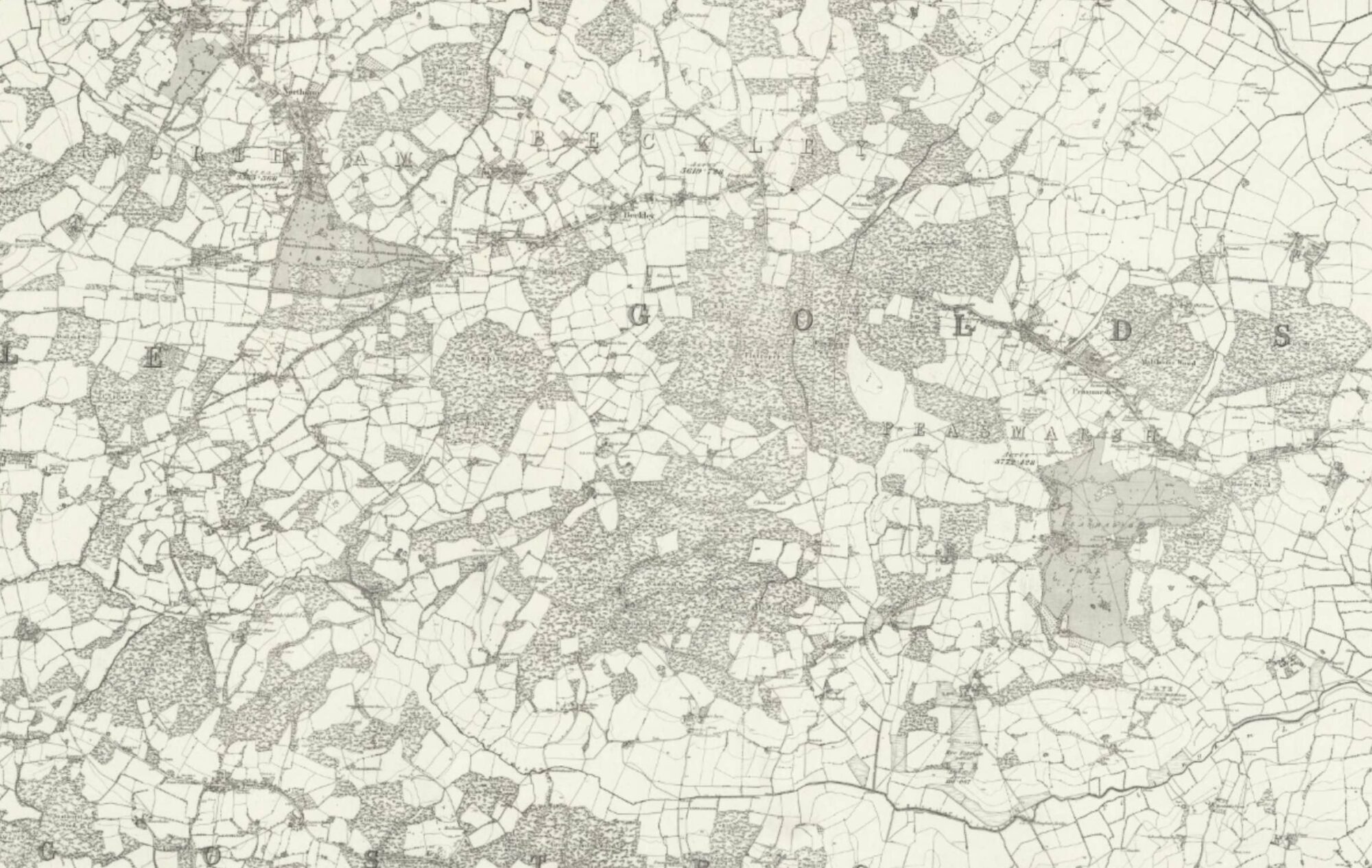

In early 1943, as it had been since the London blitz, RAF Bomber Command and certain Groups of the USAAF constituted the only offensive action against Germany; and so it was to be until 6th June 1944. There were six Heavy Bomber Groups established in Bomber Command. Nos 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 (Canadian), and 8 (Pathfinder Force). No 2 Group consisted of medium bomber Squadrons, principally Blenheims, Mosquitos and Venturas. Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris had been Commander-in-Chief since February 1942 and would continue to be so until the end of the war, following directives from Air Ministry based on policies of the War Cabinet. Four-engined aircaft were joining the Heavy Bomber Groups in increasing numbers—principally Halifaxes and Lancasters. The Stirlings, the earliest of the four-engined, were all in No 3 Group in East Anglia, whose Headquarters was at Exning near Newmarket. John Verrall and his crew were posted to the strength of No 214 Squadron at Chedburgh near Bury St Edmunds in March 1943—22 months after I had joined the queue of recruits at Lords. I used to say “Verrally, thou shalt operate”. Our tour on the Squadron was to last only five months.

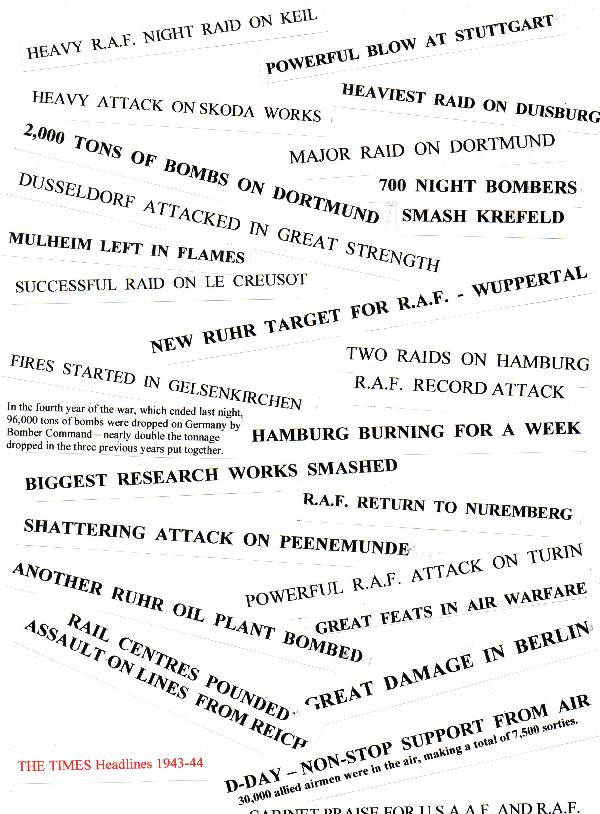

Our first operational target was Kiel on 4th April, the last Berlin on 31st August. It was a hectic summer. In between first and last came most of the targets in the Ruhr, some repeatedly—names like Duisberg, Dortmund, Dusseldorf and Wuppertal; and Hamburg (several); Turin; Peenemunde (most memorable); and Krefeld, Mulheim and Nurnberg.

There were also mining sorties (codenamed “Gardening”) in the Baltic, off the Frisians and in the mouth of the Gironde River. In between operations there would be a lot of local flying—air tests, circuits and bumps, practice bombing, simulated sorties, fighter affiliation, familiarisation with new aids, and so on. The total number of Stirling flights with No 214 in my log book is 120, of which 25 were operational. As to the “new aids” the most significant was the equipment contained in that pregnant bulge we had seen at Waterbeach. It was called H2S. It was an airborne radar with a rotating parabolic dish inside the bulge which interpreted the ground beneath on a cathode ray tube at the navigator’s station, differentiating between dark (no response) for sea, some bright response for land and brighter response still for built up areas. It was a marvel to see then, but it was crude, and because it was transmitting, it drew attention to itself. This airborne radar came into the Squadron at the beginning of July and I was chosen to train other navigators on it.

It is well nigh impossible more than 50 years later to describe in detail each one of the nightly battles—and battles they were. It happens inevitably that so many things are blurred, except for a few really dramatic moments. I can more easily picture in my mind, and try to describe in writing, a typical—or average—operation, rather than any one specific instance.

The average or typical begins with the briefing. Navigators always had a lot more preparatory work to do than other crew members and would have to assemble for their detailed planning of log and chart a good hour before the remainder of the crew came in. By the time complete crews were sitting to hear target details, outline of route, markings, weather, defences, bomb load, fuel, signals, encouragement from Commanders and any visiting brass, the navigators would have log flight plan and chart ready. Always at the specific request of my skipper I would have the fighter belt pencilled in: he would wish to corkscrew all the way through it, regardless of whether there had been any sightings. Assemble all kit—parachute, Mae West (what fame!), sextant and navigation bag with log, charts, maps, star data, protractor, Dalton “computer” (!)—simply a graphic representation of the triangle of velocities—dividers, parallel rule … Out to the aircraft at dispersal a good hour before take-off. Run engines. Thorough checks all round each member. I check all navigation equipment—compasses, Gee, H2S, air position indicator, astrograph (a star map), sextant. Shut down. Last smoke and symbolic pee on the tail wheel. Back into that storeys-high cabin of the Stirling. Smells of petrol, and oil, and hot metals. Engines—pilot and bombaimer go meticulously through take off checks. Line up—await green Aldis. Go. Down the runway, all four engines roaring and spitting flame, rotate. Climb at planned rate, with flight plan indicated airspeed and on planned course adjusted for magnetic variation and compass deviation. Cross UK coast at planned exit point and at planned height. Change course. Continue climbing across North Sea. Test guns. Passing through 10,000 feet, oxygen masks on. Keep continuous log on proforma, monitor airspeed and course, get fixes on Gee, check wind. Announce enemy coast ahead. Get fix from bombaimer crossing coast if cloud and visibility allow, check wind. Prepare skipper for fighter belt: corkscrew: accept that accurate recording of navigational path is now more difficult, as well as stomach more queasy. Other crew members report searchlights ahead or off route, or flak, or fighter activity, or ours going down. If somebody were to have switched daylight on at this stage, Heaven knows what we would have seen! Better this individual navigation, though, than the American way all in enforced formation. Too soon the GEE goes—jammed by Jerry. H2S remains but very difficult to decipher inland whilst corkscrewing. Trust to Dead Reckoning and Pathfinder markers at points along the route and at the target. Change course as demanded by flight plan. Reckon to be two minutes early over target? Make a triangle—60 degrees left for two minutes, 120 degrees right for two minutes, resume track. (The rest of the crew hated that—understandably.) Fighter!—call from rear gunner—much more violent evasive action to throw him off. Target approaches, markers, fires if visible; well lit cloud with markers above if not. Pilot responds to Bombaimer: left left or right or steady—interminable steady—come on, come on!—bombs gone. Course home. Caught in searchlight—brilliantly lit up, we’re vulnerable, frightening—violent manouevres—hold breath until darkness again. John’s got us out of it. Try to assess average airspeed and course during manouevres. Lots of flak—but we’re lucky, not a hit. Same thing all the way out back to their coast—only even more vigilant, fighters more evident. Comparative calm of North Sea, course for home base, descending, oxygen mask off, dirty mark around face, familiar red pundit light flashing, turn to land, breathe wonderful East Anglian summer air—“Another one tucked away, skip” shouts the rear gunner. Cigarette, debrief, meal, try to sleep as the sun comes up.

That paragraph represents a poor attempt to put an eventful 4 to 8 hour period on paper. What one’s thoughts might have been for what was going on below us is another subject which I’ll tackle later.

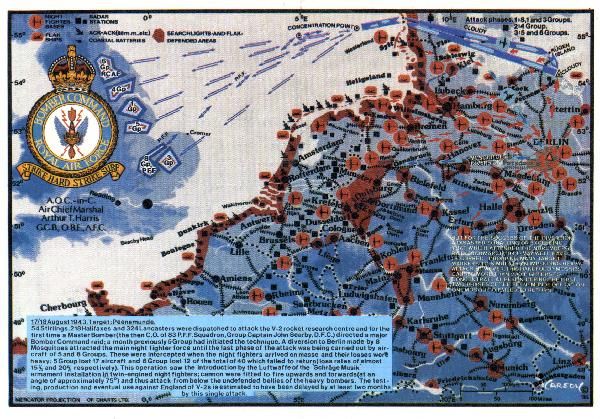

If I were pressed to describe specific raids, the highlights of my memory banks are: Wuppertal on a brilliant night seemingly going up in one awful pillar of smoke (“come and look at this, nav!”) (29.5.43); all the other Ruhr towns confused in one’s mind; the chaos below of Hamburg’s “firestorm” (27 & 29.7.43—also on battle order 24.7 but engine failure); the extraordinary beauty of the Alps in moonlight enroute to Turin (12.8.43). But the one that stands out above all others is Peenemunde 17.8.43—and for a number of reasons. It was to be our last but two, although we didn’t know that at the time. We were certainly reaching the slightly twitchy stage in the 20s. We were briefed that it was a scientific establishment making something or other that did not bode well for the UK. The briefing was highly unusual. Not a major city, with an aiming point somewhere in the centre, designed to take out as much industry as possible, but a strange place on the Baltic coast which none of us had ever heard of. “It’s a secret place where new experimental equipments are being developed”, the briefers said. There were a number of discrete aiming points (another unusual feature): ours was a particular part of the Experimental Establishment and other Group(s) would be targeting the actual living quarters of the scientists involved. We were to fly Stirling Z—EF404. We were to go in over the target at a much lower level than usual—at about 8,000 feet. And there was moonlight. “But there are only light flak defences”, the briefers said. The route looked nice—a quick dash across Denmark, through the Baltic and turn on to the target from a headland to the north of it, just a few miles from coast. A snip?—we thought. Not exactly: the intensive flak over the target was far worse than briefed—we were bouncing around on a dense carpet of it; and on the way home, flak ships accurately placed all the way along our track, or so it seemed to us..It proved all very tiring for skipper John Verrall. He lined up the aircraft for the final approach to Chedburgh exactly eight hours after take-off and ever so slightly misjudged his touchdown point on the runway. Proud old EF404 ran off the end of the runway and into a ditch. We were shaken but unhurt.

It was some time before we realised the importance of Peenemunde. It was engaged in the development of the V1 and V2 rockets. At least, on the night of 17th August 1943, we must have delayed their programme somewhat and ensured that London did not receive as many of them as Hitler would have liked. As an afterthought to the raid, I suppose it was useful to the US space programme that we missed Werner von Braun.

The new recruits to the Squadron were able at briefings to judge the difficulties to be faced by the reaction of the more experienced crews. The groans would be loudest in the briefing room for those demanding a long and deep track over occupied territory—eg Berlin and Nurnberg. The next worse would be all the Ruhr targets—much shallower penetration but fiendishly defended. And I suppose the lightest reaction would be for a peripheral target, like Kiel (our first) and Hamburg. This all makes sense when you consider that the chance of survival is least with a long defended track. (I’m not counting the low-level mining trips to the Baltic and the Gironde estuary—but they often had some pretty tracer stuff defending them and there were losses even from those sorties.)

Life was not all flying and operations. We were granted a week’s leave every six weeks which I believe was unique amongst all the Services—Harris insisted on it. On base, in the Mess on evenings without flying, an extremely casual and happy-go-lucky atmosphere pervaded, particularly since Chedburgh was a temporary, war-time only, station with semi-circular corrugated iron Nissen huts for all offices and accommodation. There were favourite pubs in Bury St Edmunds, to which one or other of our broken-down jalopies would carry us; one of the pubs looked exactly like the studio version in The Way to the Stars.

There were frequent losses: faces would come and go only too quickly, but there was little point in dwelling on that. We young men wouldn’t wonder until we were some years older what the resulting sad administration was doing to our kindly “uncle”, the Squadron Adjutant George Wright. It was he who would be charged with informing relatives, dealing with personal effects, and clearing rooms ready for later arrivals. The Chairman of the 214 Squadron Reunion Association, Jack Dixon, has reminded me more than 50 years later that his crew and John Verrall’s were the only two crews to survive the whole period March to September of 1943. [Later statistics would show that 600 Stirling bombers were lost out of 1,750 built; 62 were lost in our last month—August 1943—alone.]

On 1st September our crew were told by George Wright that we had finished our tour. I was still 21 years old and the other five were about the same. John Verrall got drunk for the very first time since I had met him back at Westcott. We said farewell to our comrades and to a newly arrived CO, a Canadian Wing Commander Desmond McGlinn. Then we all went our different ways. I was posted to HQ No 3 Group at Exning near Newmarket to carry out analysis of operational logs and charts with a view to recommending how best to achieve maximum concentration of effort. It was always the stragglers—the ones who had been using inaccurate winds—who bought it from fighter attack. Generally speaking, the more concentrated the bomber stream, the less losses. During the course of 1943, it became normal practice to signal back calculated wind speeds and directions in order to harmonise that all-important factor.

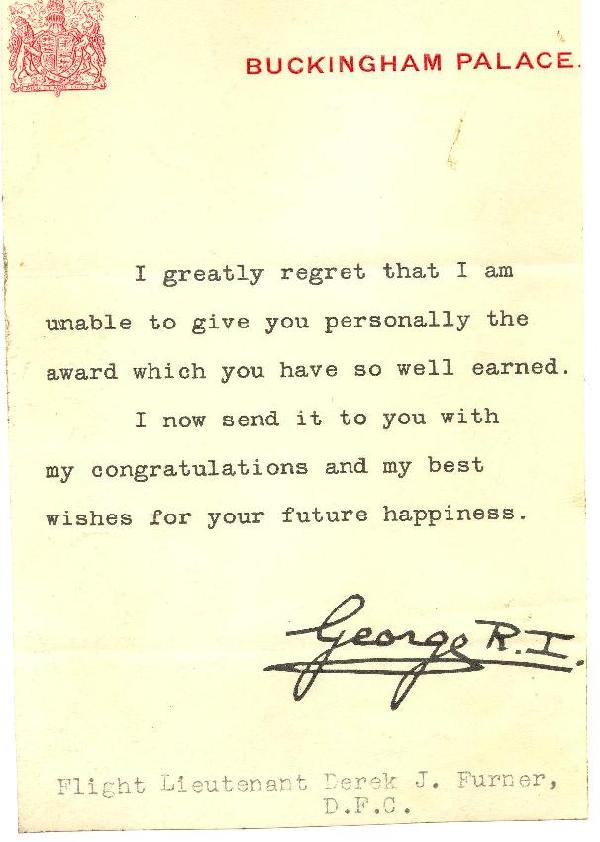

In November that year, I learnt that both Johnny Verrall and I had been awarded DFCs. They were sent through the post with a nice little note from George VI:

“Buckingham Palace. I greatly regret that I am unable to give you personally the award which you have so well earned. I now send it to you with my congratulations and my best wishes for your future happiness. George RI.”

***

Whilst I was at Exning, in November 1943, a new Group was formed in Bomber Command. It was known as No 100 Group with its Headquarters at Bylaugh Hall near East Dereham. The Group’s task was to bring together various squadrons and units, some existing, others still to be formed, that were to fight a secret war of electronics and radar countermeasures, attempting to reduce the losses of the heavy bombers and their crews. My old Squadron was to change its role and its aircraft.

It was just about Christmas 1943 when I heard of the re-equipping of No 214 Squadron with B17s (popularly known as Flying Fortresses), as part of this special force, and I had heard also that they were seeking a Navigation Leader (as Flt Lt). I couldn’t resist the urge to fly this new beast. American comfort—with ashtrays! I asked to see 3 Group’s AOC—AVM R Harrison. I told him that I would like to get back on the Squadron: he agreed. So I gave up the paper work at Group and hied off at the turn of the year to Sculthorpe, an American base where No 214, still under the command of Wg Cdr McGlinn, was preparing to accept the B17s after modification to RAF standards and the installation of a mass of Electronic Counter Measure (ECM) equipment.

The early months of 1944 at Sculthorpe were devoted to familiarising ourselves with the B17s and getting them installed and modified, much of the work being done at Prestwick by Scottish Aviation. The B17s were being fitted with a long list of intriguing pieces of kit—names like Jostle, Mandrel, Airborne Cigar, Airborne Grocer, Piperack and Carpet—each designed to jam a specific type of equipment or specific part of the transmission spectrum. German speaking operators were to be carried in the body of the aircraft whose purpose was to detect discrete R/T frequencies being used by fighters and ground control and jam them. In addition, RAF navigational equipment (Gee, H2S, etc) had to be installed to complement the US navigational kit of LORAN, a box similar to Gee but with LOnger RANge.

The Squadron was ready to operate in April 1944. Sculthorpe was to be a temporary home, reverting to American use on our departure in May to a neighbouring airfield at Oulton. That move was to be most significant in my life—bringing about a certain encounter—but more on that later.

The Squadron’s task was to provide electronic coverage to the main bomber force by jamming as many frequencies and equipments as our installed kit and the expertise of the operators we carried would allow. The main point of the B17 was that it had the height—say, 25000 feet—to fly a clear 5000 feet above our main bomber stream and thus provide jamming cover in all frequencies. We were inextricably linked to the bomber force and we therefore followed their route, with one or two exceptions when we were sent off to create confusion and deception on our own, for instance on the night of 5/6 June 1944. My task as Nav Leader, once the Squadron had settled down to its new operational role, was to oversee and monitor the efforts of all Squadron navigators and to act as the Squadron Commander’s (ie McGlinn’s) navigator on the operations he chose to take part in.

I flew on those B17s, mainly with Wg Cdr McGlinn but also from time to time with other captains, between January and August 1944, with operational flights from April. The number of flights recorded in my log book is 53, including only 8 operational flights. The latter were: Dusseldorf 22/4; Louvain 12/5; Antwerp 29/5; Eve of D-Day 5/6; Atlantic patrol 30/6; Villeneuve St Georges 4/7; North Sea patrol 12/7; and Wanne-Eickel 25/7. Each of the operations was precisely the same from the navigational point of view as those in my first tour. Accurate navigation was of the essence in order to afford the main stream the ECM cover planned for them; that meant accurate timing around each route as well as maintaining planned track. Other crew members had their own tasks—mine was the safe and accurate navigation of the aircraft, in itself a full-time job in those days of fairly rudimentary nav aids. The crew comprised a very experienced bunch of people: Captain and first pilot—Wg Cdr McGlinn; Engineer—Flt Lt Gunton; Signaller—Flt Lt Doy (still in touch); Gunner—Flt Lt Sharp; and two or three German speaking operators. The differences from the first tour were much increased height, and therefore more careful attention to oxygen mask fitting; somewhat greater comfort and less engine noise.

Most of us had graduated from the bombing role and it was an intriguing challenge to be protectors of those who were now continuing the bombing in ever-increasing severity. We were all mindful that what we were doing represented a vastly superior scientific and technological effort which was bound to contribute, sooner or later, to finishing the war. Our participation in the special screen set up on the night of 5/6 June 1944 served better than any other single event to confirm that idea in our minds. I quote from official reports: “On 5/6 June a Mandrel screen was formed to cover the approach of the Normandy invasion fleet, and from subsequent information received, it appeared that considerable confusion was caused to the German early warning system. Five Fortresses of 214 Squadron flown by W/C McGlinn [my captain], S/L Day, S/L Jefferies, F/L Peden [now QC, happily in touch] & F/O Lye, also operated in support of the D-Day operation in their Airborne Cigar role..an Me 410 had the misfortune to choose McGlinn’s aircraft which had F/L Eric Phillips, the Squadron Gunnery Leader, manning the tail turret, and he shot it down …”

The importance of that operation was brought home to me again in a most bizarre fashion many years later.

***

Let me interrupt this story of operational matters with a personal note. On 16th May 1944 we all flew in from Sculthorpe to Oulton, a few miles outside Aylsham. On the very evening of that day, some of us drove into Aylsham to survey the local pubs, and after a few beers I wandered across to the blacked-out Town Hall to look in on a dance being held there. Without hesitation I made a bee-line towards a lovely girl dressed in a pink V-neck dress standing across the floor from me. I had known girls at each place before, but there was always the acknowledgement that there would be nothing permanent about a relationship. I somehow knew this might be different. Her name was Patricia; she was 19, just a month away from her 20th birthday; she had a divine figure; she had a pretty face; she was an excellent dancer, easily able to follow my somewhat jerky steps (I whispered two lines in Spanish of Besame Mucho as we danced); she loved classical music and played the piano, with a distinguished pass in Grade 8 behind her. She lived in the town Square, just a few yards from the Town Hall. She told me some time later that her mother had almost dissuaded her from coming over to the dance that evening (you’re out too often my girl): when her father heard us talking below her rooms in Aylsham Square, I understand he said to her mother “It’s all right, they’re talking about Beethoven”. Patricia has been my wife for 55 years and is still as lovely as ever. More later on when and how it came about.

My flying was interrupted in September 1944 by a stupid accident. I should first explain that Oulton was one of the many temporary stations in Bomber Command—no permanent buildings, no fancy messes or barrack blocks. Most of the officers were billetted in Blickling Hall, previously owned by Lord Lothian who had been Ambassador in Washington 1939-40; and renowned for its historical association with Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. I used to run Music Club meetings in one of the ground floor panelled rooms of the Hall. A number of airmen and airwomen attended to hear me talk to a programme of 78s played on a wind-up gramophone with a sharpener at the ready for the fibre needles. In the grounds of the Hall, many temporary Nissen huts had been constructed, including one acting as the Officers’ Mess. One boozy night in that Mess, there was a sudden decision by everybody there to plant somebody’s footprints around the semi-circular ceiling of the Nissen hut—merely to convince gullible visitors that somebody had taken a running jump to do it. Well, it was decided that I was Joe, being fairly light in weight. A sort of scaffolding of tables and chairs was constructed, gradually rising in height towards the centre. I took off my shoes and socks, somebody else blacked the soles with shoe polish (yes, I know, it’s crazy) and I was carefully lifted up and had my feet planted on the ceiling one at a time. All was going well until we reached the highest point in the centre. The scaffolding began to falter, the structure collapsed, I fell from a great height and my right palm came down, unfortunately, on to a piece of broken glass on the floor. I don’t remember much of what followed but I’ve learnt since that the Doc (Vyse) was on hand and took charge. I was losing blood at a fairly fearsome rate to start with apparently, until he staunched it. I was carried by ambulance to the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital and was wrapped in a plaster cast for some time. The end result was the cutting of a tendon, a messy right palm and a permanently bent first finger. On the social side, I continued to see more and more of my lovely Patricia; but I must have knocked myself out of the operational business because I have no flights in my log book for the rest of the year. There was an amusing corollary to the foot-prints incident: at home on leave in Southend, I’d be showing my messy right palm to relations and friends and explaining frankly how it had happened; somebody whispered to my mother that I was almost certainly concealing the real facts and that it was a war wound.

***

In late 1944 my time in Bomber Command was about to come to an end. Unbeknown to me at the time, I was to return many years later, but one had no thoughts for the future in those days. There was only the present: the future did not yet exist. As I leave behind me the memories of the wartime Bomber Command which had been my experience for two years, there are two very serious matters which I must deal with. The first concerns survival. It is now well documented that Bomber Command suffered terrible losses. A total of 125,000 aircrew passed through Bomber Command in World War II. Of that figure, 75,000 (60%) were casualties—that is, killed, injured and prisoners of war. Those who died totalled 55,000 and they were all officers or senior NCOs. This was an appalling figure, unmatched even in the horrors of WWI. There is a very diligent researcher by the name of W R Chorley who has assembled books of Bomber Command aircrew losses for each of the war years. I have on my shelves the two books for 1943 and 1944: together they total about 1,000 pages. Every line in each book has a name—a Bomber Command aircrew loss.

I have already mentioned that I learnt from a pilot at a recent reunion of No 214 Sqdn that his crew and Verrall’s crew (mine) were the only two to get through the period April to September 1943 unscathed. You may ask—didn’t you realise that at the time. No, we didn’t. It was wise not to think too much about lockers and rooms being cleared out and how the Adjutant was writing letters to next of kin. So—what I am coming to is that I was very fortunate to have crewed up with Johnny Verrall. He was a tall laconic New Zealander and like the rest of the crew, in his early 20s: dedicated and reliable. Crew discipline and meticulous planning were his watchwords. Regardless of expected fighter strength, he would always insist that I announce the crossing of the fighter belt: he would corkscrew vigorously throughout the width of the belt, regardless of sightings. I am quite convinced that this tactic, more than any other, got us through the Stirling tour. He was adamant about chit-chat on the intercom, immediately stifling any trivialities. He did the most remarkable things with the Stirling when caught in searchlights—I once looked out from my curtains and saw the source of a light ABOVE us. He touched not one drop of alcohol through the tour: when our tour-end was announced he made up for it all in one night. If he hadn’t been as prudent as he was, we might well have joined the dismal statistics.

Mentioning a look-out from behind curtains prompts me to add that the navigator had an important advantage over many of the other members of the crew. The pilot, the bombaimer, the gunners, were all peering into the dark and from time to time seeing our own people go down. The navigator was busy most of the time, thrashing figures around, writing up a log, his constant concern being where am I, where am I going next and when am I going to get there. Not for him, for instance, the stark loneliness of squatting in a freezing turret searching the darkness for God knows what.

The Stirling came to the end of its bombing role soon after we had finished our tour. The losses were proportionately higher than those of the Halifax and the Lancaster, mainly because of its height performance. At the end of 1943 it was switched in role to the pulling of gliders in readiness for D-Day and subsequent forward pushes such as Arnhem.

Finally, there’s the subject of the effects of what we were doing. In the 50 odd years since those terrible happenings there has been a lot of heart-searching about the morality of Bomber Command operations—even assuming that it is sensible to judge events of one era aginst the morality yardsticks of another. I felt no guilt at the time—and I feel none now. It had all started at Guernica, carried on through Rotterdam, London, Coventry, Belgrade and countless other cities. To “Coventrate” even became a new verb. We were giving him his own medicine and that inevitably involved killing some civilians. But much more important were the military results: we were destroying armament manufacturing capacity; we were destroying missile sites, submarines and shipping; we were tying down millions of manpower in defences set up solely to counter us—searchlights, flak batteries, fighter squadrons, control centres; we were so weakening the offensive capability of the Luftwaffe as to ensure success at D-Day and after. Bomber Command operated for 1,400 nights, sending out 400,000 sorties; and from the middle of the war, the USAAF increasingly built up bomber effort by day. Harris was wrong in thinking that air power alone would win the war, but I am quite convinced in my own mind that, without the combined bomber effort over all the previous years, D-Day on 6th June 1944 would have been a failure and that failure would have changed history. Leonard Cheshire has put it very elegantly: “I am convinced that without the bomber offensive as he (Harris) ran it we would not have prised Fortress Europe open enough to let the armies in.” But the last word on the subject should go to Albert Speer, Hitler’s Minister for industry and armaments throughout the war. In his autobiography (1976) he wrote: “In my opinion the bombing campaign was the greatest lost battle on the German side.” He should know.

There was also the byproduct of domestic morale. I have front pages of The Times relating to all my operations and there is no regret showing in any of those headlines and those columns: indeed, they served in no small measure to bolster morale at home, particularly in the British cities which had been so grievously hit. From the start of the war until late 1944, there was little other evidence that the nation that had started it all was suffering.

There was another enemy—much further to the east. For me, in late 1944, the powers that be had other plans. It was thus a case of farewell to Patricia and keep in touch by letter for nearly three years.