I was now approaching 70 – and, although I didn’t realise it at the time, a lot of voluntary work. Soon after Pat and I had returned from the memorable trip around the world, a friend of Alan Clark asked me if I would take on a task for a Charity. He was Kurt Lewenhak, a Hungarian Jew (not devout) who had been in the same outfit as Alan during the war and had subsequently made a career in television directing documentaries. His wife was Sheila, a PhD and a somewhat forbidding environmentalist – more on her later. Kurt was working on a Committee which had just been set up to run the affairs of what they called the Eastbourne Arts Centre: they had taken over the basement floor of the main Eastbourne Library, which was equipped with a stage, auditorium, foyer and refreshment room, in order to welcome travelling professional players and musical performers. The Arts Centre was looking for a Treasurer. It sounded right up my street. I said yes.

The Chairman was Ernest Wiegand, same age as myself, who had flown Mosquitos as a navigator during WWII: we clicked with each other immediately. All the others – Secretary, Events, advertising, refreshments and so on – were eager volunteers and they were all a very happy and altruistic band of people. It soon became clear that the Treasurer should ideally take over the membership database since there were annual subscriptions to collect and it made sense to combine the tasks. By this time I had graduated through various upgrades of computer and it was a simple matter to automate the whole thing, including labels for any mail-out. We met as a Committee once a month; Pat and I usually attended most of the events; and keeping the accounts straight was almost a daily task.

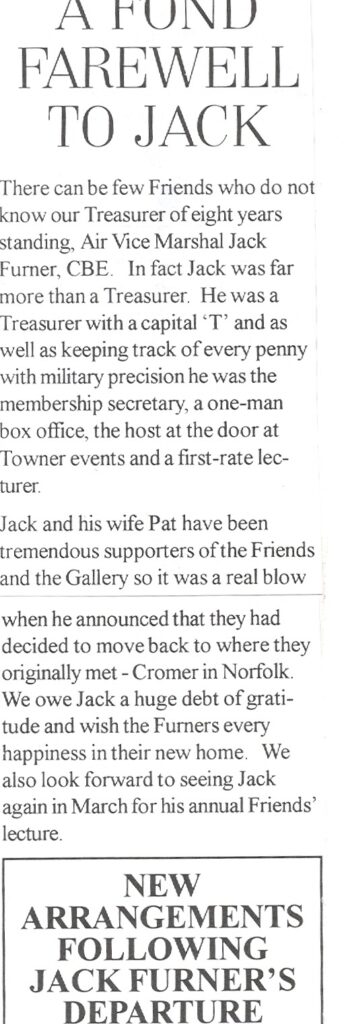

Next I came to the notice of an organisation – another Charity – known as The Friends of the Towner. The Towner Art Gallery and Museum was housed in an elegant building in the old part of Eastbourne. The Friends had been set up many years before to arrange cultural events from time to time in the long room of the Gallery, with the aim of making money to be donated to the Gallery for additional acquisitions. The Friends’ Committee was looking for a Treasurer. I said yes. The Chairman had just changed: the new man was ex-BBC “Folk on Two” Jim Lloyd. He and I talked at length about the aims of the Friends. I had gone back into the books of the previous 10 years or so, and it seemed to me that a lot of effort had produced comparatively little help to the Gallery. Indeed, I understand that the view in the local Borough Council was that the Friends were little more than a social club. Jim Lloyd and I started to set in place an organisation and procedures which were designed to provide optimum aid to the Gallery. Within the seven years that we worked together, I was able fairly quickly to raise net profit from very little to £9,000 or so per annum. In order to control all features affecting finance, I gradually took on the membership database, the printing of membership cards, the printing and sale of tickets for all events, the printing of posters and the organising of mail-outs. It was a most enjoyable task. When I finally had to hand it all over in 1997, they distributed what I had been doing to five other people: I trust they find it easy to co-ordinate. Needless to say, there were regular Committee meetings; and Pat and I again attended most of the events.

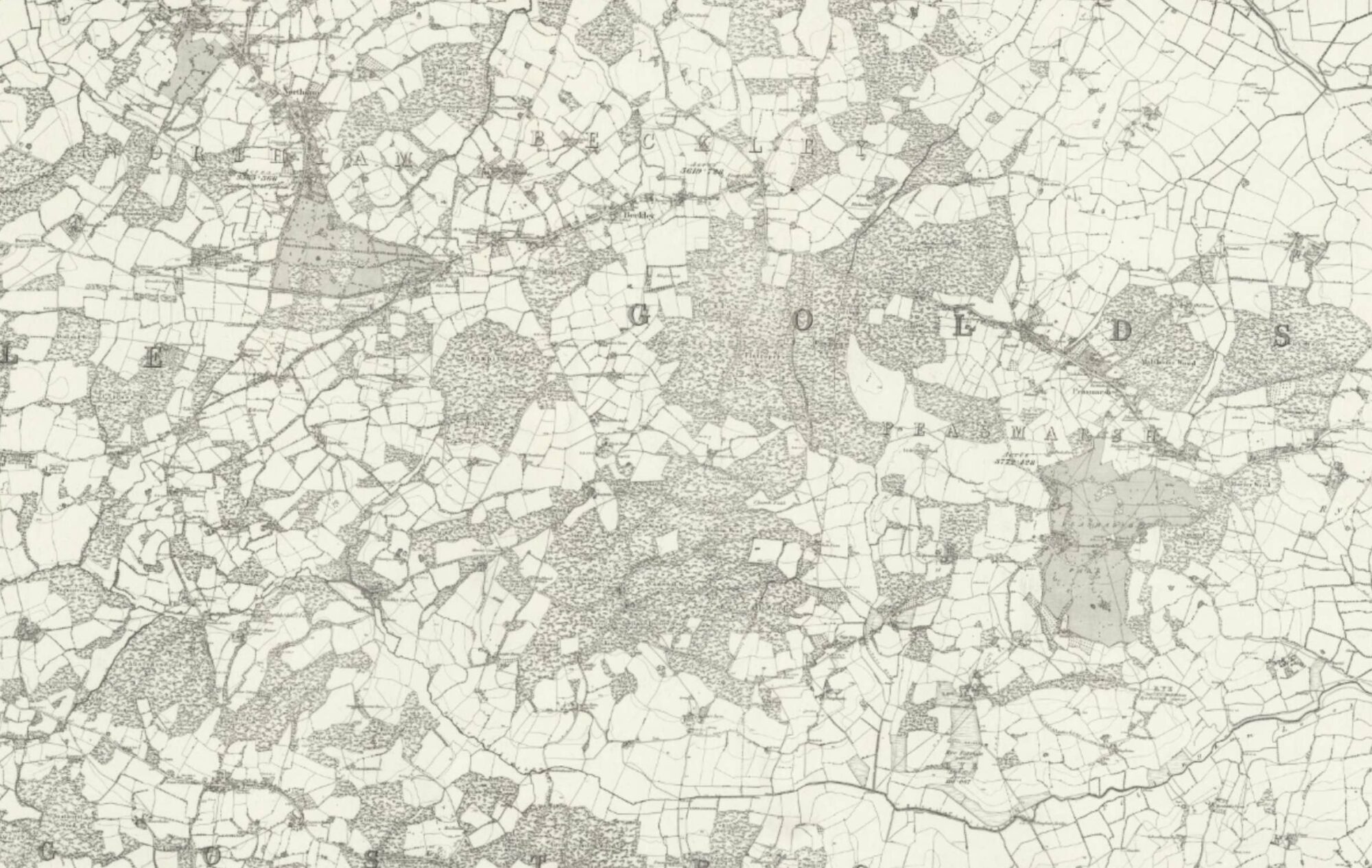

Now some of the events at the Towner were musical presentations, for instance, by Robin Gregory, also of Radio 2 fame, who would put together a series of comments and pieces of recorded music to illustrate a particular theme. I thought to myself, I used to do that a long time ago – during the war at Blickling Hall and out in Burma just after the war. Why not here and now? I set myself a three-fold task having selected the first such effort – it was Prokofiev’s centenary in 1993. First, develop a script on the The Life and Works of Prokofiev: start from Grove, consult quotation books, biographies, musical anecdotes, critics’ views, add up to about 4000 words for half an hour’s speaking; second, select a representative group of pieces of music to fit the script, totalling about an hour; third, prepare slides of relevant photographs to provide visual aids; divide the whole into two halves of 45 minutes each to provide an interval for the bar. In the interests of ease of flow, I taped all the music from CDs – in this first case, on metal audio tape, but subsequently on advice from eldest son Peter, on video tape which was a great improvement. [In 2001, the CD Recorder comes into play.] Anyway, Prokofiev seemed to go off well – I put it on first at the Towner and was later asked to repeat it at the Arts Centre and various other groups such as U3A, and this became the usual pattern. Year by year after Prokofiev, I did the same for Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, then the Mighty Handful, and finally (for Eastbourne) The Tingle Factor, a personal backs-of-hair selection. Somewhere in between the purely musical efforts, I inserted, just for fun, Weather of the World…and Eastbourne, with music. All were performed first at the Towner, later to other groups – the Arts Centre, U3A and the Recorded Music Society. I’m glad to say that they were all well received.

Then there was the Eastbourne Branch of the European Movement. Pat and I had been attending some of their dinners because they invited interesting speakers. I was invited on to their Committee of Management. The Chairman was getting a little frail and he asked if I would take over. I said yes. More meetings every month and organisation and preparing introductory speaking at dinners. They were fun.

My musical efforts were noticed in another quarter. Round about 1995 I was approached to see whether I could take over the Presidency of the Eastbourne Sinfonia, now to be renamed the Eastbourne Symphony Orchestra. Of course I said yes. More meetings and organising.

You remember I mentioned Kurt Lewenhak’s wife Sheila. She was running a Charity all on her own called “Save our Seabirds” and she wanted a Treasurer. I said yes. Sheila was very concerned about oil spillages, rubbish on our beaches, the disposal of sewage into the English Channel, and that sort of thing. It turned out that the job involved a bit more than the finances. Because I had a camcorder, Kurt took me out on a rickety old boat one blustery day with my video camera to investigate and film the out-turn of sewage off Pevensey Bay. It was fairly easy to find it – follow the seagulls and the smell. That was one of the more unpleasant voluntary jobs, but old Kurt made a decently edited film of it which got shown in the local cinema!

All of the foregoing was most rewarding. It was all unpaid, of course, but it contributed to keeping my mind alert and in tune with everything going on around us. As if this little list wasn’t enough, there was another post to which I was invited which demanded almost as much work as all the rest put together.

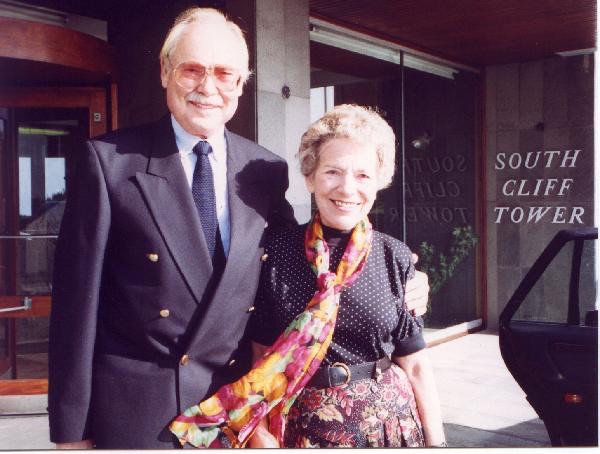

At this point I should explain that, of the 72 residents in South Cliff Tower, only about half had shares in the Collective Freehold. The other half paid ground rent to the Freehold Company, and the latter paid out dividends from time to time to the shareholders (a bad practice, I thought, but still). Because only half of the residents thus attended the AGM of the Freehold Company, there had to a Residents’ Association to which all residents belonged. Soon after Pat and I returned from our round-the-world trip, I was asked to consider taking over the Chair of the Association from an elderly man who was ailing. The responsibilities did not appear too onerous, running an annual meeting and keeping the Freehold Company on its toes, so I accepted the job. Well – and here’s the main point – a year or so after that, the Chairman of the Company asked to see me: I presumed he was going to ask me to join the Board as another Director. No, he wanted me to take over from him as the Chairman of the Freehold Company – South Cliff Tower (Eastbourne) Ltd. That was a fast one, and one I hadn’t expected. I asked for 24 hours. I discussed it with Pat. I discussed it with the Company’s Secretary – a most dedicated and experienced man named Clifford Grinsted. Indeed, he was for a year the Master of the Livery of Company Secretaries: they don’t come more experienced than that. Knowing he was there to back me up, I agreed.

That decision involved me in a mass of work, some rewarding, some highly unpleasant. The old adage that you cannot satisfy all of the people all of the time could not have been truer in these circumstances. Out of the 72, most were understanding, sympathetic and helpful; but there were a few who were downright inimical and preferred to hinder rather than help.

Of all the business that came up during my Chairmanship were the following:

Clearing up an asbestos mess in the loft of the building and persuading the BBC to cough up a disproportionate part of the £40,000 cost; the BBC had an installation in the loft.

Squeezing out of a well-known mobile phone company (Mercury) a handsome annual rent for sticking their gadget on the top of the building.

Protecting garage roofs positioned under the gardens from dripping ooze on cars.

Attempting to put right some shoddy workmanship thirty years before which allowed leaking of storm rains through the west wall at all levels; going up and down the wall on cradles looking for cracks.

Overseeing a £150,000 per annum budget spent on three porters, four lifts, maintenance, gardening, insurance, professional fees; and funded by up to £2,000 per annum Service Charges.

Gradually recruiting more to be shareholders of the Collective Freehold Company, from about half to two-thirds; the Company had preceded the drafting of a Bill by Parliament to enforce the option of collective freehold.

Walking on the domed roof of the building, 21 floors up, to inspect the covering (in calm conditions!

With 72 apartments, you’re bound to collect a few memories of strange happenings: for instance the resident who:

Requested from the Company the sum of £500 being recompense for carpets left behind in the loft after de-asbetosing, said carpets having been condemned by the asbestos removal experts and buried somewhere in Kent; fortunately not realising (to this day) that her spouse surreptitiously made recompense to the Company in cash.

Was a millionaire with two Rolls-Royces and who insisted that a check be made on the use of the Hoover on his outside landing, to ensure that no electricity units were being fed into his meter.

Complained to the Senior Postmaster because in-house mail had been removed from the post-box in the foyer three minutes early.

Suggested the idea of transferring proceeds from a leasehold extension sale to the Reserve Account; subsequently chose not to purchase the extension; received significant dividends stemming from the sale; and contributed nothing to the Reserve Account.

Authorised the sending of a disgracefully threatening solicitor’s letter to a close neighbour, an elderly widow whom I as Chairman found myself consoling in her distress.

Was 90 years old and lambasted the Chairman for informing his daughter after he had placed his life – and that of others – in jeopardy with an unlit gas ring.

Accused the Chairman of being a little Hitler because he had authorised an experiment to see whether electricity units could be saved in the garages – say, after 2 am.

Commented “over my dead body” when it was first suggested that it would be a good idea to keep the garage doors locked at all times, allowing (electronic) opening only for entry and exit; said resident subsequently giving up driving altogether.

After being informed of the Mercury arrangement (phone installation and rental), requested confirmation that “the directors of SCT have no vested interest in Mercury, the whole matter having a strong flavour of a ‘kickback’ arrangement”.

And finally (just for fun) the Resident who was a senior and very well-known weather forecaster in the BBC and on the day when the Red Arrows were due for a display, and after I had said to the Head Porter – there will be no display today, only a single flypast, very poor visibility – assembled a dozen or so guests on his 14th floor balcony to watch them do a single flypast.

Looking back on it all, I think the “kickback” insult was the final straw: what was I doing, working for these people? I know they were only a minority. But in a way, it was the straw that triggered a chain of events which culminated in our 28th move in 1997.

So now I’ve dealt with all the things I was doing in Eastbourne: there was a time when all of these were running concurrently:

Treasurer and Membership Secretary of the Arts Centre; Treasurer and Membership Secretary of the Friends of the Towner Art Gallery; Treasurer and camera man of Save our Seabirds; President of the Eastbourne Symphony Orchestra; Chairman of the Eastbourne Branch of the European Movement; Presenter of musical programmes to various organisations; Chairman of South Cliff Tower (Eastbourne) Ltd.

Much of the work was rewarding in that you felt a sense of achievement. The trouble was that our diary became so full that we could hardly get away for a holiday. We managed it from time to time by sensible delegation.

The Netherlands was a must each year to keep up-to-date with Richard and Sue and their growing family: Simon in 1991, Colin in 1993, brought the total of our grandchildren to 7; and each time we visited them, they had chosen new sights for us to see. I flew to Canada to link up with the Buchanans and attend the very last of reunions arranged by the Wartime Pilots’ and Observers’ Association based in Winnipeg. During the Tennis Week in Eastbourne in 1991, which Pat attended with two of her school friends, I took off to San Pedro where my brother Ken was now on his own again, his second marriage having failed. He had a large and beautiful apartment which was his to sell, so I helped out by putting together a video to Ken’s commentary. Pat and I managed to do a lot of driving around the UK – on separate occasions the Southwest, Malvern (Elgar’s home with the sign “Please Boult the Gate”), Sidmouth, Bournemouth, Torquay, Aberdeen, Lake District, Jersey ….

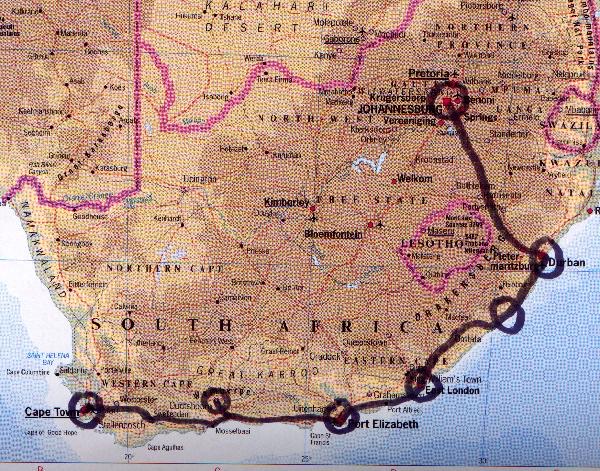

And in 1995, we went to South Africa to see Pat’s sister Betty. She was living with Simo in Margate on the east Natal coast south of Durban. We flew to Johannesburg, hired a car, drove to Betty’s, stayed with them a few days, then set off through the Transkei and the Ciskei to Port Elizabeth and through Knysna and George to the Cape, staying at Gordon’s Bay. After seeing the sights, we retraced our steps, staying a further period with Betty before saying farewell – until…?

We left South Africa with many wonderful sights and happenings in our mind, in particular the magic of standing at the Cape of Good Hope with nothing between us and the Antarctic. The name of that Cape sums up the future for the country. Good Hope. If they can get their act together – Blacks and Blacks, Whites and Whites, Blacks and Whites and Coloureds – they could together create a wealthy nation. Many are pessimistic: aspirations will not be met; there will be resentment. If there are more men like Mandela, men with integrity and statesmanlike qualities, to follow him, perhaps they can keep their people with them whilst their plans take so long to come to fruition. The international community must hope so.

In addition to the local attractions at the Eastbourne Arts Centre and the Towner Art Gallery, we continued to take an interest in the West End scene and particularly memorable were Sleuth, Miss Saigon, Sunset Boulevard, An Inspector Calls (brilliant staging), Chess, Amadeus (I used the dramatic cry of Salieri imagining the sound of Mass in C in my “Tingle Factor”).

Through the close friendship of Frances Line, almost about to retire as Controller Radio 2, we were able to be present at a 70th birthday concert for Malcolm Arnold: the joyful Piano Concerto for three Hands gave me another Tingle. She invited us also to a number of Friday Night is Music Night concerts, a 50th Anniversary Concert for the Battle of Britain and a Promenade Concert featuring the extraordinary opera by Prokofiev, The Fiery Angel. After retirement Frances took a very active role in the Friends of the Towner and, amongst other things, edited the four Newsletters a year produced by the Friends.

We continued also with as many of the Foyles Literary Luncheons as we could manage. During this period the Guests of Honour were Edward Heath, Yehudi Menuhin, Lord Zuckerman, Margaret Thatcher, Frederick Forsyth, General de la Billiere and Douglas Fairbanks. For the last three occasions Pat and I were invited as non-paying guests, which was a very pleasant and unexpected surprise.

It was obvious that the 1990s would feature a number of 50th Anniversaries. After the Battle of Britain came many more: I attended a memorial occasion at Chedburgh and wrote a preface to a book produced by people of the village; I spoke at a ceremony to dedicate a stone at Oulton; I was invited (and took Ken along with me) to the Heads of State Ceremony in Hyde Park for the 50th Anniversary of VE Day with its inspired moment of the Heads of State being led by the hands of young children from all countries; I spoke on 11th November of the same year to Clifford Grinsted’s Livery of Company Secretaries on “Looking Back 50 Years”; and I spoke to the European Movement on the history of NATO. Coincidentally, this period also included a somewhat subdued occasion of the closing of RAF Scampton. [It reopened later to accommodate the Red Arrows.]

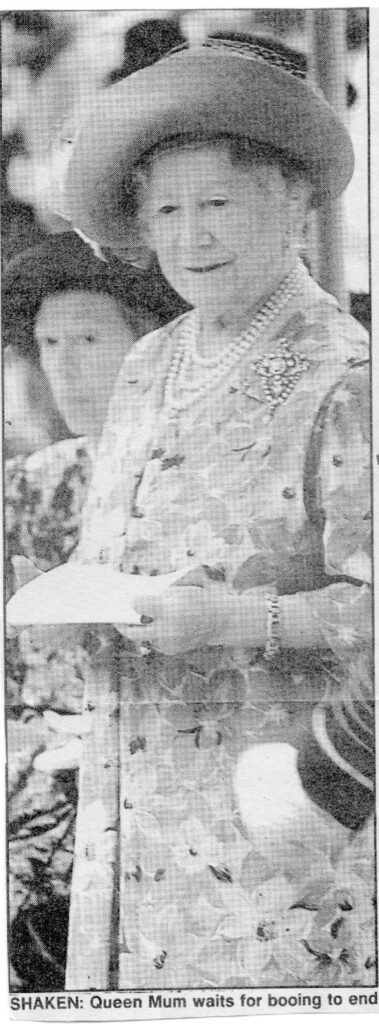

It seemed that the decade was noteworthy historically in that a number of additional books appeared on Bomber Command: I was asked to contribute in small ways, for instance, to The Hardest Vistory by Denis Richards, Courage and Air Warfare by Mark Wells and The Bomber War by Robin Neillands. And it was in 1993 that I saw the Queen Mother, as patron of the Bomber Command Association, quietly undeterred by paint-throwing yobs as she unveiled a new statue of Bomber Harris outside St Clement Danes and spoke of the 50 years of peace which our war efforts had engendered.

What of the family in the 1990s? The saddest event early on was the passing of Did, Pat’s mother. The poor lady had been eking out a minimal existence for four years since her stroke: her life came to an end in 1990. She had led a good and hard-working life.

My dear Pat gave me a nasty scare one day. We were due to meet somewhere in town after she had had a hair-do. She didn’t turn up on time; I waited – nothing; I went round to the hairdresser – they told me the police had been in to report that Pat had had an accident and had been taken to hospital. I sped over to the hospital: Pat was in a state of shock and dishevelled in A & E. She had had a fall on an uneven paving stone and went straight down on to her face, not daring to risk an arm in the fall. The police station was opposite: a policeman on duty had seen her fall and came over immediately to assist her. Her face was badly cut and bruised; her eyes were red with weeping; and her nose was badly damaged. I felt so sad for her. The A & E department of the hospital persuaded her that she should have a minor operation there and then on the nose in order to straighten it out. If she had left it, she would have joined a two-year queue to have anything done. I was so relieved that she was convinced: she went under an anaesthetic and they did a good job on the nose. She eventually looked as pretty as ever. For all the subsequent years since that incident, I have held on tight to her when we’ve been together: after all, there are uneven pavements all over the place.

Peter and Tricia were still living in their large Edwardian house in Purley, both children doing well at their schools. Peter moved from IBM to one of their customers, Commercial Union, and Tricia began working full-time as a microbiologist specialist in a local school. James was doing well at the local public school Whitgift, and had earned himself a whole table-ful of medals, crests and cups for his prowess at table tennis.

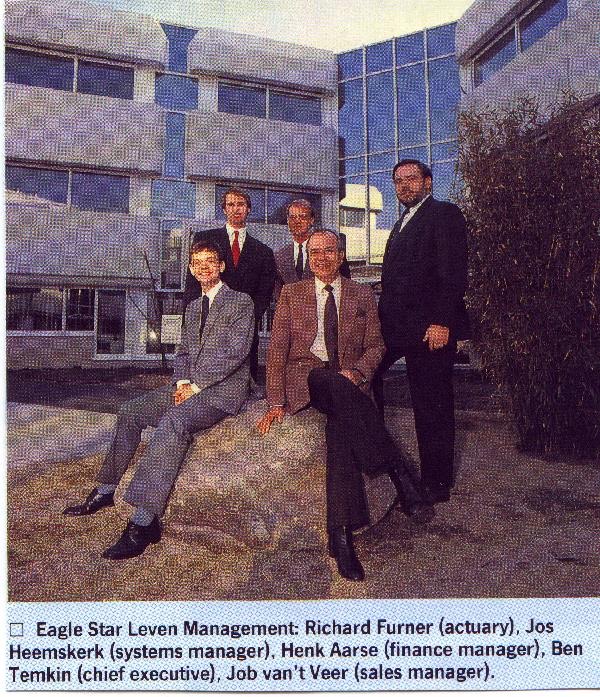

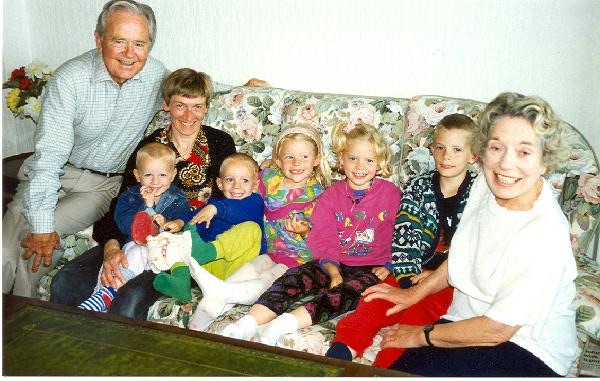

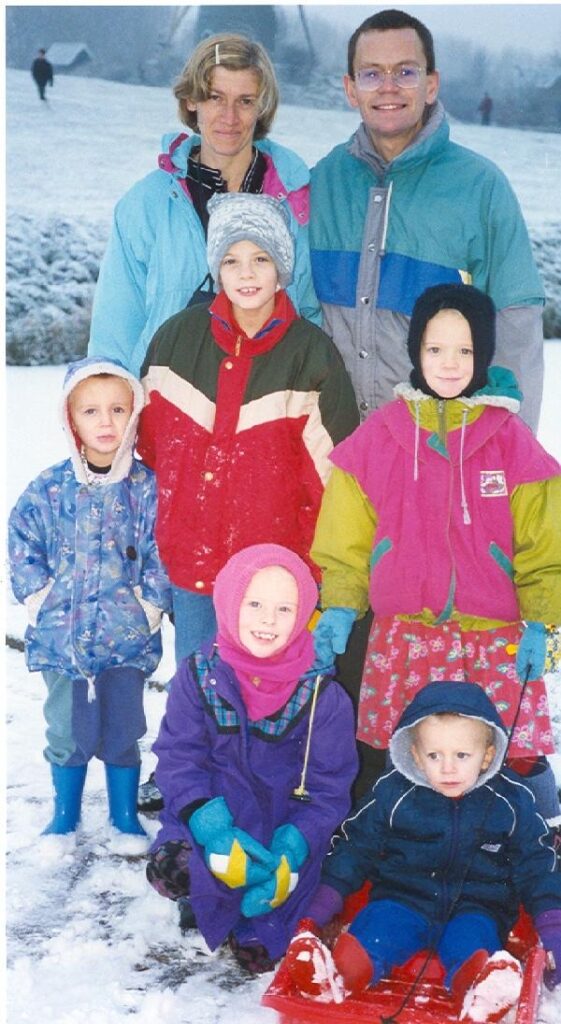

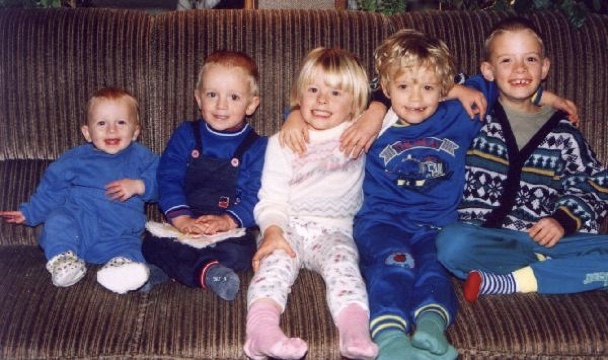

Richard and Sue remained in The Netherlands with their (now) five children. He was the Chief Actuary for Eagle Star Leven and of course it was entirely in character that the ages of the five (in the month of August) should present an arithmetic progression – in odd years, all even, and vice versa; for instance, by 1995, 10- 8- 6- 4- 2. Sue started doing dangerous things, like leaping out of aircraft with a parachute, learning to fly, and running and walking marathons. The eldest, Graham, came to Eastbourne one summer to stay with us for a week (lots of swimming) and the following summer the two girls, Julia and Claire, joined us for outings like Legoland, the Butterfly Centre – and more swimming.

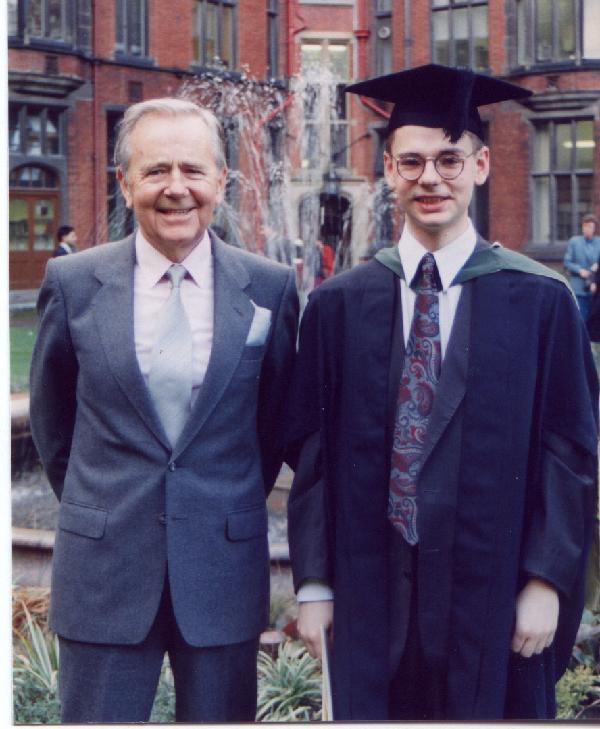

Jonathan enjoyed some very varied activities whilst Pat and I were living at Eastbourne. There was a short period at a couple of banks (one of them the State Bank of India, renamed from the Imperial for which I worked in 1939 – they very much wanted him to stay). He had a go as “Customer Services Executive” in ORBIT, one of Robert Maxwell’s Companies. But it wasn’t long before he decided to get back to academia: he hied off to the University of Sheffield and worked very hard for an MSc which he was awarded in 1992 in addition to a special Prize. After some research work and authoring of papers on Information Studies, he advanced, still at Sheffield, towards a PhD, awarded in 1995. Pat and I were able to be present at both conferments. Whilst at Sheffield he fell in love with a sweet young lady named Natalie Cole. They both moved to Aberdeen where he took a post as lecturer at the Robert Gordon University. They married in the Scottish countryside on 18th April 1997, Natalie’s birthday. Natalie later achieved her own PhD. Since it is common practice nowadays for the ladies to retain their own surnames, we address them on items of mail as Dr Jonathan and Dr Natalie.

My brother Ken also married again – for the third time – to Penny, in 1995, and they moved from Spain to South Africa. So it was that both our Best Man and our Chief Bridesmaid were now in South Africa: funny how it happens.

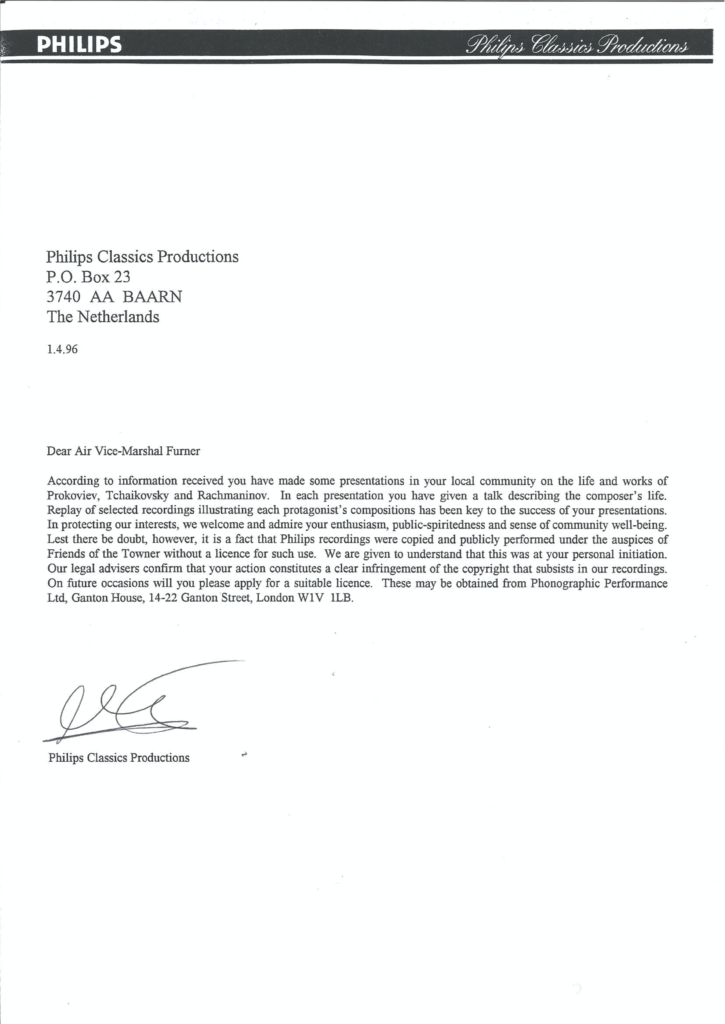

In early April 1996 I received the following letter from Philips Classics Productions, The Netherlands, dated 1.4.96:

On a quick first reading, I was muttering “Oh my Lord!”. Then I noticed the date and the typed word Leven at the top of the paper. Brilliant! It was of course from Richard on April Fools’ Day. [I didn’t notice at first, Pat did: look at the initial capital letters of each line!]

Another amusing episode was my involvement in the BBC radio programme Any Questions. The programme was scheduled to take place, or at least recorded, in the assembly hall of a local private school only a quarter of a mile from South Cliff Tower – on 6th October 1995. Questions were being asked for in advance. Around about that time I was having a chat with Peter, my eldest son, and he came up with a corker – at least, I thought it was. It was topical and clever. I typed it out and submitted it to the school office in good time. It read:

“Assuming that Professor Hawking is correct and that time travel will be possible, which event would members of the panel most wish to go back and change?”

On the day of the recording, I was told to be ready with my question, but only as a spare if there were time. All of us questioners were placed in the front row facing the panel consisting of the Chairman plus four, one of them being Dominic Lawson, then Editor of the Spectator. The programme got going with half a dozen questions formed from news items of the times, political, economic, TV, celebrities, etc; and it seemed they would not be able to reach me. However, to select something “rather different” at the end, the Chairman skipped the chap before me and asked me to put my question. There was a stir around the school hall, but the four panellists, I’m afraid, gave pretty banal answers – “I’d go back to such and such a year and change the result of such and such a football match….” On occasions there is time for the Chairman to ask the questionner to give his own answer, and I was ready with what I thought was thought-provoking. But the chance didn’t come and the programme was over. I reckoned that Lawson was the sort of chap who might be interested in my reply. I wrote to him at the Spectator: “I would go back to 1888 in the small town of Braunau am Inn, Austria-Hungary, and I would seek out one Alois Schicklgruber, and ensure that he was given a vasectomy.” Dominic Lawson’s reply was – “I think your own answer to your question was brilliant and I am only furious that you didn’t leak the answer to me in advance so I could have milked the resulting applause.”

Our time in Eastbourne was fruitful and full of interest. But the pressures of running South Cliff Tower, particularly bearing in mind some of the harsh brickbats that were coming my way, persuaded us to get ready to leave the Tower. We had spotted a very nice bungalow on the outskirts of the town and were keen on buying it. It had everything we needed and was exceedingly well-equipped. On the face of it, it also seemed to be in a good state of decoration. Nevertheless, a local surveyor friend strongly advised us to call for a survey and he offered to carry out a search. It took him only a day or two to discover that two years before the bungalow had been flooded (there was a tiny stream at the bottom of the garden) and that the whole place had been under a foot of water for several weeks. The owners had said nothing, of course, neither had the selling agents. This was bad news for us. We already had a buyer standing by for the apartment. Just at that very time, we had a ’phone call from Ray, Pat’s brother to tell us that there was a super apartment about to be completed in his complex in Cromer. On the spur of the moment, we sped up to Cromer and saw the builder at the apartment. It was a shell, but I could see it was going to be delightful – a huge living room of 450 square feet, a dining room, two bedrooms, two bathrooms, a study and fully-equipped kitchen, and a real 21st Century central heating installation: a total of 1700 square feet not counting two large balconies. The complex comprised 24 apartments, 12 on the ground floor, 12 on the first floor, all different in internal design. Rooms were spacious and quality was high. We agreed a date for moving in two months hence.

So – a completely different plan emerged. We were to leave the south coast and move to a north-facing coast. Instead of giving up simply the task of running South Cliff Tower, I had to start writing apologetic letters to all those other organisations who relied on my efforts, and to urge them to find replacements as soon as possible. It was a busy two months handing everything over: farewells all over the town – and the Mayor of Eastbourne was kind enough to mark my departure with a small reception and the gift of a plaque.

My story is now up to October 1997 and Pat and I made our 28th move a month or so before my 76th birthday. And there was a strange coincidence – as soon as we arrived in Eastbourne, we had celebrated our Ruby Wedding; now we were to prepare within a few months for our Golden.