Published in the Daily Telegraph, 24 January 2007

Air Vice-Marshal Jack Furner, who has died aged 85, flew wartime operations with Bomber Command and took part in secret electronic counter-measure sorties on D-Day; in peacetime he made a major contribution to the development of the RAF’s nuclear capability during the Cold War.

Furner was a specialist navigator when, in 1957, he was selected to command the operations wing at RAF Waddington, home of the first Vulcan V-bomber squadrons. With his expert knowledge of the aircraft’s navigation and bombing systems, he provided support for the training of new crews as well as the development of its operational capability; and in 1958 he was the navigator of the Vulcan that broke the Ottawa to London record (in 5 hours 45 minutes).

With the rapid expansion of the V-Force, Furner was appointed to HQ Bomber Command to head the operational plans division, where he had the task of planning the action to be taken by Britain’s 144 V-bombers and 60 Thor ballistic missiles in time of war. It was a job with “a strange air of unreality”, he recalled afterwards.

As the Cuban missile crisis developed, the atmosphere in the Bomber Command operational bunker became tense, and Furner’s immediate superior described him as “a tower of strength”.

Derek Jack Furner was born at Southend on November 14 1921, and was educated at Westcliff High School, where he excelled at mathematics. After a brief period working for the Imperial Bank of India he was called up, and volunteered for flying duties as a navigator. He was sent to Canada under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.

In March 1943 Furner joined No 214 Squadron, flying the Stirling four-engine bomber. He flew 25 operations, including the major “firestorm” raids against Hamburg. On the night of August 17 his squadron was briefed to attack the scientific establishment at Peenemünde on the Baltic coast. Reconnaissance photographs had identified the site as the development centre for Hitler’s terror weapons, the V-1 flying bomb and V-2 rocket. The raid successfully delayed their development, but 40 bombers failed to return.

When Furner and his crew completed their tour a few weeks later, they were one of only two crews to survive the six-month period. He was awarded the DFC.

After a brief rest Furner volunteered to return to operations as the navigation leader of his old squadron, which was re-equipping with the US B-17 Flying Fortress to operate in the secret world of electronic counter-measures. The squadron’s role was to fly in support of the main bomber force and jam enemy radar and radio communications. On the night of the D-Day landings, Furner was airborne, jamming the enemy’s early warning radar sites by dropping strips of tin foil. His aircraft was attacked and damaged by a German night fighter.

In early 1945 Furner transferred to Transport Command and was sent to India, where he flew Dakotas on re-supply operations in support of the advance in Burma. As the war ended he flew many sorties to Saigon and Bangkok to repatriate Allied PoWs, then remained in the Far East for a further two years flying VIPs and transport operations from Hong Kong and Singapore.

After a period as a navigation instructor he attended the RAF’s specialist navigation course in 1950 before moving to Boscombe Down, where he was involved in the development of bombing and navigation aids, including the first Doppler equipment.

These became the core of most of the RAF’s operational aircraft systems for the next three decades. He was awarded the AFC.

Furner spent two years on similar work with the USAF Weapons Guidance Laboratory, flying most of their strategic bombers before returning to complete the Flying College course and taking up his appointment at Waddington.

After three years in charge of the Nuclear Activities Branch at HQ Shape in Paris, Furner spent two years in the Ministry of Defence before taking command in 1968 of RAF Scampton, home of three Vulcan squadrons equipped with the Blue Steel stand-off weapon. He was the first navigator to command an operational flying station in peacetime.

In 1969 he took command of the Central Reconnaissance Establishment, then had two years as secretary to the Military Committee of Nato. At the end of this tour he was promoted to air vice-marshal, one of the first two navigators to reach the rank. He spent the last two years of his service as the Assistant Air Secretary with responsibilities for the careers of the RAF’s aircrew.

Furner joined his brother’s firm, Harlequin Wallcoverings, as general manager for five years before finally retiring. A man of great energy, commitment and service, he considered the last 20 years of his life as some of the busiest. He was chairman of the Aries Association for specialist navigators, and administered the block of apartments in Eastbourne where he lived for many years. He was an active president of the Eastbourne Sinfonia and, with his wife, was a regular attender at Foyles’s literary luncheons.

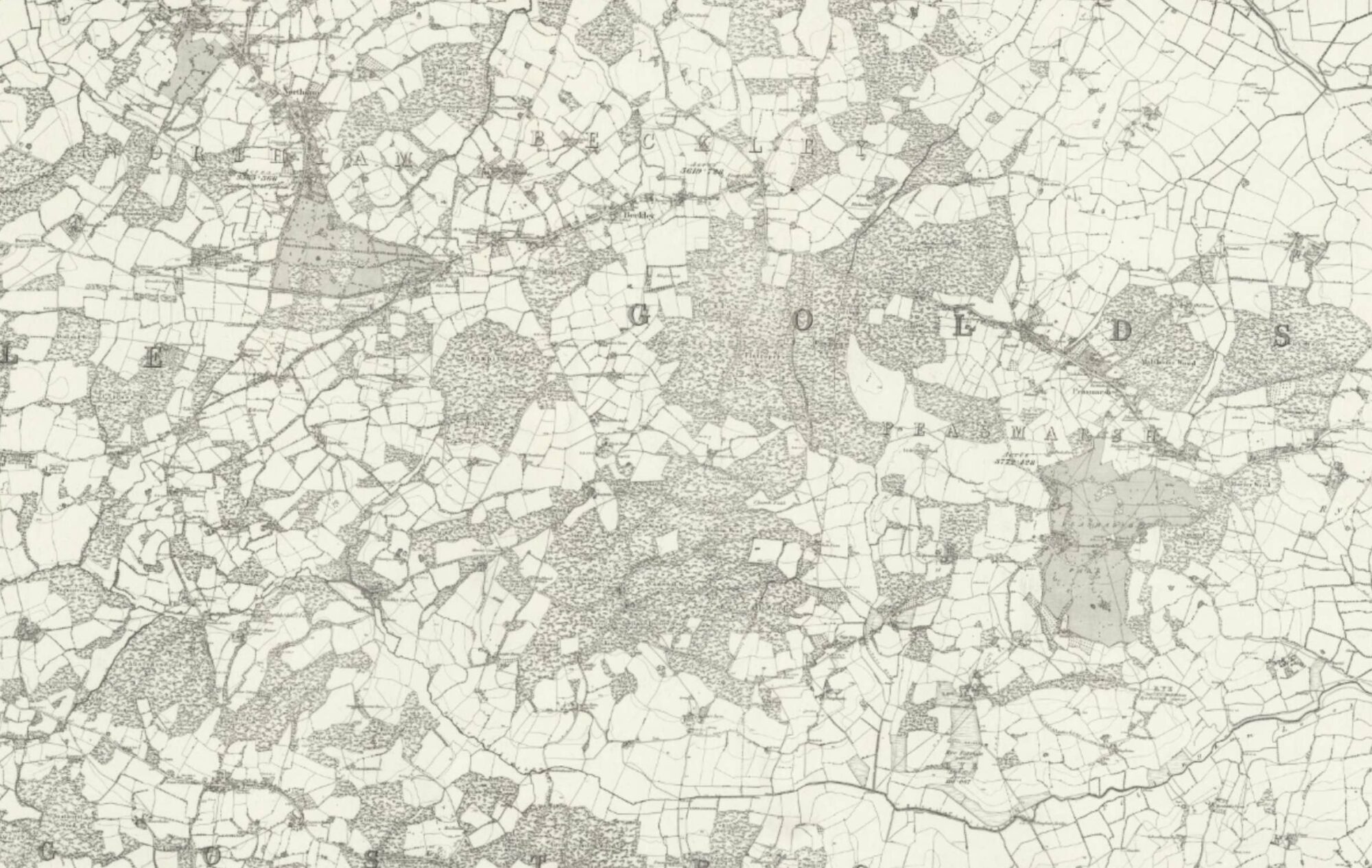

In 1997 the Furners moved to Cromer, where they had met in 1944 when he was serving at nearby RAF Oulton. He became a stalwart of the Cromer Society and was in great demand to speak on a diverse range of subjects including space, computers, climate change and music.

Furner was elected a member of Mensa in 1989. He owned one of the first computers, and had almost completed his autobiography when he died on New Year’s Day.

Jack Furner was appointed OBE in 1959 and CBE in 1973.

He married, in 1948, Patricia Donnelly, who survives him with their three sons.

Table of Contents

<<< Previous Chapter

Next Chapter >>>