I did a ‘recce’ of my own in Brussels. I went over for a day to see the Brigadier (in view of something that follows, I think perhaps I won’t mention his name), discuss the nature of the job and find out about his quarters. He was living in a hiring in the eastern suburbs, an Edwardian house with three floors and a basement, and I was able to confirm with its owner (a Belgian diplomat working in the UN in New York) that I should take it over from the Brigadier.

It was about the 17th of October that we packed and left Brampton. With no successor I had complete flexibility with 37 Park Lane. By this time we were running a second hand Jaguar Mk 10 and pulling a long Sprite Major caravan. One didn’t dwell on the total length. Both car and caravan were heavily loaded with all our wordly goods. The three of us and our cat stayed on a Dover caravan site overnight and the next morning we couldn’t find the cat anywhere. Jonathan was very dismayed, of course. We asked the site manager to watch out for it and we would come back to collect it. Then we crossed the channel to Ostend to begin my fourth overseas tour and Pat’s third. After disembarking, it was straight down the autoroute to Brussels, through the City (a surprisingly easy drive) and out on the elegant Avenue Tervuren through the district of Woluwe St Pierre. A turn off to the right and we were in our street – Avenue Colonel Daumerie – and I stopped opposite No 15. I remembered the layout of the house: I had to open a double gate before I could get the car and caravan through. It was raining – very hard. I parked, for a couple of minutes, on the opposite side of the road in order to give me the space needed to turn in. I ran across the road to open the gates. Before I could get back into the car, there was this Belge charging out of the house opposite, waving his umbrella about, telling me I couldn’t park outside his house. “Pas de probleme, monsieur” or some such, said I, and swung in to the now open gate with 12 yards of vehicles behind me. Our first welcome from Belgian neighbourliness. Anyway, he got wet too.

Next came a minor crisis. All the way through my Service career my dear Pat had been an exemplary Service wife, supportive, encouraging, putting up with bores, charming everybody she met, cleaning up quarters left not quite so clean by others, leaving quarters herself in a spick and span condition. She took one look inside this enormous house and broke down. She lay on the kitchen floor and wept. No, she was not going to clean this one up. It took a little while to calm her down. I felt so helpless. I did my best in the rest of that evening to make a few rooms look like a home. And when I went outside to empty the caravan, who should stroll out but the cat: she had been sleeping under a blanket all the time. That cheered us all up.

Within a few days I was lucky enough to meet the local British “Clerk of Works” who agreed that the house would warrant some redecoration at their expense. This, plus some work by our allotted Belgian batwoman – Mauricette – gradually cheered Pat to her normal resilient self and we were back on track domestically. Meanwhile, there was Jonathan’s education to arrange. He was now approaching four years old and had got to like being in the Brampton nursery school. He was too young for the British School of Brussels; but we soon fixed for him to attend a local Belgian (French-speaking) nursery school; he went there for a year and seemed to like it – there were quite a few American youngsters there. When the teacher discovered he could already read, she delegated to him the task of reading to the Americans; she was delighted for it kept them all quiet. After a year, he would upgrade to the British School.

Once the house had been cleaned and some essential decoration had been completed, the whole place took on our idea of a home – our 23rd. It had a basement for storage of this and that plus wine; it had three floors; on the ground floor was the living room, very large with panelled walls, and a kitchen; above there was a family room where I used to work, lots of bedrooms, and a couple of bathrooms; above the three floors there was an attic with a skylight; outside, a double garage with a self-contained flat above, presumably designed for servants, containing a large room which we set out as a playroom with a train layout for Jonathan. The house was built in 1913, and this was proudly indicated on the front elevation. The surrounding gardens covered about half an acre and there was adequate hard standing for the caravan. The early dismay was soon forgotten. One morning an untethered goat from next door wandered in: Mauricette shooed it out with a broom and, once outside, directed a hose up its derriere. It never returned.

The NATO environment was not new to me of course. I’m sure the personnel people back at the MOD took into account my experience in Paris when they selected me for the post in Brussels. You will recall that the French decided in 1966 to leave the integrated military structure of NATO, staying in only on the political side. This had meant that all the NATO units in France had been moved. SHAPE was now (late 1970) at Mons in southern Belgium and NATO Headquarters had shifted to Brussels. A brand new building had been constructed in the Evere district of northeast Brussels, on the way to the Airport. It was a short journey from Avenue Colonel Daumerie.

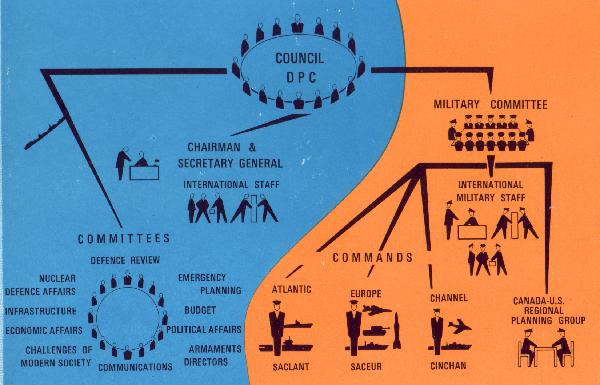

So what was I supposed to be doing in this place? Let’s start with the civilian side – the Council. The 15 member Governments (as it was in 1970) of the Alliance consulted and co-ordinated their policies through the medium of the North Atlantic Council (NAC), the highest authority in NATO. It normally met twice a year at Ministerial level, in one capital or another, with the 15 Foreign Ministers present. In permanent session the Council met at least once a week, often more frequently, at the level of Ambassadors (Permanent Representatives). Since France’s departure from the integrated military structure, the other 14 Permanent Representatives met to discuss purely defence matters as the Defence Planning Committee (DPC), usually at the same sessions. Similarly twice a year the DPC met at the level of Defence Ministers. All meetings were chaired by the Secretary General, who also directed an International Secretariat (IS) forming a number of Committees involved in such matters as Planning, Budget, Political Affairs, Communications, Economic Affairs, Infrastructure as well as Defence and Nuclear Affairs. Members of the IS were drawn from all 15 countries and were expected to work in the international interest.

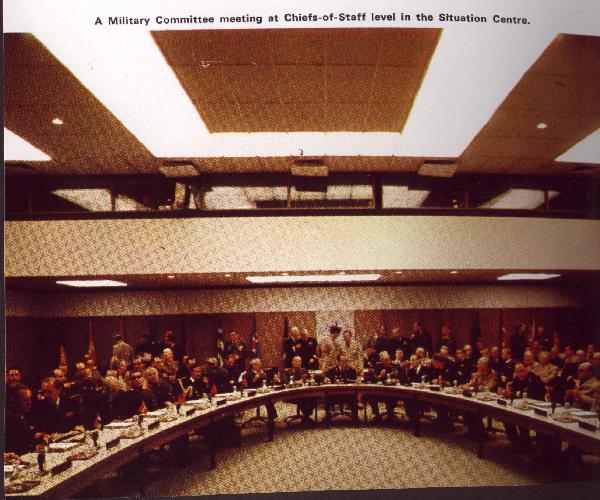

Now I turn to the military side: the senior military authority in NATO was the Military Committee (MC) which provided military advice to the Council and the DPC. It met twice a year or more at the level of the Chiefs-of-Staff of the thirteen member countries participating in NATO’s integrated military structure: thirteen, that is, resulting from France’s withdrawal and the fact that Iceland had no armed forces. At least once a week, it met in permanent session at the level of Permanent Military Representatives. These latter meetings were normally held in the Situation Centre which provided up-to-date facilities for NATO-wide communications and the display and processing of military data. The International Military Staff (IMS) was the executive agency of the Military Committee and was composed of staff officers of the three services drawn from the thirteen Allied nations contributing forces for the defence of the NATO area.

The IMS was headed by a Director of 3-star rank who was nominated by the member nations and selected by the Military Committee. He could be any nationality out of the 13, but not the same as the then Chairman of the MC. The Director was assisted by 6 officers, normally of 2-star rank, and a 1-star Secretary; the 6 ran operational planning divisions as follows – Intelligence; Plans and Policy; Organization, Exercises and Operations; Logistics; Communications; and Command, Control and Information Systems. As the executive agent of the MC, the IMS was tasked with ensuring that the policies and decisions of the MC were implemented. In addition the IMS prepared plans, initiated studies and recommended policy on matters of a military nature referred to NATO or the MC by various national or NATO authorities, commanders or agencies. Outside Brussels, in the field, the two main Allied Commanders were Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) and Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT). Agencies in various capitals encompassed work on Standardization, Aerospace Research & Development, Undersea Research Centre and others.

My job was that of the 1-star (Air Commodore) Secretary whose task was two-fold: as Secretary to the MC, to progress its work, and as Secretary of the IMS, to control its work programme resulting from MC decisions. It was no sinecure. It was not the relaxed atmosphere of my SHAPE days. There was never a dull moment. The interesting point about the Secretary’s post was its Britishness. The posts of the Director and his 6 Divisional heads were rotated through the 13 countries. For the Secretary’s post, however, it seemed to be tacitly agreed that a Brit should fill it more times than any other. Between 1968 and 1994, there were 10 Secretaries: one was from the Netherlands, one was Belgian, two were Canadian and six were British. I had taken over from a British Army Brigadier; I was to hand over in two and a half years time to a Royal Navy Commodore.

When I took office, the Chairman of the MC was a British Admiral Sir Nigel Henderson and his Deputy was an American, Lt Gen Ross Milton; the Director of the IMS was Greek – Lt Gen Palaiologopoulos. (We knew him as “Pally”.) The following year (1971) all three had changed, respectively, to Gen Johannes Steinhoff (GE), Lt Gen Ed Rowny (US) and Lt Gen Sir John Read (UK). It seemed that the US liked to retain the Deputy post – just to keep an eye on things in Brussels. Out in the field, of course, both Major Commanders were always American: SACEUR at this time was Gen Goodpaster, with whom I came to work closely at meetings; and Deputy SACEUR was always a Brit. (This was the sort of thing that got up the French noses.) I had two other Brits on my own staff – an RAF Gp Capt and a Naval Capt – together with a very efficient PA, Miss Beryl Furse.

Now – an important feature: all the people I’ve mentioned by name so far filled international posts. By contrast the British Permanent Representative on the MC, who was Gen Sir Victor FitzGeorge Balfour, was a national appointment. It was his job to put the UK point of view and fight for UK’s corner. I took the international feature of the Secretary’s job very seriously. I was a NATO officer, not a British officer. National views had to be submerged in the wider interest of achieving agreement among all the nations of NATO. There were times, indeed, when I had to be (politely) beastly to the Brits for what I considered to be unnecessary bloody-mindedness in holding up certain work. In these days of my retirement I’m sometimes irritated by the deliberate misreading of a situation by the media in respect of the work done by, say, an EU Commissioner such as Leon Brittain or Neil Kinnock. They have been holding international posts and they should think internationally; yet the mere fact that they conscientiously do so has drawn criticism that they were “going native”. Inaccurate and unjust.

Anyway, at a Special Meeting of the MC on Thursday, 29th October 1970, my staff had written Gen Milton’s opening remarks as follows: (the Admiral was away) – “It is suggested that you may wish to welcome Air Commodore D J Furner, Royal Air Force, the new Secretary. Furner is an air navigation specialist. He has had both command and staff experience, including over two years on staff duties in the Nuclear Operations Section at SHAPE. He joins the IMS after having commanded a station in Bomber Command and the Central Reconnaissance Establishment in Strike Command of the Royal Air Force.” There was a murmur of ‘hear hear’. I was in post. Note that it was Thursday: that was the regular day of the week for the MC meetings and, because of that, we all turned up at the office in uniform on Thursdays. All other days, it was mufti.

I suppose all Secretaries of any vintage would recall from their days in Brussels that the pressure was always the same: keep the nations going in the right direction, improving force levels assigned to the Alliance, maintaining effective training schedules, paying their fair share of infrastructure costs and doing their utmost to achieve annual NATO targets. In the early 1970s it was certainly like that, even to the extent of “naming and shaming” the backsliders in the common effort. The buzzword was “AD70”. It referred to a major study “Alliance Defence in the 1970s” which was adopted by the DPC in December 1970. The study set out goals in every sphere of NATO co-operation, including force level targets for each of the 13 nations. During my time in Brussels, AD 70 demanded continual prodding of all the nations. It was often a slow and painstaking process, because, you see, everything had to be decided on a consensus basis – no majority votes. Equally well-used buzzwords were “A Balance of Deterrence and Détente” (on the part of NATO); “Flexible Response” (also NATO, an upgrade from “trip-wire”); and “Peaceful Co-existence” (on the part of the Warsaw Pact).

Another well-known mnemonic in 1971 was MBFR. In its initial concept it stood for Mutual and Balanced Force Reductions. The aim was to steady the arms race between the West and the East but it proved to be a somewhat farcical argument between one type of arithmetic and another. NATO’s idea was for proportional cuts: eg “a quarter off ours, and a quarter off yours”. The Warsaw Pact saw things differently: eg “x off ours, and x off yours”. Well, the point was that the USSR’s front line forces had always been bigger than was perceived necessary for her own defence; indeed, they were designed (at that time) for an aggressive approach to NATO. It is obvious that their arithmetic would gradually whittle NATO down to a smaller and smaller proportion of Warsaw Pact levels. Hence MBFR was the sort of project which would run and run, for years if necessary. Not only were negotiations conducted between the two Alliances, but it also spread into the ill-defined gathering of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE).

There was an amusing side to MBFR. Manlio Brosio, who had been Secretary General of NATO until October 1971, was tasked with the initial discussions with the USSR and the other members of the Warsaw Pact; accordingly, he was given carte blanche to travel around Eastern capitals as he wished. MBFR soon became “Manlio Brosio’s Free Ride”, which was perhaps a trifle cynical. To us in the military, bearing in mind the different calculations that I’ve mentioned, MBFR became “Much Better For the Russians” which, you must agree, was quite neat.

One of the military staff whom I haven’t yet mentioned was the Personal Assistant who arrived to coincide with General Steinhoff. He was Gp Capt Michael Knight: he was ten years younger than I and I could soon tell that we had a very sharp character here indeed. I confidently forecast on his appraisal report that he would reach very high rank. (He did – he got to Air Chief Marshal and a member of the Air Force Board.) Anyway, between Knight, holding the Chairman’s hand, and myself, running the business of the Committee and the IMS – just two RAF types – we figured we had the place organised; particularly when Sir John Read took over from “Pally” as the Director of the IMS. Indeed, just to rub it in, at one point in my term of office, I worked on a reorganisation of the IMS, presented it to the MC, and had it all agreed.

Not everything happened in Brussels. I’ve mentioned that the Committee would meet occasionally at Ministerial level in one capital or another. To that end I flew to Montreal, Ottawa, Rome and Oslo at different times in order to prepare and record meetings. But this was all commercial flying. It came to be that my last military flight had been in September 1970 from Wyton to Norway and back in connection with the Norwegian survey.

I’ve not counted the meetings for which my staff and I were responsible for recording. If I chose to make a guess, it would be nearing 200. From such activity, at such distance in time, and without detailed diaries, it’s only odd little quirky things that are still in the memory box. Joseph Luns, who took over as Secretary General from Manlio Brosio, always wore red socks and always took his shoes off whilst chairing a meeting of the Council…….. Gen Steinhoff, although usually perfect in English, had trouble when a word like “albeit” was written for him – it came out as allbite……… there was a time when the Danes were in some disgrace because their Prime Minister had said the only defence policy he foresaw for his country was a taped message – “We surrender” – which brought forth from Helmut Schmidt, the German Defence Minister, an ostentatious flapping of his newspaper in the DPC whilst his Danish opposite number was speaking…….. you never placed Greeks and Turks together – either in meetings or at the dinner table……… I recall specifically racing up and down the corridors between the Greek and Turkish offices in order to achieve a consensus on a sticky point; (as I’ve said, everything had to be unanimous in NATO – and this particular point might well have been about naval boundaries – have a look at a map of the Aegean Sea and you’ll see what I mean!)…….. and, of course, there were the national Brits being cavalier about holding up important infrastructure implementation until they could get their way on something else they’d been bargaining for.

What I do remember was that the task kept me very busy indeed. It was a regular occurrence for me to set out papers in the family room on the first floor and work for many hours on a Sunday morning in order to catch up on the week. Jonathan got the point of that. He set out papers too, and said he had “wark” to do.

There was also a (considerable) social side to life in Brussels. Apart from our own Nationals, in NATO, in the EU and in the Embassy, we accepted invitations from pretty well every other NATO nation except Iceland. Pat was a tower of strength in all of this. I remember so well that the Reads (Director) had invited a large international party to dinner, with many different nationalities placed around a very long table in their quarter. Monica and John Read were a delightful couple. Pat and I were scattered around the table to add a bit of Brit support. At one stage during the dinner, there was one of those awful, longlasting silences when nobody was saying a single word; it seemed to go on for painful minutes (giving rise in my mind to that strange old adage – it must be twenty past or twenty to (?)); Pat spoke up loudly, something like – “Have any of you done any caravanning?” – and away we went. Monica Read looked very relieved. She came round to our house the next morning with some flowers for Pat – “These come to you with love”, she said.

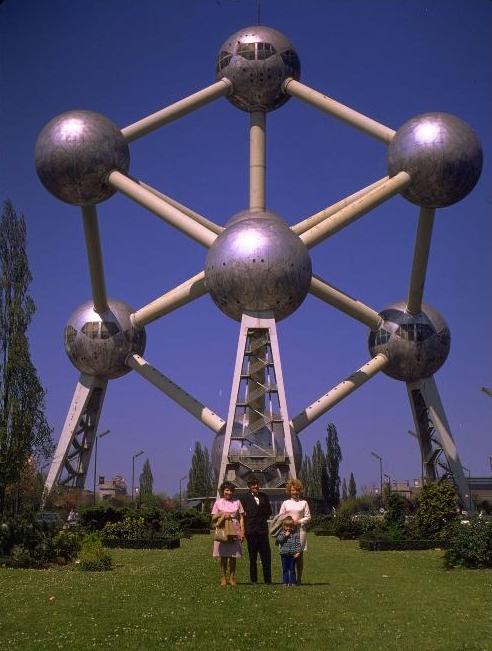

We had many visitors to Brussels – family mostly, from both Southend and Norwich. As with Paris, we drew up a fairly standard tour for everybody. It encompassed the Grande Place, the Atomium, Waterloo (where you would assume Napoleon won), Bruges, Namur and the impressive “sloping lock” at Ronquieres. We took holidays with all the family to Brittany once more, with Jonathan to Switzerland once more, and with a large party of all four of us plus Ray, Jane and David to Camp Capalonga in northern Italy near Venice; both of us pulled caravans on that one and I carried the boat, but – stupidly – forgot the sail! I remember that whenever we had to cross the border into Germany Peter would have some idea of a piece of electronic equipment that he needed and there would be an inordinate delay at the border (presumably very different today).

Mention of the family brings me to a number of highlights during the period 1971-72. Peter obtained his degree at the age of 22 and started off with full employment in IBM Croydon; and he was married to the lovely Patricia (now shortened to Tricia) in February 1972. Pat and I travelled across the Channel for that occasion at Hailsham, and Richard came down from Stamford. Richard was now in the VIth Form and was taking ‘A’ Levels; and was selected to play the first movement of the Schumann Piano Concerto on Speech Day. (We still have a recording of the performance.) Jonathan switched to the British School of Brussels in early 1972 at 5 years old. We – Pat and I – celebrated our 25th (Silver) Wedding Anniversary shortly before we left Brussels.

Yes, we had to leave Brussels in February 1973. I had been told by the MOD at the end of 1972 that I was to take up a newly created post in London with the acting rank of Air Vice-Marshal, which was a most exciting surprise. The build up to the departure was hectic. The last couple of months concentrated the mind wonderfully, as they say: tidying up the work for my successor, responding to many kind social invitations, and organising an enormous farewell party of our own, for which we had to hire a hall somewhere.

As a departing gift to all the Permanent Representatives of the MC and as a bit of a joke, I organised the production of a cartoon with head photographs of them all superimposed, together with speech balloons for each of them containing some appropriate comment. The cartoon was entitled the MCPS – the Military Committee in (not Permanent) Philharmonic Session. Gen Steinhoff held the baton – “I know the score – by God!” Gen Milton (now the US Rep) was on the drums – “You guys have got to keep up with the tempo. Less of the adagios and a touch more of the allegros.” Gen Rowny (Deputy Chairman) played a mouth organ – “I play it by ear.” Gen Balfour (UK) was one of the first violins – “Don’t you think that semiquaver should have been a quaver? Perhaps we should go back to Bar 22.” (A mischievous reference to the UK holding up the 22nd “slice” of infrastructure costs.) And so on………watched from the sidelines by the presenter (Director – Sir John Read), picking up his manner of speech – “ This is indeed the Military Committee in Philharmonic Session, and they are making – what you might call – a concerted effort.”

The nicest compliment paid to me – and forgive me my immodesty, but this was fun and at the same time sort of summed up the job – was by US General Ed Rowny, Steinhoff’s Deputy who, at a farewell dinner, read out the following:

Our purpose tonight: to honor Jack Furner,

As task-master, we’ve had no sterner.

A real after-burner –

Farewell to the keeper of schedules and agenda,

Of whites, pinks, revisions and addenda.

All knew he’d arrived at work each day,

His footsteps reverberating – the long hallway.

Jack was nimble, Jack was quick

With many a bon mot and often knit-pick

Who did- Lord Knows what? (or whom?) during lunch hours,

Exercizing skillfully stealthful editing powers.

Our impressario with jokes, charts and animation

Witty and sly and ingenious at mensuration

Patient and long suffering with reorganization

Ever perspicacious at rare improvisation.

A smile per second, a bawdy story each minute,

With Thursday morning changes – how did he do it?

He returns to the UK, inflation and new house

The latter – one assumes – agreeable to spouse.

Goodbye luncheons and libations to test one’s strength

Small wonder he reached new heights, holding forth at great length.

Jack’s finest hour comes now as we say goodbye,

And he reminisces: What a Secretary was I?

What a Secretary he? A question quite silly.

Erste klasse, primus inter pares

In English-English: a dilly.

General Rowny went back to Washington soon after I had left and became an important figure within the Federal Government on the subject of the SALT talks – another one of those acronyms, Strategic Arms Limitation Talks.

He had described me in a letter in 1971 as “the key cog in this machinery”. I don’t know about that: a small cog, yes, fulfilling a challenging and fascinating task. Indeed, the 1970s were challenging times for NATO, but the Alliance continued to hold firm all the way to the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the subsequent breaking up of what we had called for 70 years the USSR. NATO eschewed boastful words but the Cold War had been won.

As I look back at the turn of the Century, let us hope that the French have not fouled up the whole idea of NATO and US participation by their cavalier approach to a separate “European Army”.