The reason for the strange double name of the title will soon become apparent once we get to Scampton. But first there was the Vulcan refresher course at Finningley which now housed No 230 OCU as well as various other courses, for instance for Air Electronics Officers. The OCU had started life at Waddington back in 1957 when I had been Wg Cdr Ops. I had to leave the family at Finucane Rise whilst living at Finningley for just over two weeks in December 1967. Apart from classroom lectures, I flew six times, sometimes as a Nav Plotter, others as Nav/Radar. It didn’t take long to get back in the swing; but it was wise to refresh – I hadn’t flown at all for five and a half years. The people at Scampton waiting for their new CO had every right to expect him to be up-to-date on the aircraft. During those two weeks at Finningley, there were two outside influences which had a direct bearing on my new appointment.

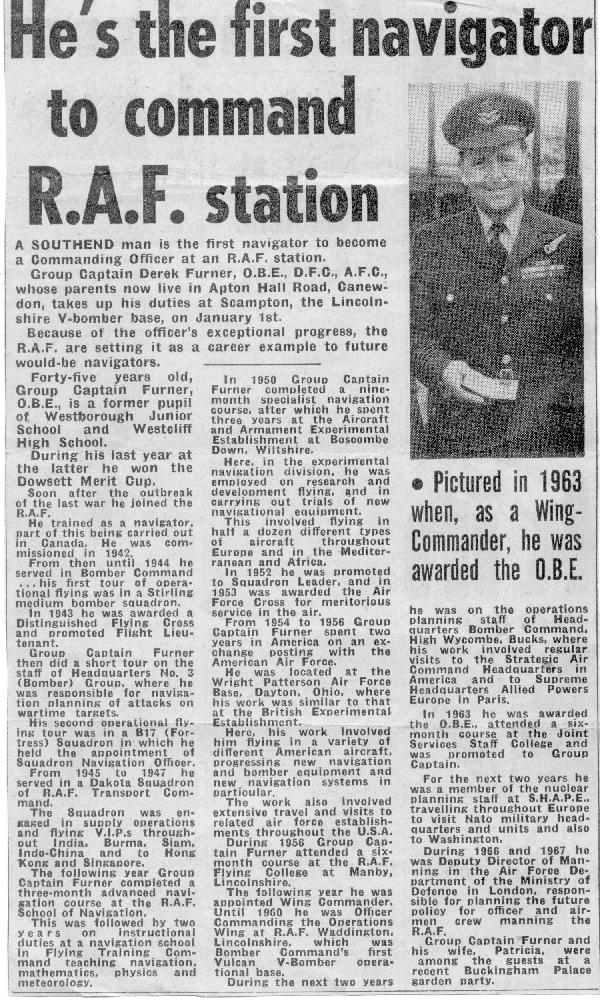

The first was a visit by a young Flying Officer from Scampton. Fg Off Chris Reid, it turned out, was Editor of the Scampton monthly magazine called “Delta” and he came to see me in the middle of the Vulcan refresher to write up an article about the new CO for the January 1968 issue. My immediate thought was “hey, watch it” and I chose my words carefully. (By the time I was settled in at Scampton I had learnt that “Delta” did need watching, too.) Anyway, there was a photograph and a page under the heading “Our New CO – What is he like?” Most of it was an accurate career history, but I was particularly pleased by the way he wrote this paragraph:“Much has been made in the press of the fact that Group Captain Furner is the first Navigator to be given command of a V-Force Station, so naturally I asked him about his views on this subject. He replied quite strongly that he didn’t like being spot-lighted in this way. As far as he was concerned the command of RAF Scampton was a GD Officer’s job and he was a GD Officer, it was as simple as that. In conclusion he told me that he was extremely proud to be associated with a Station as famous as Scampton and with the three equally famous Squadrons based there.”

I draw attention to the Navigator business because I haven’t seen the need to say much about it so far. Looking way back in time, there were few if any commissioned navigators before the war. They were looked upon as rather inferior beings to the pilots. WWII changed all that. It soon became clear that the crews of Bomber, Transport and Coastal Commands had to contain professionally trained navigators and as the war progressed many of them were commissioned – indeed, in their thousands. You have seen in Chapter 3 that it was taking just as long to train a navigator as a pilot. After the war, it was inevitable that some of those navigators were to prove sound enough to warrant higher and higher rank. It must be said that this state of affairs disturbed some of the old guard fighter types who had flown single seaters all their lives and, perhaps understandably, could see no need to spread the airborne tasks to other categories, and “Heavens, look at them – they’re wearing only half a wing!”. But the RAF that I know has always been a meritocracy and promotion has come to those who have worked hard, have proved their leadership qualities and deserve the challenge of greater responsibility. If a navigator met those criteria, then promotion would be accepted by all except a few bigots. Indeed, a few pilots, and a few navigators, carry on as if there’s a constant war between them: I had always steadfastly avoided confrontation of that sort. So – despite pride at having been given the task of commanding Scampton, I was pleased with the way young Reid interpreted my words.I have kept all the “Delta”s of my time at Scampton (ie the Station magazine). They are innovative, provocative and fun. I made use of it when I needed to. Where a straight excerpt will help, I’ll reproduce in quotes.

The second outside influence whilst at Finningley I’d like to record was an invitation from the Commander-in-Chief at Bomber Command HQ to have lunch with him. He was Air Chief Marshal Sir Wallace Kyle and I hadn’t met him before. The logistics were as follows: I would be flown to Booker, near High Wycombe, in a Basset; Pat would make her way to High Wycombe by bus (!) from the Quarter at Bushey Heath. All went well and we both arrived at Sir Wallace’s quarters around about the same time. There were about 10 of us in total around the lunch table. I was immediately to the right of Lady Kyle, who was seated at one end of the table. Pat was to the right of Sir Wallace, who was at the other end. To Pat’s right was Maurice Hermiston, also now a Group Captain on the Eng Staff whom we had known at Waddington some 10 years earlier. Now, the problem was this: Pat was completely deaf in the left ear – she had had a fall down some stairs when she was only three years old and had suffered a mastoid in that ear. Hence conversation was difficult for her from the left. Add in certain esoteric conversational material and there was scope for confusion.

At one point, Sir Wallace asked Pat what she thought of the Basset. He assumed that she had travelled down with me in the aircraft from Finningley. All Pat actually heard was the word “Basset”. “Oh no”, she said, “we don’t have a dog.” Hermy to her right whispered into her good ear “He’s talking about an aircraft.” Sir then tried again with a reference to a “good machine” (still on the aircraft). Pat heard “machine” and attempted to say something sensible about sewing machines. Sir, not to be outdone, persevered: “Ah, I see, you didn’t fly down from Finningley?” “Oh no, Sir Wallace, I came on a bus from Bushey!” Anyway, it was a good lunch, and a few months later, at Scampton on a most important occasion, which we shall come to later, he was extremely kind to Pat.

Business was discussed after the lunch. Sir Wallace was concerned about morale in the Command. Ironically, the results of my labours, and others’, in the Ministry were now filtering down the chain of command. There were lengthy signals about to arrive on every station spelling out the details of a pretty horrendous redundancy programme which was about to be implemented in order to meet the defence cuts that the Government was making. Sir Wallace was anxious to stress to me how vital it was to put all this over in the best possible light and to highlight the fact that the V-Force still bore the responsibility of representing the British nuclear deterrent force. He also gave me four month’s notice of a most significant event on 29th April which I would have to organise. The discussion gave me much food for thought. On the flight back to Finningley I began drafting the bones of a speech to Scampton personnel.

I took over command of Scampton early in the new year, 1968. I kept discreetly out of the way when the Officers saw my predecessor – Gp Capt Alan Mawer – off the Station. He had left it in good order.

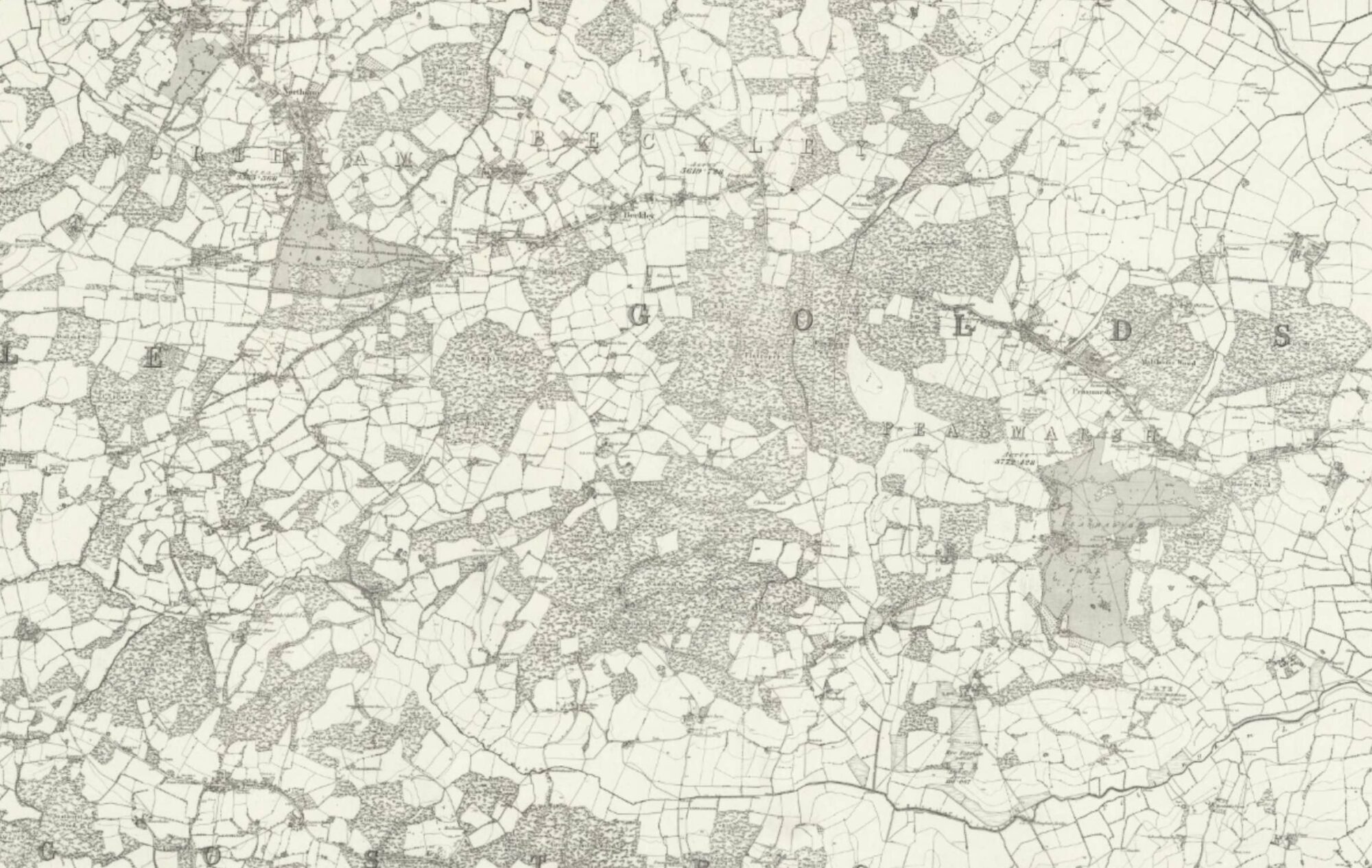

Before I go any further, let’s be clear on the chain of command. Under HQ Bomber Command there were now three Group HQs – Nos 1 and 3, plus a small one at Central Reconnaissance Establishment (CRE). (I didn’t know it at the time but it would not be long before I was to know CRE at close hand.) No 1 Group controlled the Vulcans and No 3 the Victors. Within No 1 Group the Stations were: Coningsby, Cottesmore, Finningley, Scampton and Waddington.

Scampton in January 1968 was equipped with 3 Squadrons of Vulcan Mk 2, that is, 24 Vulcans in all, each carrying the Blue Steel “stand-off” missile which could be programmed to hurl a nuclear weapon 100 miles from launch. The Squadrons were No 27, whose emblem was an elephant – remember that! – No 83 of which I had been an honorary member at Waddington, and No 617 of Dambuster fame. The total of RAF personnel on the Station was 2,000; there were also 250 civilians; with families, the station became a small town of 6,000, living in 1,100 married quarters; the Station participated in 30 different sports. Of that town, I was to be Mayor, Chief of Police, Judge, the lot, a responsibility not to be taken lightly. How do you supervise the efforts of 2,000 individuals? The short answer is – you can’t. What you can do, and must do, is create a climate in which everybody is eager to complete their own task without error.

My first task, however, was the unpleasant one of telling the station about the redundancy programme. I could have announced the thing on the Tannoy, a Station-wide system of speakers which broadcast from a microphone in the Operations Centre, a few doors down the corridor from my office. But the situation demanded a more personal touch, and I wanted everybody to see me – for the first time. I asked Wg Cdr Admin to make sure that all personnel except those on essential duty were assembled in one of the hangars at a certain time; I asked Wg Cdr Eng to arrange for me to be hoisted on one of those high level work platforms beside the cockpit of a Vulcan, so that I was visible to everybody there. This is what I said.

“Royal Air Force Scampton: since I have been here no more than a few days I welcome this opportunity to talk to you all together. Some of you I’ve already met at close quarters and I shall meet more of you as time passes. Apart from introducing myself to you, I have to read something to you. (Flourish two yards of telex on pink paper, read details of RAF cuts and consequent redundancy plan. At the end, fling the paper down to the floor of the hoist.)

So much for the official words. Now a few of my own. Decisions come and go; policies come and go. The question is – “How are we here today affected?” and the answer is – “Very little” – because we at Scampton have a job to do, a big job, an important job, and we shall continue with that job for some time to come. We’re a darn busy station and we shall stay busy. And that goes for all of us – those who fly aircraft, those who equip and service aircraft, those who feed, house and pay all of us. But none of you is an automaton. You are all thinking people, and I’m sure many of you are thinking seriously about the future of the Royal Air Force. The news of that future may look a bit bleak as a result of that telex I’ve read to you, but let’s get it into perspective. We already knew we were pulling out of the Far East – it has merely come forward a few years. We already knew we were dropping our front line from over 800 aircraft today to something under 600 in the future. Even now, with the F111 cancellation, it is still planned to level off at somewhere between 500 and 600.

Redundancy? – that dreaded word. They’ve just completed the officer part of Phase 1 involving a few hundred officers without a ripple as far as any individual station is concerned, and they’re still proceeding with the current phase for airmen, involving 1% of the total. Two months ago when I left MOD there were planned to be other fairly small numbers to follow in the years 1969 – 1971. The earlier FEAF withdrawal will probably increase that figure a bit. Yet, even so, this will affect only a few % – say 3-5% – of the total and will almost certainly be on a voluntary basis as far as it can possibly be done.

The RAF’s total strength today, all ranks, is 115,000. Even after the politicians have done their worst, we shall not be lower than about 85,000. [2000 observation: now 50,000 and still falling.] But the large bulk of that reduction will be achieved by natural wastage and normal retirements. After all, fifteen years ago we were at a figure roughly double today’s 100-odd thousand.

But enough of figures: the point I have to stress to you is that we have a job to do. The nuclear deterrent role is an awesome and vital one. We form at Scampton a major part of one of the most sophisticated and efficient forces in the world. Nobody has taken that away from us in these announcements.

In 1968 at Scampton:

We have flying tasks and readiness tasks to meet;

We have training requirements to fulfil;

We have weapon loading times to win in rivalry and competition;

We have bombing competition results to humble every other Bomber Command Squadron with;

We have sports teams to lick everybody and his brother with;

We have photo competitions and catering competitions and handicraft competitions and Police dog competitions to beat other stations in – and a lot of others besides – the list of challenges is endless.

This is what Scampton’s life is all about. Scampton – the biggest station in Bomber Command, the station with more flying machines than anywhere else and the station you have made the best. And in particular in 1968: we shall mark in many ways the 50th Anniversary of the Royal Air Force; we shall participate, without falldown, in the Queen’s Flypast and Review in June; and on the 29th April it falls to Scampton’s honour to mark the transition from Bomber Command to Strike Command, a duty we shall carry out with pride and efficiency.

So no Moaning Minnies! We haven’t time to worry about the politicians [wave the pink paper again] and their problems. We have a big job to do!”

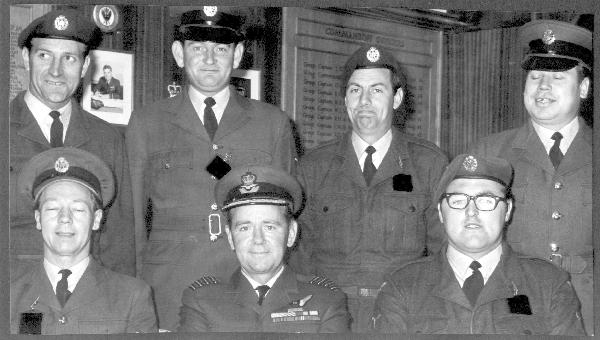

I have chosen to reproduce my first words at Scampton in full for they serve to summarise what the Station was about. My Wing Commanders and I would meet at 8.30 am every morning in my office to plot the day and to discuss any special problems. I enjoyed an excellent team: there were six of them – firstly the three Squadron Commanders, John Pack of 83, large as life and extrovert, Bob Allen of 617, quieter but very efficient, Phil Goodall of 27, an effective commander but just a bit prissy with it; then the three “Station” Wg Cdrs, John Deards, Operations, solid and dependable, Alec Roke, Engineering, a tower of strength with a helluva job maintaining both Vulcans and Blue Steels, and finally, Jack Gilvey, Administration, who was destined enthusiastically to burn much midnight oil with me concerning the day to come on 29th April.

It was with Jack Gilvey that I would inspect some part of the Station every Wednesday morning, bags of bull, and meet people in their own working environment; we would plan to cover the whole Station over a period of about three months – everything, work places, weapon housing, living quarters, Messes, Clubs, outstations (Faldingworth and Hemswell). Occasionally – not often – Gilvey would bring before me an airman who had transgressed in some minor way. This would involve an “Orderly Room” in which I would wear my “Judge’s” cap, listen to the evidence, decide whether the charge was substantiated, explain to the unfortunate chap why a punishment was necessary, and usually finish up by awarding a reprimand. Always, after the formalities, I would remove my cap, ask for the airman to come back in, on his own and also without cap, and we’d have a chat. I can’t remember seeing the same face twice.

One of the “special problems” we discussed at my early morning prayers with the Wing Commanders – well, it wasn’t a problem, rather a project – was a plan announced by the Daily Mail to organise in May 1969 a Transatlantic Air Race. HQ Command was seeking ideas. The object of the race was to time every entrant from the top of the London Telecom Tower to the top of the Empire State Building in New York City, or vice versa. Any means of flying could be used, whether civilian or military. As a result of our discussions one morning, I sent off a plan devised mainly by John Pack: helicopter to the nearest airfield suitable for a Vulcan; parachute drop from the Vulcan over one of the two NYC rivers; pick up by launch; motorbike to the bottom of the Empire State. It was a great idea and we were all very enthusiastic about it, but it didn’t feature in the final RAF entries. What I didn’t know at the time was that I’d be somewhere else in May 1969 and have a direct interest in the race.

I must interrupt the business of running Scampton with a word about the family. Pat had joined me from Bushey Heath early in January and we were able to set up home once more in (Home No 21) No 1 Trenchard Square (every permanent station had a “Trenchard Square”). Around the rest of the Square were four of the six Wing Commanders. No 1 seemed huge compared with previous homes but, of course, it was an ideal place in which to entertain. As to the boys, Peter was at Brunel University, Richard had returned for the new term to Stamford, now much closer again, and Jonathan, at exactly one year old on the day I was talking to the Station for the first time, had been looked after in Norwich with Pat’s parents for a short time until we had really settled in the Quarter. The AOC at No 1 Group, our immediate HQ, was AVM Mike LeBas, a delightful man whom I had first met at High Wycombe some years before. His wife was Moira and she had a very friendly talk with Pat, pointing out that having a very young child as a CO’s wife was really a God-send: use him as an excuse not to get too tied up in rituals such as the Wives Club. This was excellent advice: Pat delegated the Chair of the Wives Club to Jill Gilvey who was only too happy to take it on.

Jonathan at Scampton had a couple of nasty events: on one occasion our batman poured out for him a supposed lemonade from a bottle containing neat gin; needless to say, this didn’t go down well with a one-year old. On another, he stumbled into an old wartime air-raid shelter in the garden and disturbed a whole nest of wasps; they all attacked his head. Only immediate attention from the Station Medical Officer (Josh Mitchell) averted a tragic outcome.

Despite the successful transfer of responsibility for the running of the Wives Club, the social life was still extremely hectic for Pat. We entertained frequently in the Quarter; we had a fair number of official visitors whom we hosted for the night – the local Bishop, the Moderator of the Church of Scotland (who was very fussy about the silk bits of his dress), and an ex-CAS, Marshal of the RAF Sir Dermot Boyle. She attended many Guest Nights in the Mess, the annual Scampton Ball and Balls at No 1 Group and neighbouring Stations, events for the local citizenry, sessions with the local TV, and so on. One of the funnier occasions with the TV occurred when I was asked to be one of the judges for the Miss Anglia contest; the TV Weather man was another. We had a very complicated form put in front of us to mark contestants out of 9 against several appropriate headings; but the TV producer put us at our ease by saying “Just give one figure, say 7, for the first contestant, and then go up or down from there, as the case may be, for the remainder.” Somehow we judges came to a consensus and the winner was crowned. I subsequently received a letter from the Publicity Executive of Anglia Television Ltd which included the remark “I assure you that although you and the other judges had a difficult task, you chose wisely”. That was nice to know, but one can’t help feeling sorry for the losers.

We entertained the Bishop of Grimsby to lunch one day. For obvious reasons, he was known locally as the “fishy bish”. He had a nice sense of humour. At one point, over coffee, I asked him just exactly what it was that he said to the actress. Quick as a flash he replied “What are you doing in the interval?” On another occasion we had a whole day for prominent locals, bigwigs, councillors, police – and elderly neighbours under or near the approach corridor; we called it “Neighbours’ Day”. It was a welcome opportunity to explain deterrence – and aircraft noise. By the way, reverting to clerical types, I remember the padre coming to see me in my office some time in the first week of my command: “Don’t hesitate to come and see me if you’re feeling the pressure of work and would like some sympathetic counselling”, he said to me. Some months later, he got himself into a ludicrous situation because some careless words of his about extra-marital relationships found their way into the local newspaper. As a result the roles he had envisaged were reversed and I had to give him some friendly advice.

I had to speak at most of the Guest Nights and Dining-in Nights and I kept a careful log of jokes used on each occasion. Then there were other special speaking occasions such as Burns Night, the 25th Anniversary of 617 Squadron, the commemoration of 83 Sqdn’s winning of 6 DFCs in one night – giving rise to the 6 points of the antler in their crest – and a night in which 27 Squadron invited an elephant into the Mess. All of these occasions demanded a bit more than the usual research. And I’m sure you want more information on that elephant. An elephant features in the crest of 27 Squadron. OC 27 decided to have a Guest day and night with a baby elephant invited, with its trainer, and previous commanders of the Squadron. Just prior to the dinner (sit down at 7.30 pm) officers of 617 Sqdn had hi-jacked the damn elephant and hidden it somewhere on the station. I got hot under the collar. I read the riot act at Bob Allen of 617 – “Get that animal back immediately otherwise I shall cancel the dinner.” The elephant reappeared smartly and the evening progressed as planned. The next morning somebody had dug a huge grave with a sign giving the elephant’s name alongside the smaller grave outside 617’s hangar built many years before for Guy Gibson’s dog. Incidentally, our own Jonathan was photographed on the front page of one of the tabloid newspapers gesturing towards the elephant.

I suppose the most famous visitor was Princess Margaret. She was opening something in Lincoln and she flew into Scampton in one of the aircraft of the Queen’s Flight. She was received on the airfield by the Lord Lieutenant of the County and myself. The ladies’ lavatory in the Mess had had a good going over to ensure that it met the highest standards. She was soon whisked off by an official car to the City of Lincoln. On her return later in the afternoon, I had to warn her that her take-off would have to be a bit earlier than planned because of the possibility of fog at Northolt. She hopped aboard her aircraft with alacrity and without fuss.

“Unveiled today at RAF Scampton, a new weapon system that Defence experts believe will carry the RAF well into the seventies. Intended for use in a wide variety of roles, Tactical Reconnaissance Interceptor Killer Equipment (TRIKE) has been evolved from a design study of maximum cost effectiveness ratios.” And so it went on for a couple of pages together with a photograph of five chaps in flying gear on a “Stop me and Buy one” tricycle.”

The more serious side of Scampton went on apace. Apart from the routine training flights in the UK, there were many overseas visits – “Rangers” they were called, including “Western Rangers” to Goose Bay in northeast Canada where low level flying could be rehearsed without bothering farmers. There were no-notice exercises where an international emergency would be assumed and we had to “generate” to full serviceability as many of the 24 aircraft as possible and as quickly as possible. There were invitations to perform in many different parts of the world, giving the RAF the opportunity to “show the flag” by displaying what was probably the most awesome looking aircraft in the world. There were rehearsals and the actual day for the Queen’s Flypast. And there was that special day which I can remember very clearly indeed: 29th April 1968. Let me deal with the last three in more detail.

The AOC and I took two Vulcans to the Toronto Airshow. He piloted one, and I navigated the other. The Canadians ensured that we all had a splendid time. We took part in several display days and the Vulcans were the hit of the show. Nothing was too much trouble for our hosts: we were supplied with a couple of Cadillacs to be mobile; parties were held all over the town; I met and befriended Johnny Fauquier who used to command 617 Squadron after Guy Gibson and he and I played a lot of argumentative bridge and drank a lot of whisky.“Foreword by Gp Capt D J Furner: This issue of Delta is different. The First of April 1968 is a big day in the history of the Royal Air Force. It is the RAF’s 50th Anniversary. It was on 1st April 1918, eight months before the end of the First World War, that the RAF was constituted as a separate fighting force and that the motto “Per Ardua ad Astra” was transferred from the Royal Flying Corps to the Royal Air Force…As you would expect with a total uniformed strength as large as 2,000, we reflect at Scampton a wide range of ages and lengths of service. We have young men under 20 with only a few months’ service and we have a few at the other end of the scale who are nearing retirement with some 38 years behind them – more than three quarters of those 50 years…You will see from this special Anniversary issue that we shall be playing a major part, later in the year, in HM the Queen’s Flypast at Abingdon… “

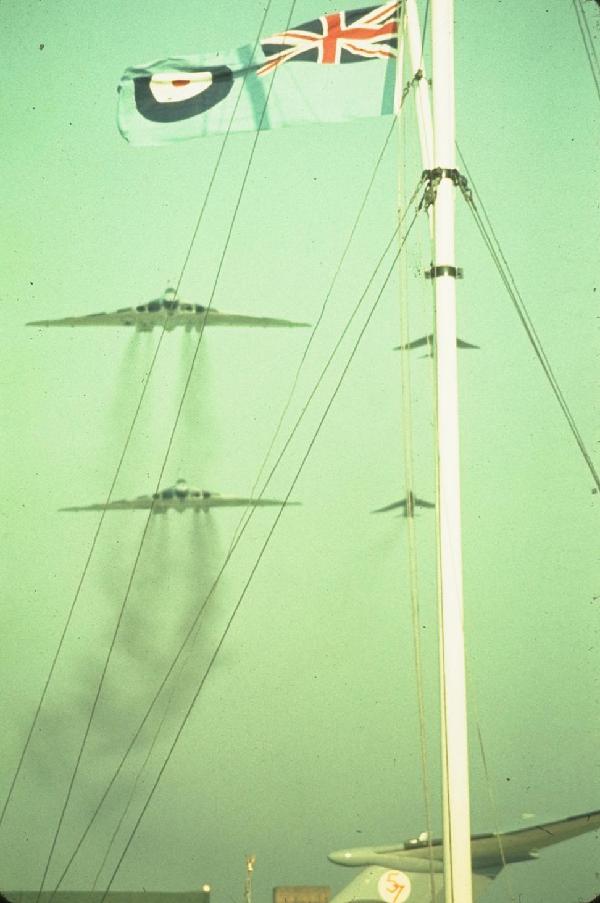

There were a number of rehearsals for that flypast. They were vitally necessary because the three Squadrons were to fly a small formation each with exactly the same distance between each formation. I can’t remember now what that distance was, but it was a fixed number of yards. I could foresee that wide deviations from that distance would make our part of the flypast look scruffy. I asked Alec Roke in his workshops to make us some simple sights with an eye ring, a length of metal and a bigger ring at the forward end, having a diameter exactly designed to equal the wingspan of a Vulcan ahead as it would look at the required distance. A group went out into the country at a spot under the rehearsal – the AOC, some of his Air Staff, and three Vulcan station commanders. As they flew over our heads it was obvious that three formations (I knew they were 27,83,617) were keeping to a tight required distance. Well, you can guess the rest. The other stations were instructed to liaise with our Wg Cdr Eng. I flew on the remaining rehearsals as nav/plotter and stood behind Bob Allen on the actual day. It went off beautifully.“The 50th Anniversary and the formation of Strike Command are not of course in any way connected, but it falls to Scampton’s honour on the 29th of April to mark the transition from Bomber Command to Strike Command – a duty we shall carry out with pride, with dignity and with efficiency…”

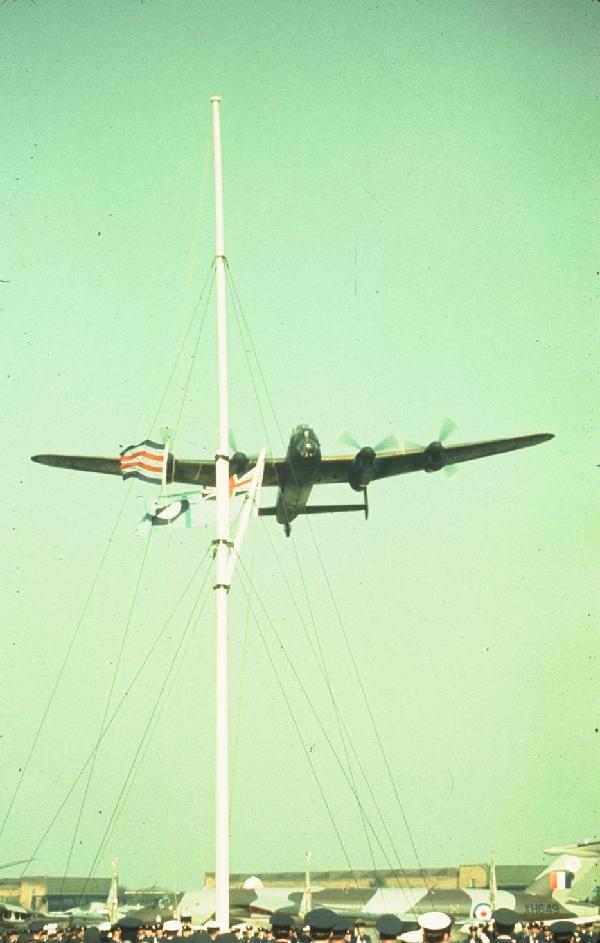

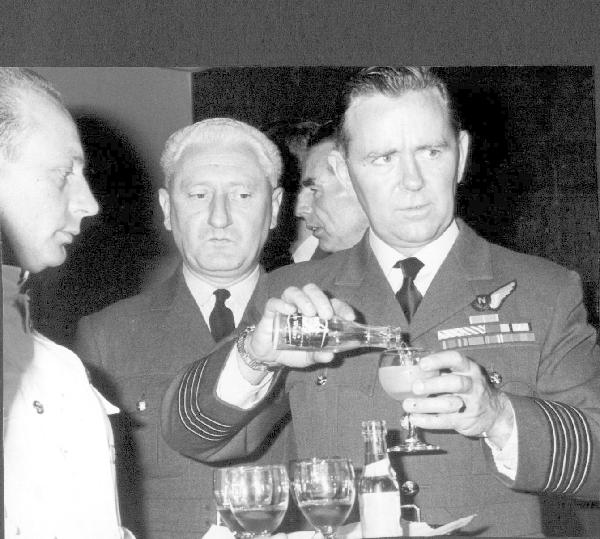

This was the event that the C-in-C had warned me to be ready for when I met him for lunch in December the previous year. It’s no exaggeration to say that work had to start on this event as soon as I got to Scampton. The event was to mark the joining of Fighter Command and Bomber Command into one – Strike Command. Fighter Command had had their ceremony previously; this was the Bomber event. It comprised the following: a luncheon for 200 guests headed by the Secretary of State; a flying display involving 15 separate items in 55 minutes; a ceremonial parade involving personnel from nine stations and fourteen squadrons (Furner as Parade Commander); overflights during the parade, timed to the second, of Lancasters and Vulcans; and a final reception for all the Guests in the Officers’ Mess. The guests were planned to arrive in many different ways and in many different aircraft; they all had to be met and treated as VVIPs or plain VIPs. Provision had to be made for bad weather (Plan B). Jack Gilvey had the heaviest task – producing a vast tome, the Administrative Order, which covered every possible detail of arrivals, reception, PA system, transport, press, families, Guard of Honour, catering, static aircraft, equipment display, dog display, photography, local interest, station cleanliness (rather like AOC’s inspection – “If it moves, etc…..”), escort officers, collection and identification of Air Marshals’ caps (oh, yes!); he was helped considerably and most sympathetically by AOA Bomber Command (at that time AVM Barraclough) and his staff. I tasked John Deards with the organisation of the flying display and John Pack with its commentary; Bob Allen with the four-Vulcan scramble (the opening highlight of the display); and Phil Goodall with masterminding the receiving and escorting of all the guests, employing all junior officers not otherwise engaged.

Denis Healey was our No 1 guest and he was accompanied by Merlyn Rees, his Under Secretary. The Chief of the Defence Staff came, Marshal Elworthy; Viscount Portal and Marshal Harris from WWII came; Barnes Wallis who invented the bouncing bomb for 617 Squadron in 1943, he came too; the C-in-C, Sir Wallace, was there of course, together with all his senior staff from High Wycombe. All living ex-Cs-in-C also attended, as did all ex-AOCs of the various Bomber Groups – 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and CRE – masses of current and ex-Bomber Station commanders, 15 Squadron Commanders, 3 Bomber Command VCs (including Cheshire), 7 Air Attaches, 11 Civic Officials representing 9 Counties. If you’re interested, the Air Ranks present (3 Marshals, 19 ACMs, 11 AMs, 31 AVMs and 20 Air Cdres) totalled 206 “stars”. In short, dear reader – make a go of it and you’ll be noticed; make a cock of it and you’re doomed.

In the event, it seemed to turn out all right. The Secretary of State was at his most jovial when I greeted him on the tarmac, all the high-powered people were shepherded correctly to the Mess, the luncheon table looked absolutely stunning, the C-in-C spoke, Healey spoke (very warmly about the V-Force) and I spoke – just to warn them that high-powered or not, they were going to be moved about that afternoon in buses, and to stick my neck out and forecast that the rain that had been falling would stop just before we went out for the flying display. (I had taken a quick look at the Met chart in the morning.) Not only did the rain stop, the clouds all cleared miraculously, the sun came out and Plan A was confirmed. Sometimes you win.

At the beginning of the flying display, there was the first – and only – glitch. Of the 4 Vulcans all sitting ready at the end of the runway, Bob Allen’s own aircraft, which should have been the first to go, could only get three engines to burn. A slight pause, then the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Vulcans moved out past him and got off in quick succession. It could have happened to anybody; but the AOC, Mike LeBas, was furious with poor old Bob; he thought he should have taken off on three engines. I’m quite sure that, after reflection, he would decide that he was wrong and Bob was right. It was so frustrating that the start of the whole thing didn’t go as planned. But all was forgotten as the display continued. Fast and furious came the other items – a Victor, a Victor tanker and a couple of Lightnings, 2 Vulcans, Canberra, Hart, Lancaster, Mosquito, Valiant, Spitfire and Hurricane, and the Red Arrows in their 9 Gnats. All in wall-to-wall blue sky.

Next came the ceremonial parade. On one of the minor runways, I had 9 stations in front of me: to my left, Finningley, Wyton and Marham; directly ahead Lindholme, Bassingbourn, Cottesmore, Scampton and the Band; to my right Waddington, Wittering and a WRAF flight. The C-in-C was to take the General Salute, flanked by Harris and Portal. At certain points in the ceremony, I was to order the Bomber Command pennant to be lowered, at which precise moment a Lancaster would fly over at very low level; and a minute later to order the raising of the Strike Command pennant, at which moment two Vulcans would overfly. There were two small problems with this. Synchronisation (I had my back to the incoming aircaft) and I had to know the time to the second. Solution – position an airman a few miles to the east of the airfield under the incoming route; radio link to the Tower; switch on bright light on top of a hangar in my view; wire in a watch to the inside guard of my ceremonial sword. It all worked. It’s not given to many of us to be in a position to give the order “Royal Air Force Bomber Command, General Salute, Present Arms”.

Then was the reception back in the Mess – with wives. In the course of chatting to as many Guests as I could, I remember talking at some length to Leonard Cheshire: he was full of admiration for the whole day and confessed that he would have been no good at “that sort of thing”. Well, it was different in those days, as many of us could remember. And this was the occasion when Sir Wallace was so kind and so understanding, talking to Pat and raising her morale no end by congratulating her on the support she obviously gave her husband; he appreciated under what pressure the wives also were on these occasions.

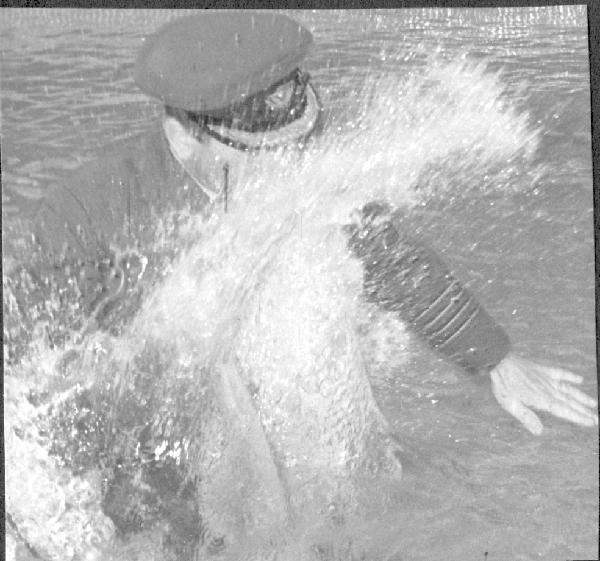

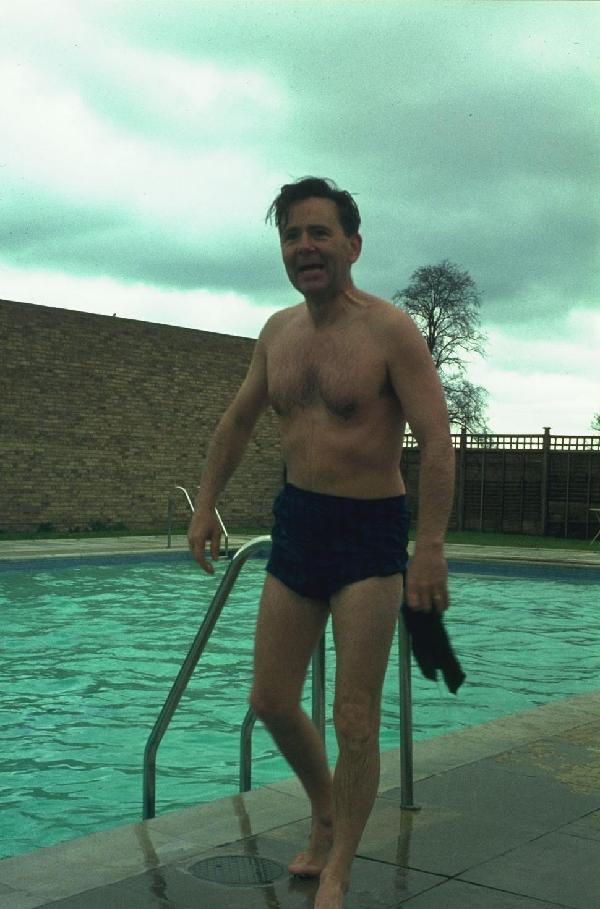

After the last Guest had left, I invited all the Wing Commanders and their wives to our quarter for lashings of champagne and nibbles. It was indeed an occasion for celebration. In the days that followed, telexes and letters literally poured in. The telex from the C-in-C read “Today’s ceremony was a great success and the direct result of careful planning, much hard work and in the acid test, excellent application. It showed the Royal Air Force proud of its past achievements but conscious of the need for efficiency in its daily task and flexibility about the future. Scampton took the brunt of this great effort today and I congratulate you and thank all ranks on the station. You can be well satisfied. Sir Arthur Harris has asked me to send his personal congratulations.”“The Station Commander has issued a challenge through the pages of Delta. He has walked right round the airfield peri-track in 53 minutes, an average speed of 4.6 mph. The only concession to comfort was the donning of a pair of rubber-soled shoes, ie he was in uniform plus cap. A point to remember before setting out, he doesn’t have the trouble with the airfield security flight that you might have…” “The Station Commander opened the pool by jumping in in full uniform and stripping it off bit by bit…For his efforts he gets one survival exercise and a wet dinghy drill to his six monthly training requirements.”

I also gave the Editor of Delta a number of mathematical puzzles and cross-figures during the year. One of the most complicated involving fourth powers with 15 digits each was finally solved and earned a promised £1, but the winner couldn’t explain how he started to solve it. Not to be outdone, Peter and Richard also provided cross-figures.

Alongside the highlights of the year 1968 were the routine matters: not least the Quick Reaction Alert, one aircraft at all times, ready loaded, crew beside on bunks in a hut, at 15 minutes readiness. This was still very much Cold War time. From time to time, I would leap up from my easy chair after dinner and drive out to have a chat with the crew for the day. And there were the more mundane events, but not less important in running the station: welcoming new airmen arrivals, explaining what Scampton was all about, visits to the Airmens’ Club and the Sergeants’ Mess, receiving visiting brass including the Chief of Staff of the Italian Air Force, vale to outgoing C-in-C, ave to incoming C-in-C (Spotswood), AOC’s inspection — “If it moves,…..”; and a very emotional farewell to AOC Mike LeBas who continued to be a good friend until, sadly, he died. And of course there was my own flying. I flew 26 times in the Vulcan that year with 14 different pilots, including the three Squadron Commanders, both as nav/plotter and nav/radar.

I haven’t mentioned holidays. In 1968 I’m afraid there wasn’t time for any.

Thus a year went by. Before the year was out, I was warned that we should get ready to pack our bags again. We were to leave Scampton immediately after Christmas. Down the A1 to Brampton, near Huntingdon.

I took the opportunity to place a record of the year in the next issue of Delta. It serves now to complete the picture of the year with anything I’ve forgotten in this Chapter.“The Editor has given me this opportunity to say farewell to you all through his columns and I cannot conceive any better theme than to stress, once again, the point I have made to you so often – SCAMPTON, you are the biggest and best in Strike Command. The size is, of course, a matter of fact; the quality, a matter more of subjective opinion, but look at the evidence in 1968. Your bomb-loading teams in March carried off the BS Trophy in the BC Bomb Loading Competition. You hosted hundreds of visitors on dozens of occasions – eg, from all the major courses in the country, the CAS of the Italian Air Force, our civilian neighbours in Lincolnshire, the Prices and Incomes Board and many others. You achieved a higher utilisation rate per available aircraft than any other MBF station. You achieved 95% of the AOC’s flying target throughout the year, and in October flew more hours than in any previous single month, and over the year flew more hours than in any other Blue Steel year. You were progressing at the time of writing towards a most satisfactory position in the No 1 Group Proficiency Trophies, and in the Bristol Siddeley Bombing Trophy competition, Scampton Squadrons filled the first three places. You mounted, on April 29th, with admirable dignity and efficiency, one of the most ambitious ceremonies ever held on one station in this Command. You participated time after time, without falldown, in rehearsals and actual display days for HM the Queen’s 50th Anniversary flypast. You exercised a number of times in generation, and on one occasion produced the fastest generation ever. You were Soccer champions for the RAF Senior Cup and the No 1 Group Cup. You were tennis champions, winning the RAF Challenge Cup and the No 1 Group Cup. Your golf players won the No 1 Group Inter-Station Handicap Trophy. Your squash players won the No 1 Group Cup. You won the final of the RAF Inter-Station Pistol Team Championships. You provided individual champions in angling, boxing, cycling and fencing. You reached the final of the No 1 Group Cricket Cup. You published 12 issues of one of the best station magazines in the RAF; DELTA won an award from the British Association of Industrial Editors. You provided a majority of the players in both the No 1 Group Brass Band and Pipe Band and participated in dozens of events, Service and civilian. And – like it or not – you paraded more times in one year than for many a year. You – SCAMPTON – all 2,000 of you – did all this. Those of you who fly, those of you who service the aircraft, weapons and equipment, those of you who feed and pay and clothe and minister to the needs of all, those of you who guard and control and standby and drive – all of you – did this. It has been a privilege and an exciting experience for me to command this Station over the past year. I am sure you will go on to even greater things under my successor and I take this opportunity to wish all of you here the best of good fortune in 1969.” As a result of Scampton’s efforts in 1968, No 1 Group awarded its Vulcan Efficiency Trophy, assessed on all major aspects of operations, training, engineering and administration, to RAF Scampton. It was formally presented to my successor, Gp Capt Terry Fennell, by the new AOC, AVM Wade, early in the New Year.

I was dined out of the Sergeants’ Mess and, of course, the Officers’ Mess. In my farewell to the officers I likened the role of the Station Commander to that of the conductor of an orchestra. He called upon each Wing to perform of their best: the Operations Wing were the strings, providing the main theme, a trifle shrilly at times, but confident in moving the performance forward; the Engineering Wing, the brass and timpani, loud and forthright; the Administrative Wing providing the somewhat plaintive notes of the woodwind sections. The tempo was generally allegro, seldom adagio, sometimes con fuoco. The conductor could not necessarily play all or even many of the instruments of the orchestra, but the important thing was that he had to keep them all together and KNOW THE SCORE.

I also, for the first time, mentioned my navigator category. To those who would argue that you needed a pilot to deal with a flying emergency situation, I would say – Why? In the Control Tower, in an emergency, I was surrounded by experts in every field, assisting me to make the right decision. There was even a positive advantage. I was able to fly as an active crew member with all three of the squadron commanders who happened to be pilots, and thus know them better.

Pat and I left Scampton one grey morning after being given a “ceremonial” tour of the station in a pony and trap, closely followed on foot by all the Wing Commanders and the new CO. Little did I know then that I would return to Scampton twice more – in 1981 for the 25th Anniversary of the Vulcan, and in 1995, sadly for Scampton’s closure.

Brampton in Huntingdonshire – as an Air Commodore – was our next stop.