayor of Southend. I was the last one to hold it before the War began, and the School didn’t ask for it back until 1945: I was in the Far East at the time.

Mention of the War brings me to the more sinister side of our lives in the 1930s. How to describe to today’s youngsters what those days were like? Understand that I was just getting into my teens when the international scene took a series of ominous turns; and realise that there was not then the instantaneous visual playback of everything significant that was going on in the world. As the decade progressed the sense of increasing international instability, tension and, yes, plain old evil, became more and more oppressive in our lives. In 1933 Adolf Hitler took over the permanent and unopposed control of Germany, still seething after only 14 years from the effects of the punitive Versailles Treaty. For the next six years the newsreels featured many scenes of massed ranks of obedient soldiers with their arms raised in salute and their shouts echoing around vast concourses. In 1936 Hitler marched them into the Rhineland; in 1937 his Air Force bombed Guernica to aid General Franco in the Spanish Civil War and the Japanese Air Force bombed Shanghai; in the spring of 1938 Hitler, cynically seeking more lebensraum, invaded Austria; and in the autumn of 1938 took over the Sudetenland, part of Czechoslovakia; in the spring of 1939, tearing up an agreement made in Munich with our Prime Minister Chamberlain (J’Aime Berlin was the cruel joke at the time), Hitler invaded the remainder of Czechoslovakia; finally, in the autumn (1st September) of 1939 he—and the Russians! (a few days after a non-aggression pact was signed by Ribbentrop and Molotov)—both invaded Poland. That was it. The United Kingdom could not allow it. On Sunday, 3rd September 1939, a balmy warm day with scattered cumulus clouds, Chamberlain told us all at 11.00 am that “a state of war now exists between ourselves and Germany”. The “Great War” now had to be renamed World War I. We were about to embark on World War II. Fifty million people around the world were to lose their lives.

By that date, I had now left Westcliff High with my Dowsett Cup and a string of A Levels and had been “arranged” to occupy a post in the Imperial Bank of India in Old Broad Street. Banking in those days was considered to be a fairly up-market career, and this particular Bank carried a certain “imperial” prestige about it which many lesser lacked. All the staff were British (not so now, as the State Bank of India). Of course I started at the bottom as a general dogsbody—for instance, at the beginning of the day dealing with the mail in and at the end of the day with the mail out. Mind you, the early event could be profitable: if large packets came in from Delhi, Peshawar or wherever by airmail, they would be covered with fairly expensive stamps which were sufficiently sought after by local philatelist establishments to add a few pence to the £2 a week gross salary. It was fun while it lasted and I recall with pleasure the people I worked with. My very good friend George Thomson was one of the staff, in his forties, a bachelor with a roving eye and a fund of stories of the major ports of the world (he had spent his youth in the Merchant Navy); whereas many of the other staff were a trifle stuffy and staid and had little but trivia to talk about, he and I would discuss music, the theatre, the cinema; and it was he who first instilled in me an admiration for the New Yorker magazine, sample works of which I’ve long held on my book shelves.

After the “phoney war” period during which nothing much happened, things hotted up in April 1940 with a succession of invasions—into Denmark and Norway, then into Benelux and France—which brought the word blitzkrieg into the newspapers and our conversations. The Wehrmacht made sure that 1940 was not to be a repeat of 1914. The invading hordes swept westwards like a huge scythe; the British Army was cornered at Dunkirk and had to be evacuated; and, despite a last minute offer from Churchill of dual citizenship, the French collapsed. With their surrender in July, the United Kingdom was on its own (Very well—alone declaimed the political cartoons) and everybody prepared for bombing and invasion. The sense of isolation was alleviated by the eager support of the old dominions who were mobilising to come to our assistance.

I have two vivid memories of the ensuing six months. Firstly, at weekends, to the east in Southend, I would watch as the sky filled with German bombers, in formation, not very high, the fearful drone, heading west up the estuary where our fighters would be waiting for them. I had never seen so many aircraft at one time in daylight. Secondly, when the Luftwaffe made the extraordinary mistake of switching from attacking RAF airfields to night bombing of London, it would often be a slower journey to Fenchurch Street station the next morning because of craters near the line, then a surreal walk from station to Bank through debris and water hoses and around bomb craters; staying overnight from time to time according to rosters of fire-watching; George Thomson would usually make sure we were on together.

I have often wondered what sort of career I should have had if I had stayed in (or returned to) the Bank—presumably a fairly lucrative one in finance. It was not to be, of course. I realised that it would not be long before I personally was caught up in this war; but it did not occur to me during the London “Blitz” that, within a few months, I would be starting off on the path of contributing to even worse fires and craters for the enemy.